From maras to pandillas, between street gangs and organised crime: a comparative look across the region.

While conducting field research in Central America on women and gangs, I was also confronted with the differences (and similarities) between gangs within the region. Whereas the literature previously made a distinction between the so-called (inter)nationally organised maras and the more locally grown street gangs or pandillas (Cruz, 2010; Rodgers, Muggah & Stevenson, 2009), the gangs as well as the gang discourse have evolved.

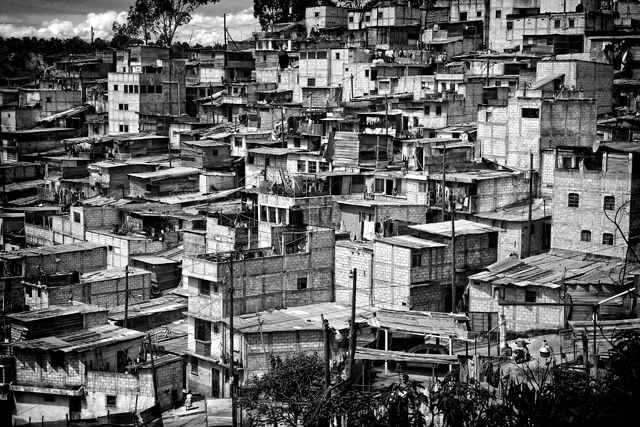

The widespread presence of gangs in Central America is often linked to the casualties of a post-conflict situation. Central America’s so-called Northern Triangle countries (El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras) suffer the most from gang related violence at the hands of the notorious Mara Salvatrucha (MS13) and Barrio 18 or Eighteenth Street gang (B18). Neighbouring Nicaragua, on the other hand, is often portrayed as ‘an oasis of peace’, being the poorest yet safest country of Central America. However, the image is much more complex. To start with, gangs in Honduras cannot be attributed to a post-conflict setting, because there wasn't an open civil war in the past decades. And although MS13 or B18 are not on the rampage in Nicaragua, the country is still part of the drug corridor towards the US, and subsequently cannot escape the presence of drug cartels. In this blog post I want to discuss the differences (and similarities) between gangs in Central America. The analysis is based on a three month field research in these countries, including more than 30 interviews with experts in the field. Before going into detail, I will first set the scene by briefly explaining the recent history of conflicts in the region, and the subsequent ‘emergence’ of gangs.

Gangs in Central America: a history of violence?

From the 1960s till the 1990s, El Salvador and Guatemala went through civil wars, which included genocides and forced many people to flee for their lives seeking refuge within the region or to the North (United States). In Nicaragua, on the other hand, during the Contras aggression that followed the overthrow of Somoza by the Sandinistas, people fled mainly towards Costa Rica because of its geographical proximity. Honduras, being the outlier, was not at war during this period, but served as a ‘neutral’ base for the United States, from where they launched their endless ‘anti-communist’ operations in the region. Even today there are several US-led military bases in Honduras. Then, in the 1990s, when the civil wars and uprisings/revolutions came to an end, the US deployed a massive deportation campaign, sending Central American migrants back to their countries of origin (although many children and youngsters were either born or grew up in the US and barely spoke Spanish).

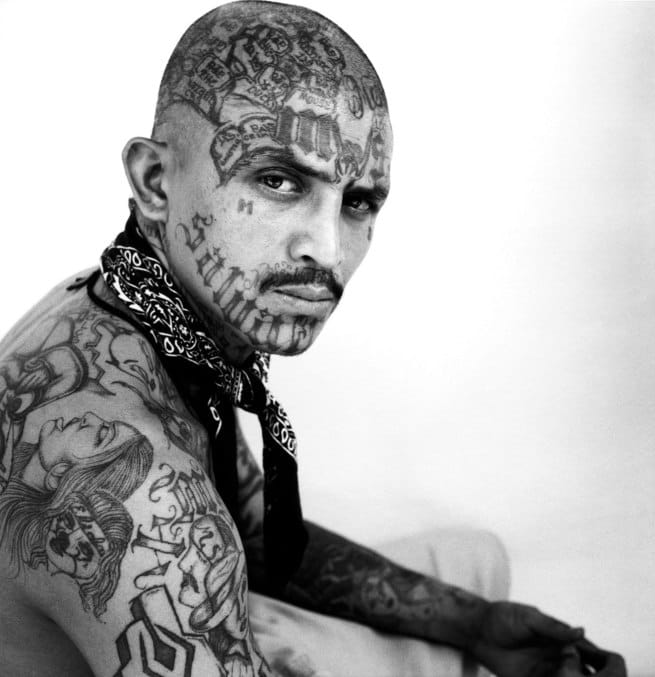

Although you might want to assume that this is when the gangs started to flourish, in post-conflict countries destroyed by war and with lack of employment, Central America’s gang history started much earlier. In fact, the MS13 and B18 have their roots in streets of Los Angeles, California (incidentally, in the same country that currently labels them as terrorist groups). The MS13 was formed by, mainly, Salvadoran migrants who felt the need to unite against the B18, which had links with Mexican criminal groups. When the gangsters were deported to Central America, they found some territorial urban street gangs (as we can find in many urban cities) and transferred their practices and codes, including the use of firearms and tattoos, to them.

Nicaragua and the Northern Triangle: coldblooded crime versus an oasis of peace?

It is not the first time that Nicaragua is labelled as “Central America’s security exception” (Schrader, 2017, p. 360). Also one of the experts I interviewed stated that the difference between Nicaragua and the NorthernTriangle “is a question of passing the border and finding yourself in a country full of birds and going to a country full of violence” (personal communication, May 9, 2017).

But how, then, can the differences regarding gangs in Nicaragua and the Northern Triangle be explained? Several aspects are involved. First of all, according to some experts I interviewed, the nature of the conflicts in the Northern Triangle and Nicaragua were very different and thus had a different impact on the society. Nicaragua went through a genuine revolution, which included the reform of the security system. Also, Nicaragua did not have to deal with incoming gang members from the US, like the Northern Triangle, and they strictly controlled their borders (even today). In addition to that, they invest more in community policing and this, subsequently, is supposed to increase the bonds between the police and civilians. In the Northern Triangle, on the other hand, gangs and organised crime are often strongly intertwined with governmental institutions, and citizens have no trust in the police and military, who allegedly should protect them. To give an example, if a citizen calls the police to report drug dealers who are operating in his neighbourhood, it is more likely that the drug dealers knock at his door to give him 24h to leave the neighbourhood (or country, for that matter), than the police would actually investigate the case. I guess the high levels of impunity should not be so surprising then.

Also, If we take a look at the structure of the gangs, we notice differences as well as similarities. To start with, notwithstanding the media often interchangeable use the words mara and pandilla, the concepts do have different meanings. The MS13 probably even coined the term mara back in their Los Angeles days, while B18 appropriated the generic word pandilla its own, also to differentiate themselves from the rivals. Hence, a MS13 member feels insulted when you call him a pandillero, and likewise B18 members will by all means avoid the number 13 just as they claim the term pandilla. Furthermore, while the MS13 (with largest presence in El Salvador) and the B18 (more prevalent in Honduras) are the most notorious, there are many other, although smaller, gangs present in Central America. In Honduras, for example, youngsters who deserted from one of the bigger gangs, or do not want to be recruited by them, started forming their own groups, like the Benjamins, Chirizos or Quinceañeros. In El Salvador, the B18 split up into the Revolucionarios and Sureños factions.

What about the different positions within the gangs? Although the terminology might slightly differ from country to country and from gang to gang, at the lowest ranks you have banderas, which are (mostly) kids sitting on street corners and reporting to the gang who enters and who leaves. The traquetos are used as hitmen, and also the paisas belong to the lower levels of the gang. Girlfriends of gang members are called jainas, but women with more reputation can become hongras and take the other women under their guidance. Then there are the mareros or pandilleros, who are under the command of a homie (homeboy) of a local clica. These clicas are in turn under the command of the bigger leaders, who often serve long prison sentences.

Finally, there is a slight division in labour between the different gangs. While the B18 dedicates itself more to extorting small and medium-sized enterprises and citizens (the so-called renta in El Salvador, impuesto de guerra in Honduras and extorsión in Guatemala), the MS13 focuses more on drug trafficking.

From youth street gangs to organised crime… and back?

So the gangs in Central America have evolved from street gangs in the 1990s to organised crime in the 2010s, especially the MS13 (see for example Salguero, 2016); but I would argue that there might be a further evolution back to more fragmented street gangs due to the mass incarceration of gang leaders in maximum security prisons.

As from the so-called 'Tough hand' law-enforcing operations in the mid-2000s (Mano Dura in El Salvador, 2003; Plan Super Mano Dura in El Salvador, 2004; Operación Libertad in Honduras; Plan Escoba in Guatemala), gang members were incarcerated on a large scale. Nevertheless, the leaders continued to command from behind the bars, and gang related crime and violence did not decrease. The gangs adapted to the so-called ‘Anti-Gang’ laws, by no longer tattooing themselves visibly and wearing less baggy clothes. Then, in 2012 the gang leaders in El Salvador, who were locked up in highly securitized prisons, negotiated a truce with the government, whereby they promised to lower homicide rates in exchange for more freedom within the prison (including the availability of mobile phones).

Additionally, the power of the gangs rose on many levels, as they even started sending their members to the university to become doctors, lawyers and business executives who could subsequently serve the gang. For this reason, the MS13 is now by many seen as a form of organised crime, rather than a street gang. However, the truce in El Salvador failed after a year and the security measures raised again. Also in Honduras the gang leaders have more recently been sent to two maximum security prisons that were nicknamed El Pozo (‘The Well’) and La Tolva (‘The Hopper’). I wonder how this will affect the future of the gangs’ structure and power. Will the mass incarceration of gang leaders actually break the gangs’ cohesion or will it lead to the recruitment of more members as suggested by one of the experts I interviewed?

References

Cruz, J.M. (2010). Central American maras: from youth street gangs to transnational protection rackets. Global Crime, 11(4), 379-398.

Rodgers, D., Muggah, R., & Stevenson, C. (2009). Gangs of Central America: Causes, Costs, and Interventions. Geneva: Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies.

Salguero, J. (2016). ¿Extorsión o apalancamiento operativo? Aproximación a la Economía Pandilleril en El Salvador (Report No. 13/2016). San Salvador: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung FES.

Schrader, S. (2017). Nicaragua: Central America’s security exception. NACLA Report on the Americas, 49(3), 360-365.