The Republic of Turkey is a relatively young nation state, born from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire. The question of national minorities was among the factors that led to the unraveling of the Empire after its defeat in WWI. The Armenian genocide effectively proved to be an ‘uncomfortable’ antecedent for the political aims proposed by Mustafa Kemal "Atatürk", the Republic's founder and President from 1923 to 1938, who used a modern secular approach to break away from the previous, Islam-based imperial system. In order to build the new state’s identity on historical-cultural foundations, a new nationalist narrative focused on the celebration of positive antecedents, whilst censoring negative ones, such as the deportation of thousands of Armenians and several human rights violations occurred against Greeks, Assyrians, Kurds and other minorities during the final stage of the world conflict. While the former empire’s territory was dotted with a multitude of ethnic groups (including Armenians, Azerbaijani, Kurdish, Cypriots and Greeks), the new government established its policies on Turkish identity, adopting a nationalist secular approach. As a direct result, the denialist stance towards the Armenian genocide took solid roots in the several decades that followed, and still thrives today, resulting in a distortion of the historical truth, therefore posing the risk of repeating similar violence.

Turkey’s ‘formative years’ play an essential part in the development of its current set-up. The imposition of the one-party system (1923-1945) and the entry into force of Turkish Penal Code’s Article 301 (in 2005, last amended in 2008 within the framework of the Council of European Union priorities for the Access Partnership with the Republic of Turkey), which punishes public offences against the Turkish nation, have effectively limited freedom of expression, civil and political freedoms, de facto hindering the development of a concrete and constructive opposition. Regarding the Armenian question, several journalists, publishers and intellectuals, such as Taner Akcam, Hrant Drink, Hasan Cemal, Elif Safik and many others faced trials under Art. 301. For example, famous novelist Orhan Pamuk was accused after stating that “One million Armenians and 30,000 Kurds were killed in these lands” in an interview for a Swiss Magazine. Nevertheless, structured and cohesive movements began to develop within Turkish civil society since Prime Minister Turgut Özal’s government (1983-1989), committing to the promotion of freedom of expression and thought, as well as the protection of minority rights – specifically through humanitarian activities. In the 2000s, these association further expanded – reasons for this can be found in the process of openness and integration towards the European Union, as well as Turkey’s economic growth, brought about by AKP’s new economic measures and the increased economic partnership with Europe.

These social and cultural developments played a key role in the bilateral relations between Armenia and Turkey. In fact, while their relationship has been cautious and ambiguous at both political and institutional level, some bottom-up initiatives have emerged at the social one. Specifically, in opposition to Turkey’s denialist stance, several sections of Turkish civil society have taken sides against official political positions. Especially in the occasion of the 24th commemoration day, were organised different initiatives in these years, such as in 2012 a musical called “A rainy day in April” to mourn the victims of the Armenian genocide. In universities, conferences and events regarding the Armenian question were held: in 2005, Murat Belge, a Turkish intellectual, organised a conference on the debate surrounding the genocide at Istanbul Bilgi University. In 2014, the School of Political Studies of Ankara University hosted the conference “Sealed Gate: Prospects of the Turkey-Armenia Border”, which saw the participation of some Turkish MPs. Indeed, civil society involvement culminated in 2007, when Hrant Dink, a Turkish journalist and political activist of Armenian origins, was assassinated by a Turkish nationalist. The act was strongly condemned by a section of Turkish society, which joined the cry “we are all Hrant Dink” during the journalist’s funeral. In 2008, a group of about 200 Turkish intellectuals, journalists and academics published a public apology for the victims of the Armenian genocide, through which they declared: “I empathise with the feelings and pain of my Armenian brothers. I apologise to them”. This stance was supplemented by the increase of more progressive and liberal groups – especially those focusing on the lack of historical-cultural transparency and political corruption – which still struggle under the government’s oppressive policies.

Over the years, attempts have been made to recognise and discuss the genocide, though it remains a rather sensitive and uncomfortable issue for civil society. Activities have developed around workshop and conference programs, in line with the greater commitment of both Armenian and Turkish academic worlds to the cause. At times, initiatives are further supplemented by experiences “in the field”, exchange trips, cultural visits between volunteers of the two neighbouring societies, all organised and promoted by private and non-governmental institutions – as Armenia and Turkey still do not have contacts at the diplomatic level. The unresolved issue of the Armenian question lies in the different conception of the 1915 events – ignored by the Turkish government, recognised as genocide by the Armenian community. Therefore, civil society projects, such as those by the Hrant Dink Foundation, focus their efforts on fostering confrontation and dialogue between the different testimonies and identity perceptions. The cultural component and the shared historical heritage uniting the two countries represent the focus of relations between the two communities, engaged and involved in the promotion of monuments, buildings and churches. For this reason, several associations campaign to promote historical sites and establish memorials, adopting an approach that goes hand in hand with the right to memory and recognition of the historical past. Their valorisation also has a strong effect on cultural identity: materially representing a certain event forces all parties involved to face the past and confront it.

Most NGOs and associations – such as Anadolu Kültür, Toplum Gönüllüleri, the Hrant Dink Foundation, the Heinrich Böll Foundation, the International Centre for Human Development and the Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation – working to uncover historical truth and Armenian-Turkish reconciliation are supported by European and US institutions and foundations linked to the diaspora, further proving that the genocide issue is still very much felt among these expat communities. While domestic civil societies are largely embedded in a polarised context, diaspora communities have been implementing cooperation projects, enhancing and conserving cultural heritage in both countries. Indeed, while it is true that recent years have seen an increase in Turkish civil society’s liberal and democratic initiatives, they have had to clash with Erdogan and the AKP party’s “iron fist” approach, developed from the failed attempt at a coup d’état in 2016. As a result, their activism received a setback, due to the government’s increasing oppression against any form of opposition. In fact, this approach hinders civil society’s objectives, containing activism through repressive selection, and seeking to build an alternative civil society. This resulted in a strong polarisation between the most liberal and progressive groups and more nationalist and populist factions; such dichotomy, combined with an increasingly unstable economic, political and social context, contributes to fragmented and weak responses by civil society organisations.

The role and work of civil society ensure political opposition. Civil society is necessary to guarantee the protection of fundamental freedoms of expression and thought, which are severely threatened by Erdogan’s oppressive policies. Their stance towards the Armenian cause and other minority groups’ unresolved issues gives Turkey a chance to deal with its bias based on a particular identity, entrenched in censorship and penalties. Indeed, genocide denialism strongly impacted both Armenian and Turkish stances, worsening their social and diplomatic ties; it still causes a dangerous identity gap amongst the Turkish society, consequently affecting its relationship with all other cultural and ethnic groups living in the country – especially the Armenians. Genocide denialism remains a controversial topic, likely to cultivate anger and revenge within those groups who claim more social integration and equality, as they feel oppressed by Erdogan’s national and identity policies.

Even if the historical conflict between Armenia and Turkey still affects political dynamics in South Caucasus, new initiatives and dialogue-based programs are spreading at the social level, especially among young generations and the academic world. The GPoT Center is a Turkish no-profit organisation aiming at reconciling Turkish and Armenian people that is engaged in several projects, in which young students and journalists participate, as “Support to Armenia–Turkey Rapprochement (SATR), Program in Dialogue-Building between Turkey and Armenia, Days Two and Three in Armenia-Turkey Rapprochement, Mutual Bias and Objectivity in the Media of Armenia and Turkey” projects. In the last years, an increase of civil society movements in both countries has shown a possible path to their rapprochement, signalling the demand for recognition of past events. Cultural and dialogue-based projects testify to the shared will to overcome past conflicts and develop a new culture of tolerance and coexistence in the region. In accordance to the media and cultural engagement on this matter, the Caucasus Centre for Peace Making organised the 2010 Turkish Film Festival, screening 7 Turkish works in one of the main cinema of Yerevan, paving the way for the future Turkish-Armenian collaboration in the annual Golden Apricot Film Festival. Today, bottom-up initiatives face the challenge of shifting their demands at the governmental level, bringing the Armenian question into the educational and cultural national policies. To reach an effective impact and involvement of the Turkish and Armenians into the Genocide question and an eventual rapprochement, it is necessary to encourage an effort at the diplomatic and political level, fostering and implementing educational and cultural programs on the Armenian question and on the historical factors happened during the period of Ottoman Empire, in order to sustain and promote more awareness and knowledge of the shared past. In the context of the reconciliation process, civil society groups have been and continue to be a key driver – not only for the recognition of the Armenian genocide, but also for the promotion of historical truth and cultural heritage, too long hidden and silenced.

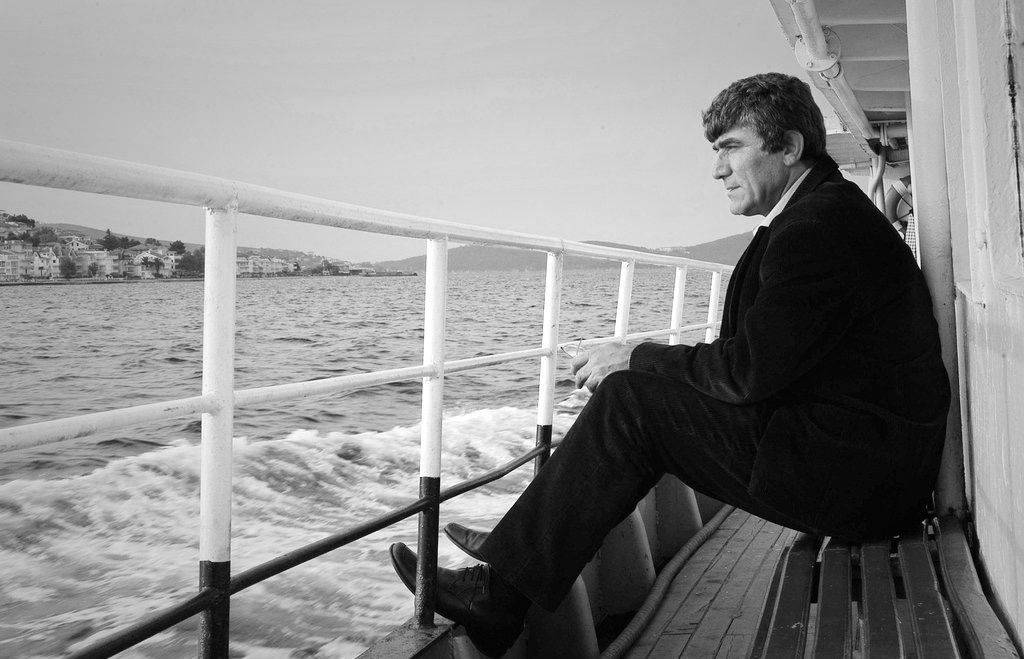

Cover photo: Hrant Dink, (C) WDR/Tempo Istanbul