Comparing vintage Hollywood myth-making with contemporary narratives on Islam.

Let’s start with a little quiz for the analysts of jihad and radicalisation among our select readership. Where is this quotation taken from?

The Prophet has commanded us to rule the world! Where in all your lands of Spain there is the glory of Allah? When they speak of you they speak of poets, music makers, doctors, scientists. Where are your warriors! You dare call yourself sons of the Prophet?! You have become women! Burn your books, make warriors of your poets, let your doctors invent new poisons for our heroes, let your scientists invent new war machines… and then, kill, burn!

Well, by now you may have guessed that it isn’t from some Islamic State or Al Qa’eda propaganda material. It is the opening scene of a Hollywood production from 1961, El Cid, by Anthony Mann, starring Charlton Heston in the lead role and Sophia Loren as the Cid’s fiancée / sworn enemy / devoted wife, in sequence. With this thundering speech the screen rendition of “Ben” (Ibn) Yousuf, Emir of the Almoravids, tries to raise the fighting spirit of the relaxed Amirs of the taifas of Andalusia. These are the political units that resulted from the dissolution of the Caliphate of Cordoba in 1031, most of whom were already paying tribute (paria) to the Christian kings of Leon and Castilla, Aragon, and the counts of Catalonia.

The speech goes on touching gruesome chords that sound eerily familiar:

Infidels live on your frontiers, encourage them to kill each other, and when they are weak and thorn I will sweep up from Africa and as the empire of the one God, the true God Allah – Allah is the one God – will spread, first across Spain, then across Europe, then the whole world!

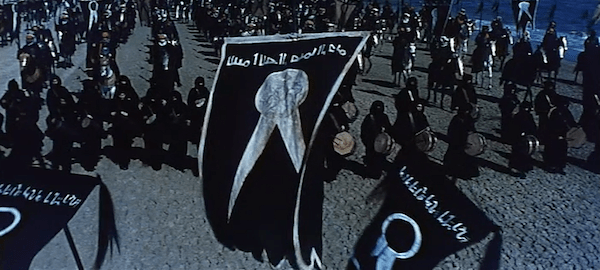

Watching this movie half a century after its release it gives an unmistakable sensation of deja-vou. The representations of yesterday’s movie villains, the black-clad, fanatical hordes ready to “sweep up from Africa” and conquer “first Spain, then Europe and the whole world” have an uncanny similarity with today’s arch-villains, the ISIS terrorists. Even their banners look alike, although it seems that the movie producers thought best of avoiding the exact reproduction of the Muslim profession of faith that is inscribed on ISIS black flags (and on Saudi Arabia’s, on green background) on ‘Ben’ Yousef’s fictional banners, contenting themselves with some arabic looking script sufficiently evocative for the Western audiences.

The most interesting paradox of this game of mirrors is that probably many jihadists today, from the rank-and-file up to the self-proclaimed Caliph, would subscribe to the fictional ‘Ben’ Yousef’s ‘manifesto’ as quoted from the movie, verbatim. Fred Halliday perceptively described this phenomenon in his collection of essays on ‘Islam and the myth of confrontation.’1 He observed how certain ‘Islamic fundamentalists’ explicitly agree with the views held about them by certain right-wing, reactionary ‘anti-Muslimist’ groups (at the time of his writing he was spared by the ubiquitous popularity of the term ‘Islamophobia’), and vice-versa.

The opponents and proponents of the Islamic movement were in agreement that ‘Islam’ itself was a total, unchanging, system, that its precepts operated over centuries, in all kinds of societies, and determined the attitudes of diverse peoples towards politics, sexuality and society. Both sides shared the view of a historically determined, essential ‘Islam’, which is supposedly able to account for all that Muslims say, do, and should say and should do. Khomeini, Turabi, and the Muslim Brothers and the rest are as insistent on this score as any anti-Islamic bigot in the West. Whatever else, the image of a timeless ‘Islam’ is not just the fabrication of fevered Western minds.

— (Halliday, 1996, p. 111)

This generously funded, spectacularly anachronistic epic, gorgeously filmed in 70mm technicolor, pumps orientalism galore. The depiction of the Almoravids as blood-thirsty fanatics will irk some viewers, not to speak of even half-baked historians. But once you (re)watch it in 2016, your immediate comparative landscape has to inevitably take into account also this:

Compared with the offerings of 2016 US electoral campaign and many others on this side of the pond, this Hollywood epic reminds us of Halliday’s insights, and in some ways it goes beyond the game of mirrors. There are some aspects of Hollywood’s El Cid story that throw a modicum of sand in the well oiled mechanism of the ‘myth of confrontation’ between Islam and the West.

First of all it is interesting that the greatest hero of the Spanish reconquista narrative, born Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar, a castle near Burgos in the Old Castilla, ‘entered the pages of legend’ (the last line of the movie) with an Arab name, El Cid, most probably from the Arabic Al-Sidi, Sir or Master. In fact, El Cid did a good part of his fighting – in history and movie alike – side-by-side with Moorish allies, especially the Amir of the taifa of Saragossa, or even at their direct service, acting as a rather independent military operator, or warlord, if you wish. He had a testy relationship with the king Alfonso VI of Castile, a ruthless despot who at some point exiled him and kidnapped his wife and children. In one specific incident, recalled in the movie, El Cid did not join ranks with the Castilla and Aragon combined armies when they were wiped out by the Almoravid expedition force in Sagrajas (1086). After the disaster, the king Alfonso VI thought better of getting round his deep dislike of El Cid’s ‘infidel’ friendships and unorthodox alliances.

Or perhaps is it just a reiteration of the eternal liberal trope where the ‘good’, ‘moderate’ X (substitute with: native Americans, Mexicans, Muslims, etc.) are fighting on the US/West’s side against the ‘bad’ ones? Unfortunately, we live in a time of sweeping amalgames bred out of identitarian intoxications that are utterly functional to the ISIS strategic goal of presenting itself as the ‘champion’ of all Muslims. If watching El Cid in full Moorish garb, riding gallantly into battle side by side with the brave and noble Amir of Saragossa, with all its tawdry bling, feels refreshing it is perhaps a sign of the times.

References

Halliday, Fred. 1996. Islam and the Myth of Confrontation: Religion and Politics in the Middle East. London ; New York: I.B. Tauris.

Acknowledgements

Still images taken from the El Cid movie.