Old and new Somali migrations flows to Europe, between voluntary and forced relocation.

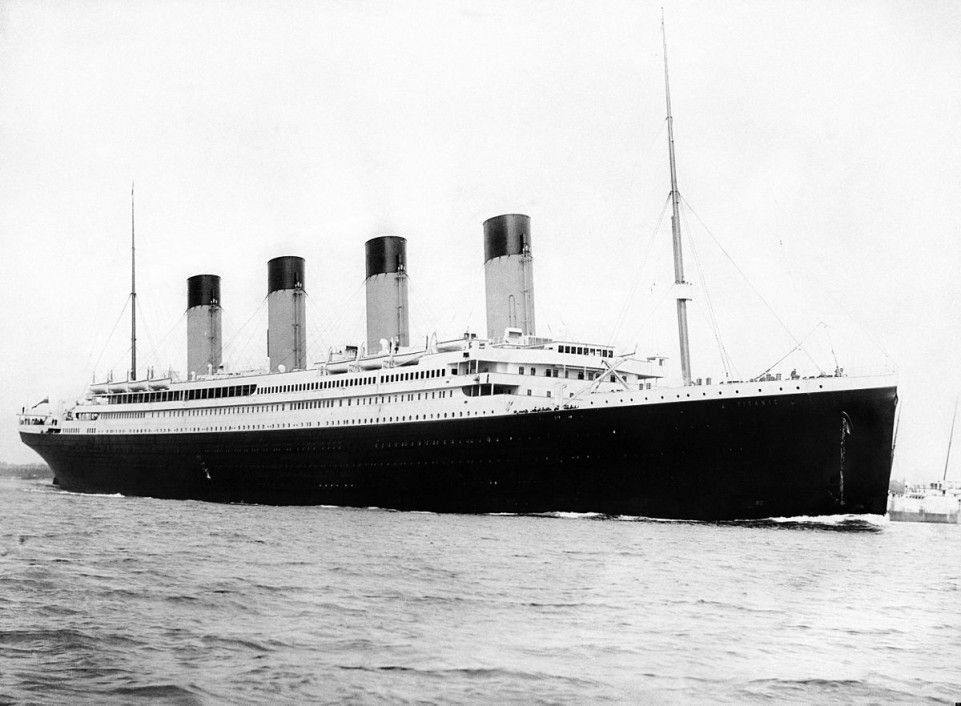

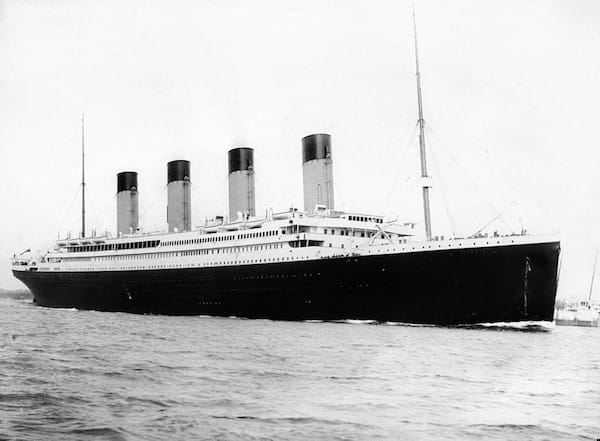

Drawing from field work at the local Somali community based in Florence (Italy), in this post I discuss old and new diasporic flows on the background of the on-going European ‘migration crisis’. While the appellations Vecchie Lire and Titanic exemplify distinctive migratory patterns, they also signal a dramatic change in local and global migration determinants. Within this new scenario the legal framework still in force in Europe proves quite inadequate. I argue that the difference between forced and voluntary migration is ill-defined: the ‘space’ in-between is the question to be addressed.

“Our promise is to immigrate abroad”. These words are graffitied on a corridor’s wall at the local Farah Omar School in Hargeysa, Somaliland. Behind the corner, in the courtyard outside, a teacher addresses an assembly of youngster standing right in front of him. It is 8:00 o’clock in the morning, and they are just about going to class, when he preaches “I am urging you, do not leave for foreign lands, I ask God to give you riches right here”. Many leave though, it is what they call Somalia’s lost generation.[1]

And they are not just youngsters. Many Somalis hope for a better future in Europe. Some of them are still in school age, others full-time unemployed, or women casual workers.[2] Some others come from rural contexts, and they know how to milk a camel, although they conceal it behind their smart phones. Despite the many attempts at curbing the phenomenon, they embark on a migratory path – the Somalis call it Tahriib – along a perilous itinerary that often leads them from Hargeisa to Addis Ababa, Khartoum, Cufra, Tripoli, Lampedusa, and up north, as north as possible, in the heart of Fortress Europe. They are part of the surge of arrivals that these very days are under the spotlight of every goodhearted media outlet or sensitised politician.

It has been estimated that from Somaliland only about 300 youths leave every month.[3] In South-Central Somalia and Puntland figures are for sure more substantial. Many leave from Mogadishu, or at least they ‘have’ to say so, in any case from the rest of the country, often escaping violence and emptiness, combined in various degrees. There are no perspectives in Somalia, they say, no jobs, no education, no chances whatsoever. As John Berger put it some 40 years ago “through their own individual effort they try to achieve the dynamism that is lacking in the situation into which they were born” and “those with the most initiative do the one thing which seems to offer hope: they leave”.[4]

Do they qualify as asylum seekers? Actually many of them are considered ‘just’ economic migrants, as distinguished from the so called forced migrants. These categories are particularly in vague these days, while adopting a strict legal perspective. Somali newcomers mostly first set foot in Europe at an Italian shore, irregularly, undocumented. According to the current policy they are immediately ‘invited’ to apply as asylum seeker, albeit the designated Territorial Commission will take quite some time to process their case, while chances of being successful are often scarce.[5] Long gone are the days when migration to Italy from Somalia was an elite affair, the intelligentsia of the country relocating to safe Italy, away from dictatorial purges or clan struggles. Back then – before 1991 – it was quite easy to be granted a visa, a residence permit, applications were limited.[6] Today the scenario is completely different. Somaliland is actually enjoying a period of peace and moderate security lasting from 1991, while here and there in South Central Somalia the Federal Government still struggles, assisted by AMISOM, with Al-Shabaab. In principle, however, the civil war is over, and current regional contentious rarely result into armed confrontations. Nevertheless, Somalia is plagued by many others less palpable and documentable issues, which deeply affect observable opportunities and imagined aspirations, while shaping the profile of would-be migrants.

Old and the new Somalis in Italy, are well apart, religiously and culturally. Backgrounds can be so different that often prevent them from communicating with each other. Two key words alternatively promote or stigmatize their exclusive belongingness. The late comers are called Titanic, an obvious reference to the way they have reached Italy, the term echoing the expression “boat people”.[7] The old guards are called Vecchie Lire instead, the old national currency in use in Italy. They came by plane, they settled down or studied in Italy long ago, they can speak Italian. Most of them have a residence permit, if not the Italian citizenship. Titanics came by boat by contrast, and usually they do not want neither to make their living nor to remain in Italy. Apparently they feel barely attached to a country whose colonial involvement in Somalia is just a remote oral account. Italy to them is rather a geographical accident on their run away from the Horn of Africa. They seek for a way to reach other countries in Europe, Sweden, Belgium, Finland, and above all, in the last year or two, Germany. Here social benefits are much more generous, and life easier, they think.

But access to destinations is regulated by pass-words. And the pass-word among them, and ironically enough not just at European summit level, is Dublin. Titanics are divided between Dubliners and non-Dubliners. As soon as they reach Europe, if they are taken their fingerprints – during the so called photo marking procedure – they irreversibly fall within the scope of the Dublin Regulation. They can only hope, if they want to stay, to be granted some form of international protection. Hence, their application pending, they have to remain within the territory of the state where they first touched the European soil, while their fingerprints record is filed in the Eurodac system. The idea behind it is to prevent them from asylum shopping, as it is technically defined, or from remaining in orbit for years. However, some of them do not want to wait this time in Italy, it is like enforced idleness to them, and they push their luck by leaving anyway. Others, in a act of desperation, even burn their fingers, in the belief to destroy any evidence.

What are Titanics actually looking for? A residence permit, any piece of paper that would allow them to remain legally in Europe. If they do not qualify as refugees, they might be entitled to the subsidiary protection, or the humanitarian protection, maybe.[8] However, it is very unlikely for them to be in a position to migrate legally to their preferred destination, based on professional migration quotas. Too complicated, too distant. The tertium non datur they are tempted by informal, instantaneous, and more emotional exit strategies, which often aliment the so called “migration industry”.[9] Once they reach Europe though, they are addressed with mismatching tools and provisions that prove more and more inadequate today. It is like forcing a new scenario into an obsolete legal framework, which was designed under different circumstances or meant to serve a well defined political outlook. Basically, the Geneva Convention (1951), the Dublin Regulation (No. 604/2013), and the recently released EU Agenda on Migration (May 2015) are all centred in the distinction between forced and voluntary migrants. This is the cornerstone of the EU and the Member States policy, whose main worry is to not mix up the different legal entitlements these classifications give access to. Yet, as Castles et al. put it “voluntary migrants also face constraints…” while “many forced migrants do have a certain level of agency”.[10] In other words there is an expanding blurred zone, at the intersection between these two extremes, and it has nothing to do with the comfortable categories we are accustomed to.

Migration processes are affected by macro (labour markets, inequality, wars, conflicts, interstate relationship, migration policies, etc.), meso (migrant networks, social capital, transnationalism, etc.) and micro factors (individual agency, social remittances, etc.) at the same time.[11] Their interplay and resulting outputs are ingrained in the current level of technological development, capitalism penetration, and diffusion of (mis)information. The case of the Somalis moving or wishing to move to Europe is emblematic of this new scenario, where the promise of marketed commodities and fancy life styles is easily accessed with a click. Aspirations without appreciation can lead to mythologizations, and this could explain – at least in part – some of their departures. Many of them are made believe, like little Pinocchio, that in Europe they will be able to find money in the streets.[12] In a country where youth unemployment reaches quota 60–70% the remote possibility to be leading a mythical life in the West becomes very real. And this is more than enough to make up their minds. The meeting of the age of information with globalisation and consumer capitalism precipitates the young man from the local village into a global toyland. A renewed “seventh man”, or woman, in a city that is only physically distant, but virtually very real. They become “the witness of luxury” and “the sight of it… entails a promise: a promise addressed to” them.[13] While “the name of the city changes” and “continually transmits promises”.[14]

Yes, among migration determinants there is diffused violence, paralysis, ignorance, a failed state struggling to recover, and lack of opportunities. But there is also global capitalism, cunning marketing strategies, intrusive consumerism, and glossy images which continually flow from any west into the rest, periphery, or local context. If we like this market to be global, we should also expect global clients eager to ‘buy’ on Supermarket Europe. But when certain classes of migrants come close to our borders they stop being potential customers – or manufactured consumers – and they start to be problems to be solved.

These days EU Members States are struggling to find a common ground to address the migratory crisis, but they all agree in distinguishing between forced and voluntary migrants. While tentatively addressing the former, refugee quotas and sovereignty issues seem alarmingly and simultaneously the only matters at stake. Some countries are reacting vehemently, building up fences, walls, closing down borders. Others are welcoming asylum seekers, in particular from Syria. They have temporarily suspended Schengen, whilst at the same time preparing lists of safe countries to where voluntary migrants can be rejected. Yet, the expanding reality to be addressed is the one in between, that blurred zone between forced and voluntary migrations, full of concurrent national and international co-responsibilities. Titanics and* Vecchie Lire* epitomise this fundamental change in the global scenario. And Europe should be aware of this, if it does not want to miss the target.

Acknowledgements

Photo: RMS Titanic departing Southampton on April 10, 1912 – By F.G.O. Stuart (1843-1923) – Public domain.

References

“Somalia's lost generation: the battle to make migrants stay”, retrieved from YouTube on 15 September 2015, produced for Channel 4 News, UK, by Jamal Osman. ↩︎

According to an assessment made by Somaliland National Youth Organization (Sonya), in 2013 youth unemployment stands at 75% in Somaliland. ↩︎

Statistics released by Somaliland’s migration commissioner, Somalilandpress – Somaliland: “SL losing Youth to lure of Europe”, retrieved 20 July 2015. ↩︎

John Berger and Jean Mohr, A Seventh Man, Verso, 2010 edition with new preface, p. 36-37. The book was first published in 1975 by Penguin Books. Italics added, the original being in single third person. ↩︎

Interview with a refugee emergency worker in Italy, 13 September 2015. ↩︎

Clara Fringuello in Rifugiati: Vent’Anni di Storia del Diritto di Asilo in Italia, CIR, edited by Cristopher Hein, Donzelli Editore, 2010, p. 101 – 110. ↩︎

Expression in use in migration studies since the mid seventies, see Rifugiati: Vent’anni di storia del diritto di Asilo in Italia, op. cit, p. 47-48. ↩︎

For more details about forms of protection and assistance in Italy see Rapporto sulla Protezione Internazionale in Italia - 2014, as well as Progetto Melting Pot (www.meltingpot.org), Consiglio Italiano per i Rifugiati - CIR (www.cir-onlus.org), and Servizio Centrale del Sistema di protezione per Richiedenti Asilo e Rifugiati - SPRAR (www.sprar.it). ↩︎

For a first overview of actors and practices of the migration industry see Castles Stephen (Ed.) et al., The Age of Migration, fifth edition, 2014, Palgrave, p. 235. ↩︎

Op. cit., p. 221. ↩︎

For old and new theories explaining migrations see Castles et al. op. cit. Chapter 2 “Theories of Migration”, p. 25-54. ↩︎

Interviews with Vecchie Lire in Florence, July 2015. ↩︎

John Berger, op. cit., p. 136. ↩︎

Op. cit., p. 27. ↩︎