Alongside the military intervention in Syria and the outbreak of renewed hostilities with the PKK, Turkey has also focused its foreign policy ambitions on Libya and the eastern Mediterranean. These developments were tackled during the second part of the conference “Turkey’s Foreign Policy: Continuity and Change”, organised by the Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies on December 9th, 2020. Indeed, in these strategic areas, Ankara has carried out controversial interventions as part of the hard power policy of the AKP-MHP nationalist alliance.

[read the first part of this report]

TURKEY AND LIBYA

Turkish “endgame” in Libya represents another example of the new Islamist/nationalist reconfiguration of Turkish foreign policy. While the relationship between Turkey and Libya has deep historical roots since the Ottoman Empire, one can identify three phases characterising Turkey’s role in Libya after the fall of the Gaddafi regime, as explained by Luca Raineri – researcher in Security Studies and International Relations at the Sant’Anna School. The first phase started in 2011 when Turkey gained considerable popularity among the Arab Spring revolutionaries, including in Libya. This is the period when Turkey was presented by many international actors (such as the USA and the EU) as a model for the Middle East and the broader Muslim world thanks to its alleged achievements in economic development, religious moderation, and democratisation. Nevertheless, compared to the central engagement of Qatar and the UAE, Ankara actually played a marginal role in the Libyan revolutionary events. Unlike in Egypt or Tunisia, the 2012 democratic elections in Libya were not won by a party linked to the Muslim Brotherhood. In the second phase, Turkey became a meeting point for Libyan Islamist factions who were marginalized in the country, including members of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group and the National Salvation Government. The failure of political Islamism in the region led to the militarization of Turkish regional policy, while the alliance with nationalist parties at home increased the emphasis on the assertion of sovereignty rights, including through the implementation of the navy power: the Blue Homeland Doctrine was born. These changes paved the way to the third phase. Starting in April 2019, Khalifa Haftar’s attack on Tripoli would have probably been successful (causing the GNA – Government of National Accord – collapse) if Turkey had not intervened by offering military cooperation to the GNA. Left with no options, the GNA accepted to sign two memorandums of understanding with Turkey, one on military cooperation and one on the redrawing of the sovereign claims over the continental shelf in the East Mediterranean. As Turkey overtly scaled up its military support to Tripoli, the GNA survived by pushing back Haftar’s attack. As of today, Turkey has become a dominant actor in Western Libya, posturing as the main protector of the GNA against the aggression of Haftar and its foreign allies: Egypt, the UAE, and most notably Russia.

COMPETITION IN THE EAST-MED: NEW AND OLD ENEMIES

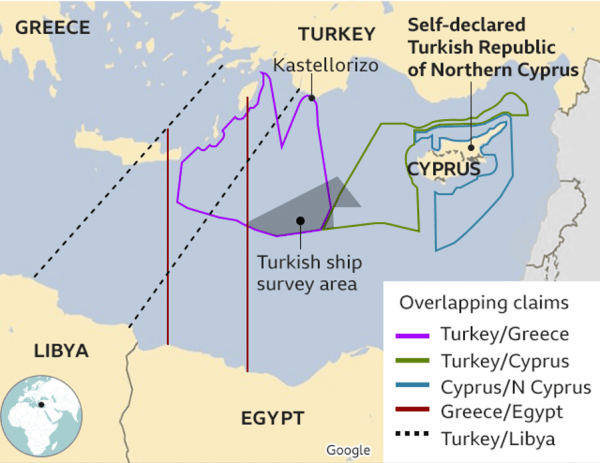

As part of the Blue Homeland doctrine and of the renewed cooperation with Libya, in November 2019 Turkey and Libya signed a Maritime Boundary Treaty aimed at reshaping the respective Exclusive Economic Zones in the Mediterranean Sea, granting rights over ocean bed resources. Unsurprisingly, the deal has aroused the discontent of Cyprus, Egypt, and Greece. This represents just one of the events that led to the formation of what Lea Nocera – researcher in Turkish language and literature at the University of Naples L’Orientale – has defined as an “Anti-Turkey front”, a strategic alliance between, Cyprus, Greece, Israel and Egypt on military and energy cooperation. As a matter of fact, in January 2020, Greece, Israel, and Cyprus signed the EastMed gas pipeline deal (for the construction of a natural gas pipeline, which would connect East Mediterranean energy resources to Greece via Cyprus and Crete). Further, in August 2020, Egypt and Greece signed an agreement for the establishment of an Exclusive Economic Zone between the two countries. In the meantime, Turkey’ relation with Israel is further strained by Ankara's ongoing support for Hamas, as stated by Arturo Marzano – professor of Asian History and Institutions at the University of Pisa. Undoubtedly, the tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean region are a longstanding issue. Nonetheless, as argued by Harry Tzimitras – Director of the PRIO Cyprus Centre – one is left with the impression that Turkey has not tried to manage these issues but to fuel tensions.

As a matter of fact, on different occasions, President Erdoğan has clearly stated his ambition of making Turkey a leading country in the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and North Africa region. This aggressive posture, as Lea Nocera has argued, has shown Turkey’s capacity, or at least intention, to regain the central stage of the international arena, from the corner where it was left by the failure of the “zero problems” policy and soft-power approach. Nevertheless, tensions with Greece and Cyprus on maritime borders after the Turkey-Libya EEZ agreement are inevitably increasing, while the relations with Egypt and Israel remain controversial. Despite its foreign policy ambitions, Turkey has found itself increasingly isolated regionally, due to its involvement in disputes with many neighbouring countries and traditional security partners.

Cover photo from Athens Magazine