The police in Kyrgyzstan needs to be reformed in a fundamental and consequent manner to start functioning according to legal provisions and statutes, and to carry out crucial societal tasks. Until today, this institution has not only often failed to uphold law, order and basic security, but has itself been a source of insecurity. Pilot projects on community policing or patrol police indicate the positive potential of reform, but also illustrate the reluctant and ineffective overall approach of the responsible actors.

What is the potential of civil society involvement in police and security sector reform? Research on these topics has been growing in recent years. Given the deepening tendency towards authoritarian and repressive approaches to public order and security provision, many analysts attribute a critical role to non-state actors in bringing about forms of security that are accountable and adapted to people’s needs. Thus, as both recent conversations framed around ‘local ownership’ and longstanding debates preceding them agree, a reliable, accountable and transparent security sector cannot be created through external intervention and top-down implementation by domestic decision-makers and experts alone.

Beyond this basic consensus, there is little clarity on exactly how and under what conditions civil society actors can effectively and successfully participate in and influence police and security sector reform. As research from African and Central American contexts – viz. Nicaragua – has shown, efforts of reform ‘from below’ may be inherently limited, as civil society platforms often lack the capacity, experience, knowledge and skills that are necessary to leave their mark on reform trajectories. Furthermore, domestic security actors are often not ready to cede ground in negotiation reforms or may even re-appropriate international support to protect and fortify existing power regimes.

A promising avenue to provide further insight into this nexus is to focus on the roles and practices of civil society platforms promoting alternative approaches to law enforcement reform. Focusing on Kyrgyzstan and the particular case of an NGO network called Civic Union “For Reforms and Result”, my research on these aspects has helped unpack the often partial and contingent impact of this actor on police reform in the Kyrgyz Republic. While situated in a very specific context at first sight, this analysis yields insights that corroborate and extend a sizeable body of scholarship on police and security sector reform in former Soviet countries. Trends in this region exhibit, as shown in Erica Marat’s recent book on Politics of Police Reform, important parallels and similarities with other (semi-)peripheral areas across the globe which should inform a more systematic conversation across regions and disciplinary fields. Complementing both the above scholarship and the related bodies of international practice theory and knowledge production analysis in peace, conflict and security studies, this investigation contributes to mapping out three key roles/practices of the police reform network.

The first one is ‘activism’. It captures how the platform established itself in policy debates and decision processes thanks to a country-wide mobilisation of various NGOs and their constituencies. In 2011, activists of the constitutive NGOs organized 32 public hearings all over Kyrgyzstan, which inspired them to scale up efforts to bring about substantial change in police reform programming. The collection of 10,950 signatures in support of an ‘Alternative conception for the reform of law enforcement agencies’, which the activists handed over to parliament and the government, was a clear indicator of the ‘Civic Union’s’ sizeable support base across the country. This weight and the efforts invested paid off in the sense that the activists were invited to consultations with the prime minister and internal affairs officials. These meetings inspired a number of decrees on law enforcement practices and further collaboration. Yet, the activists’ input into the reform process was subject to challenges, negotiations and haggling, which led to the deferral or rejection of some proposals.

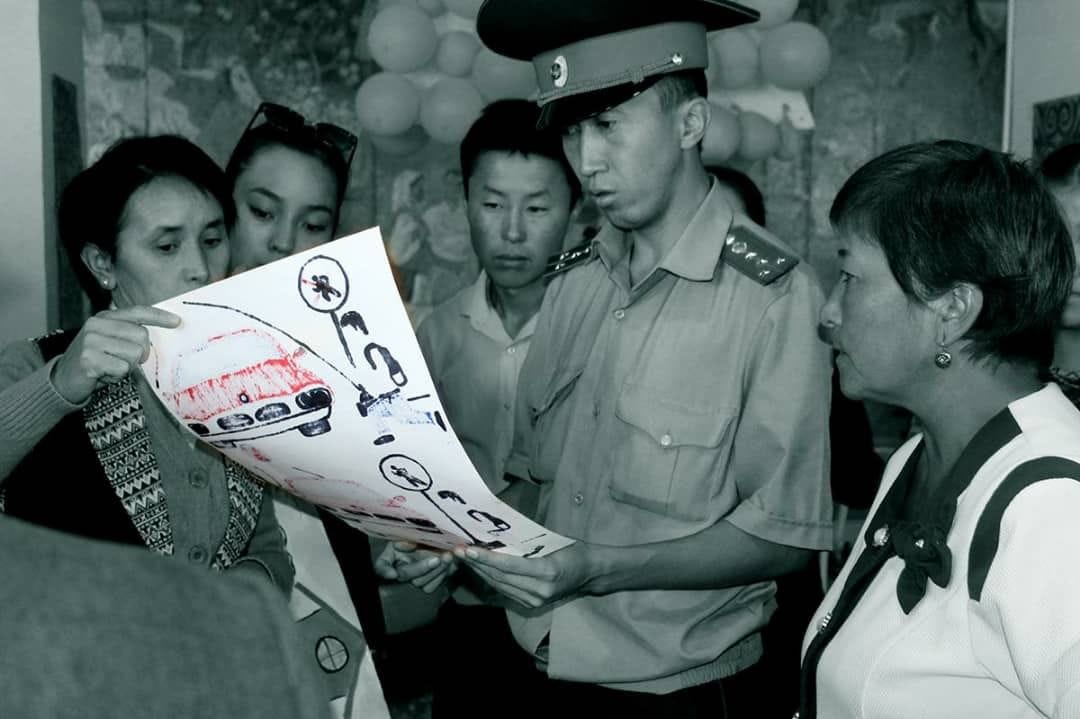

The resistance the activists met made them realize that to have a lasting impact on reform, they also needed to build up and ‘prove’ a degree of ‘expertise’. The dismissal and silent ignoring of their input was often justified with an alleged lack of experience, as almost none of the activists had served in the army or law enforcement organs and given their belonging to a younger generational cohort – molodye liudi or ‘young people’. Therefore, the Civic Union was urged to acquire and demonstrate knowledge and experience in the areas of law enforcement and community security in particular. This practical component was realised in a project on ‘social partnership in public security and crime prevention’ financed by the United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Arguably, the project led to the (re-) activation of so-called Local Crime Prevention Centres (LCPCs, Russian: Obshestvenno-profilakticheskie tsentry) and their constituent civil society and administrative actors. The project’s effects were important in making the latter actors work together with local police to identify and solve security issues like frequent road accidents, school racketeering, or violence among youth. Yet, the levels of cooperation between involved parties and their agility in tackling problems was roughly reproduced, i.e. staying low in less active communities while remaining high or increasing in those already experienced with security initiatives. The more important part for the overall strategy of the Civic Union was then to interpret the overall results so as to back up claims and demands for more cooperative and people-centred approaches in community-level law enforcement, and further, to demonstrate the organisation’s own ‘expertise’ in such questions.

This points to the third role and associated practices of the Civic Union, which is knowledge production. Trine Villumsen Berling has rightly argued that knowledge is a decisive factor in social processes, as agents can ‘mobilize’ it ‘as weapon[s] in political struggles … to secure for themselves the power to impose the legitimate version of the social world’. At the same time, she cautions that, in ‘political practice’ … the ‘lack of knowledge’ rarely hinders governments to take actions in the interest of exerting sovereign control. Knowledge production by civil society activists and ignorance or non-knowledge on the side of power holders turn out to be key ingredients of the observed police reform dynamics as well. As part of wider trajectories of global knowledge transfer and adaptation, the Civic Union coined an approach named ‘Co-Security’ (Russian: ‘SoBezopasnost’) which aims to facilitate the joint [Russian: sovmestnoe] provision of security as discussed in the community-level project above. Under this approach, the platform implemented its projects but also generated a large number of commentaries and analyses. These form a remarkable body of knowledge (which I have analysed in a supplementary appendix) which presents overbearing evidence in favour of more comprehensive law enforcement reforms. Yet, in recent years, each move of the government and ministry officials towards such reform has been followed by retractions. Most tellingly, ex-PM Sapar Isakov, who, using the Civic Union’s terminology, had vowed to support the creation of a ‘modern’ politsiia to replace the Soviet-era militsiia was arrested, indicted and sentenced to a long prison sentence because of a corruption scandal.

Thus, in sum, there is ample evidence of the limits of the Civic Union’s efforts to bring about reform steps against the resistance and political manoeuvring of the political establishment around hardliner president Sooronbai Jeenbekov. Nevertheless, the CU managed to consolidate its role as practice-oriented and knowledge-generating expert who cannot be easily excluded from reform process anymore. The latest achievements testifying to this status are the extension of a pilot project creating a new patrol police unit from the capital Bishkek to the southern city of Osh; the institutionalisation of a parliamentary oversight mechanism created on the Civic Union’s and MPs’ initiative; and a new draft law ‘On the foundations of crime prevention’, which activists hope will further advance effective and needs-based approaches to law enforcement. Drawing on a collaborative and practice-based approach, these findings help elucidate the efforts necessary for civil society to get involved in reform processes and successfully influence them. And perhaps most importantly, they shed light on how partners from international organisations, donors and academic researchers can help such platforms to overcome challenges and resistance in their efforts to shape accountable and transparent security sector institutions.

This research was first carried out as part of my PhD project. Its main results have been published in a recent article, also available in Russian.

Cover photo by by Christopher Herwig, Man wearing a traditional Kyrgyz hat (Kalpak ) walking past a row of police hats. Bishkek, 2004. (C) Pressens Bild https://flic.kr/p/CZuuf