In Tbilisi, the think-tank experts, NGO directors, and other civil society actors who spend their working days debating Georgia’s foreign policy and drafting grant proposals on confidence-building or security sector reform remain donor-dependent and largely detached from wider society. Outside observers noted this around the time of the Rose Revolution, and the situation has not changed drastically. “Due to the fact that [Georgian] NGOs do not represent broader parts of society,” writes Oliver Reisner, “they often follow an agenda not directly aligned with the needs of the population. [...] The Western form of civil society therefore still remains alien to the Georgian environment as long as it is serving the ‘political’ elites.”

This dynamic has important implications, notes another commentator. Arguably, this network has narrowed the competition of political ideas in Georgia’s public sphere. Creative thinking about the Georgian government’s approach vis-à-vis its secessionist regions is rarely appreciated, critical reflections on Georgia’s dependence on the EU and the US are framed as necessarily pro-Russian or pro-government, and voices from the countryside and ethnic minorities are grossly underrepresented in policy-making.

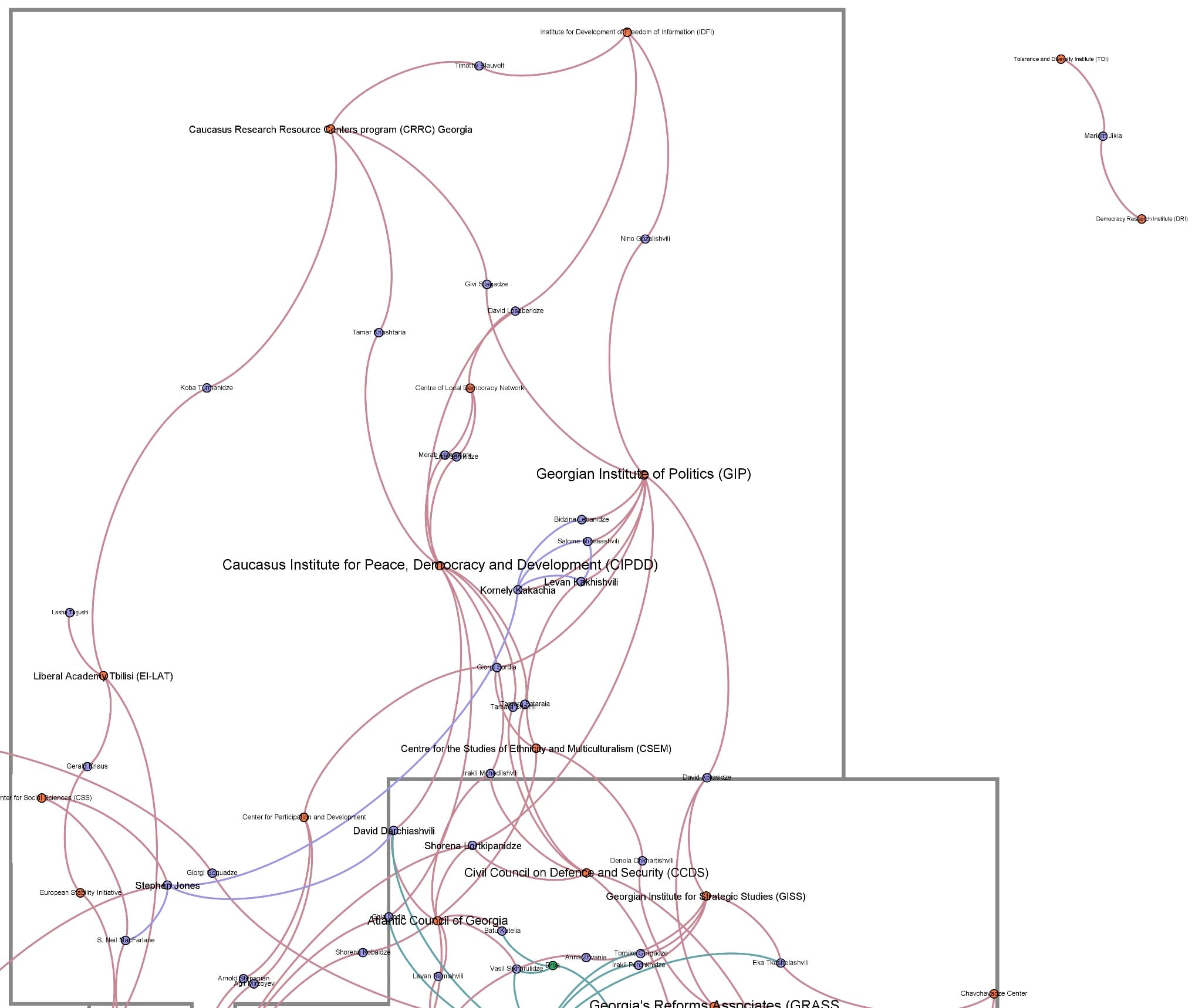

Network analysis can be a powerful tool to show how this situation is produced and reproduced. In this piece, using network analysis, l aim to show that the networked structure of ‘who gets to speak’ about security helps us better understand how other voices are excluded from (geo-)political debates.

Sociologists have long studied networks of policy-makers, think-tankers, elites, and professionals. A number of – mostly Dutch – academics has researched corporate power elites by mapping C. Wright Mills’ concept of ‘interlocking directorates’ – instances where members of one corporation or institution sit on the advisory board of another. Leonard Seabrooke and his colleagues have drawn on Andrew Abbott to show how networks of transnational experts emerge and claim ‘jurisdictional control’ over governance issues. Bourdieusian social scientists have examined how influential actors in knowledge production are positioned at the interstices of policy, academia and media.

But this kind of cutting-edge critical work is rarely applied to the formation of expert knowledge and public policy in small semi-peripheral countries in Eastern Europe and Eurasia, such as Georgia.

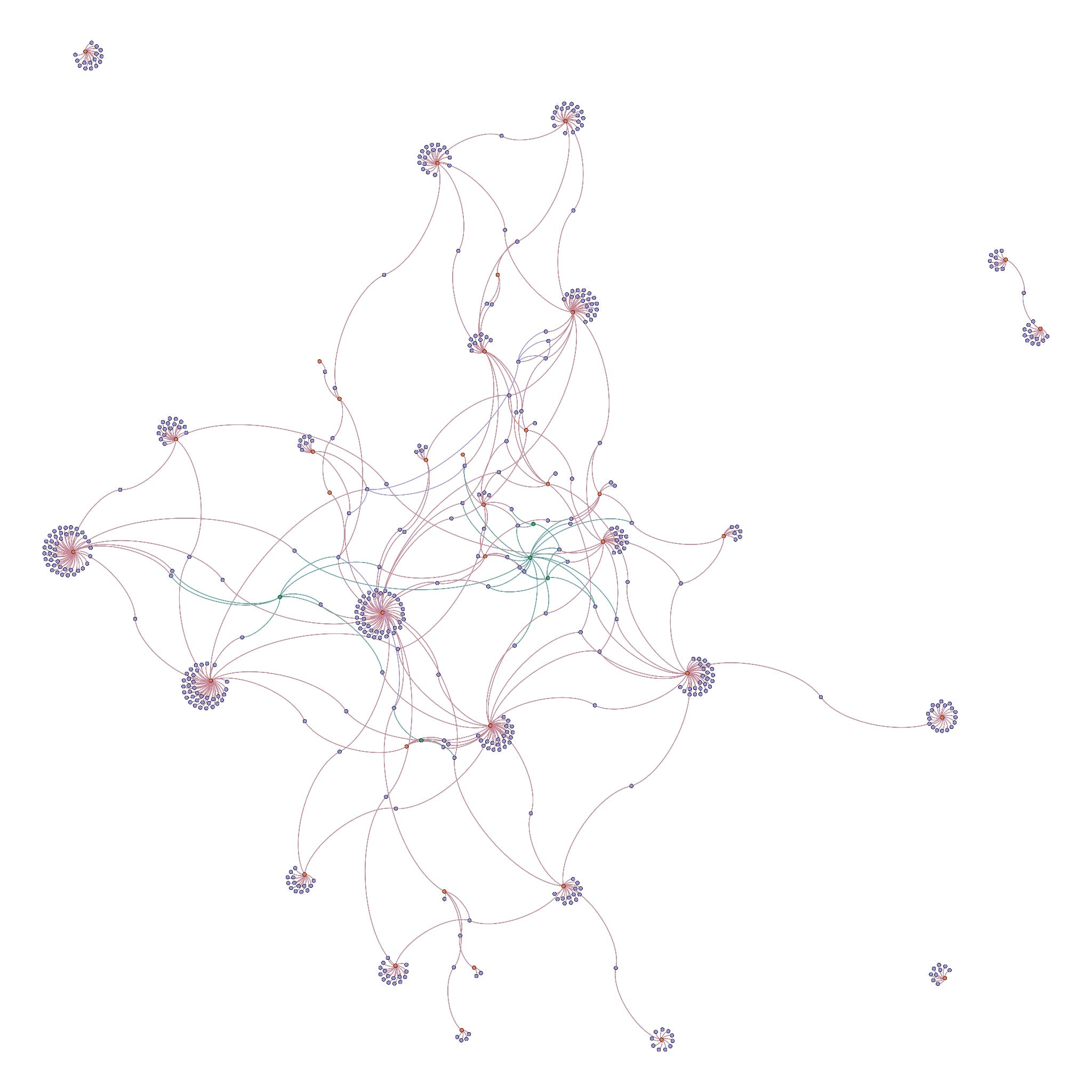

The network graph below (Figure 1) shows the connections between 37 Georgian organisations, ranging from think tanks to NGOs to consultancy corporations (red); 489 employees, fellows, board members, affiliated researchers, and so on (violet); and 5 political parties (green). This visualisation is based on my own data collection work, using publicly available data on the organisations’ websites (sometimes using the Internet Archive).

There are also certain limitations to it. For example, I do not differentiate between different types of professional relations (e.g. between senior and junior researchers; or mentor/advisor relationships) or more intimate relations (family or friendship). Connections in the past are also not always well-documented, and defunct organisations are not included. A more substantive limitation is the focus on formal (non-governmental) organisations as such. Furthermore, a more comprehensive, Bourdieu-inspired analysis would chart the entire field of security expertise, which includes among others actors in (semi-)governmental agencies, universities, media corporations.

These limits notwithstanding, much can be observed just by glancing at this network structure. A typical organisation in this network employs a large number of analysts, project managers and fellows, but only one, two or three key figures that are tied to a number of other organisations – through former positions, joint appointments or board membership. Almost all the organisations are somehow interlinked via these key figures, and there are just a few peripheral unconnected or poorly connected organisations. There is clearly a more well-connected inner network and an outer ring of actors. Three political (opposition) parties are part of the core.

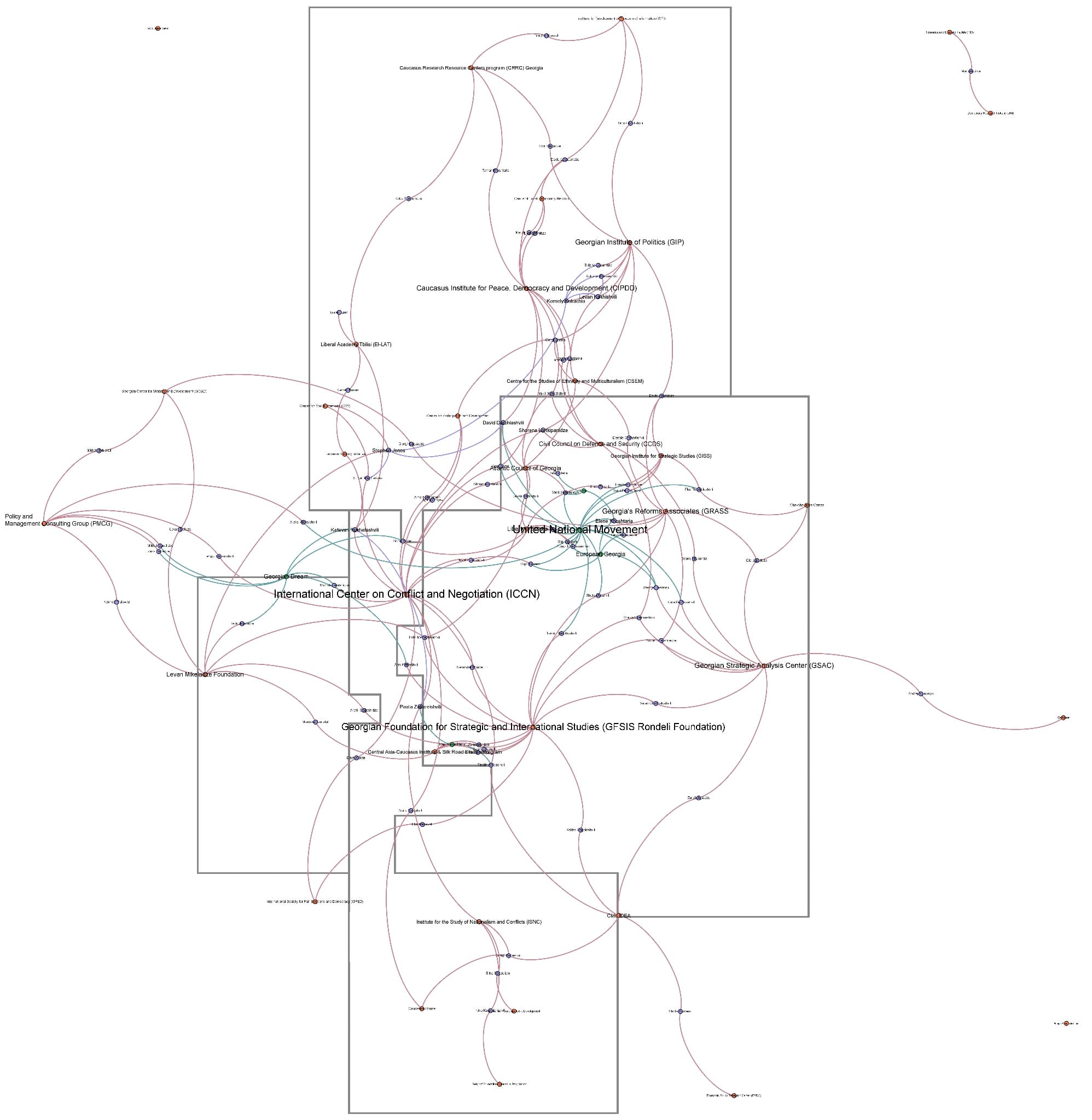

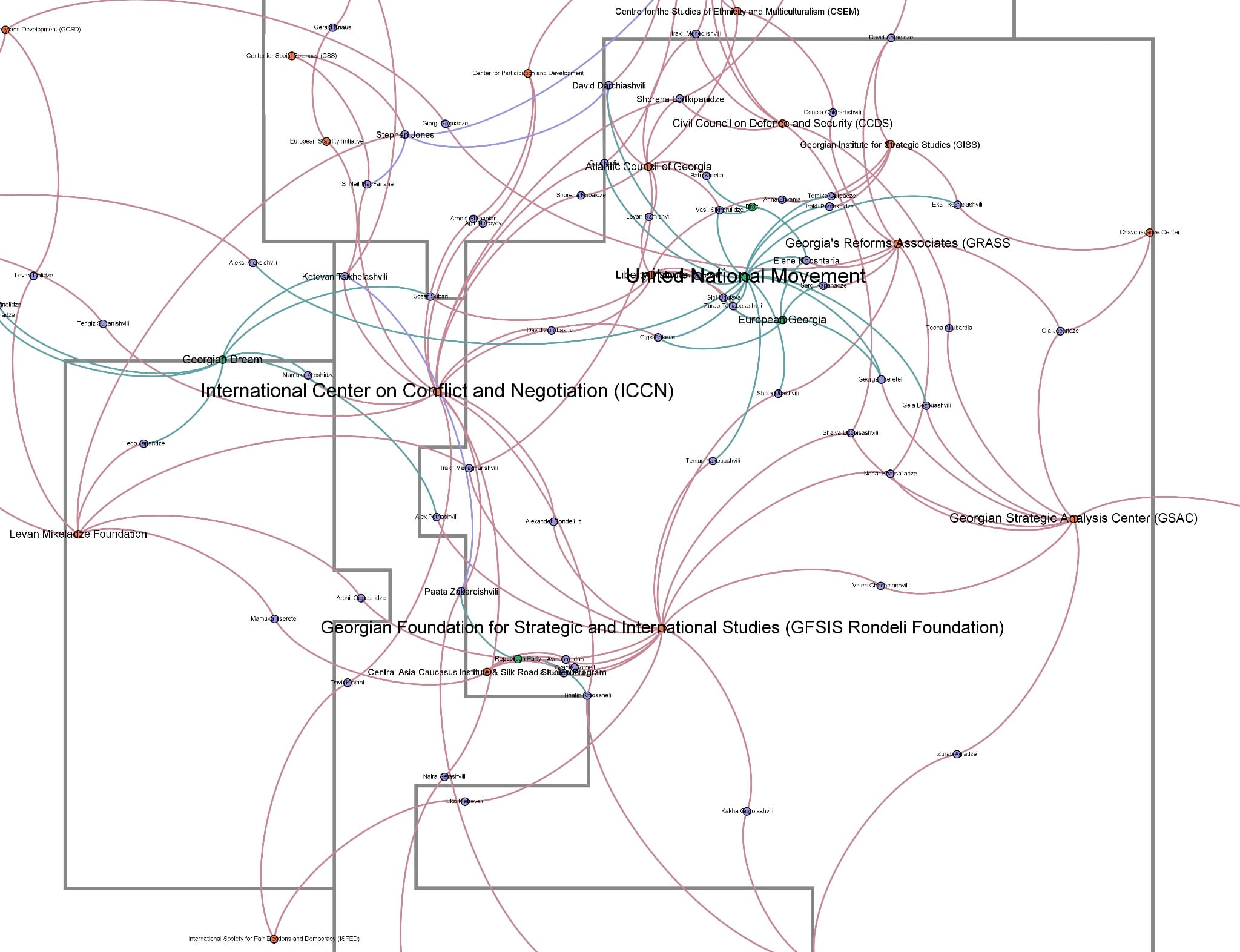

By adding labels and by only including those actors that are linked to more than one other actor, the network graph becomes more legible (Figure 2). In the centre of the security policy-making network we find the famous Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies (GFSIS), co-founded in 1998 by the late Alexander Rondeli, and the now less-active International Center on Conflict and Negotiation (ICCN), founded in 1994 by the late George Khutsishvili. Despite being interconnected, the invisible dividing line between these two organisations is significant in terms of the ‘division of expert labour’. GFSIS was the first true security think tank, whereas ICCN initiated the carving out of civil society niches for those more interested in research and mediation than in geopolitics.

In the central rectangle around GFSIS, we find primarily organisations interested in ‘hard’ security, geopolitics, and governmental reform, such as the Georgian Strategic Analysis Center (GSAC) and Georgia’s Reform Associates (GRASS). The latter is tightly linked to European Georgia (EG), a political party founded by members who broke away from Saakashvili’s United National Movement (UNM). The projects implemented by these organisations bear names such as ‘Russian military analysis’, ‘NATO media training’, or ‘program for civil service leaders’.

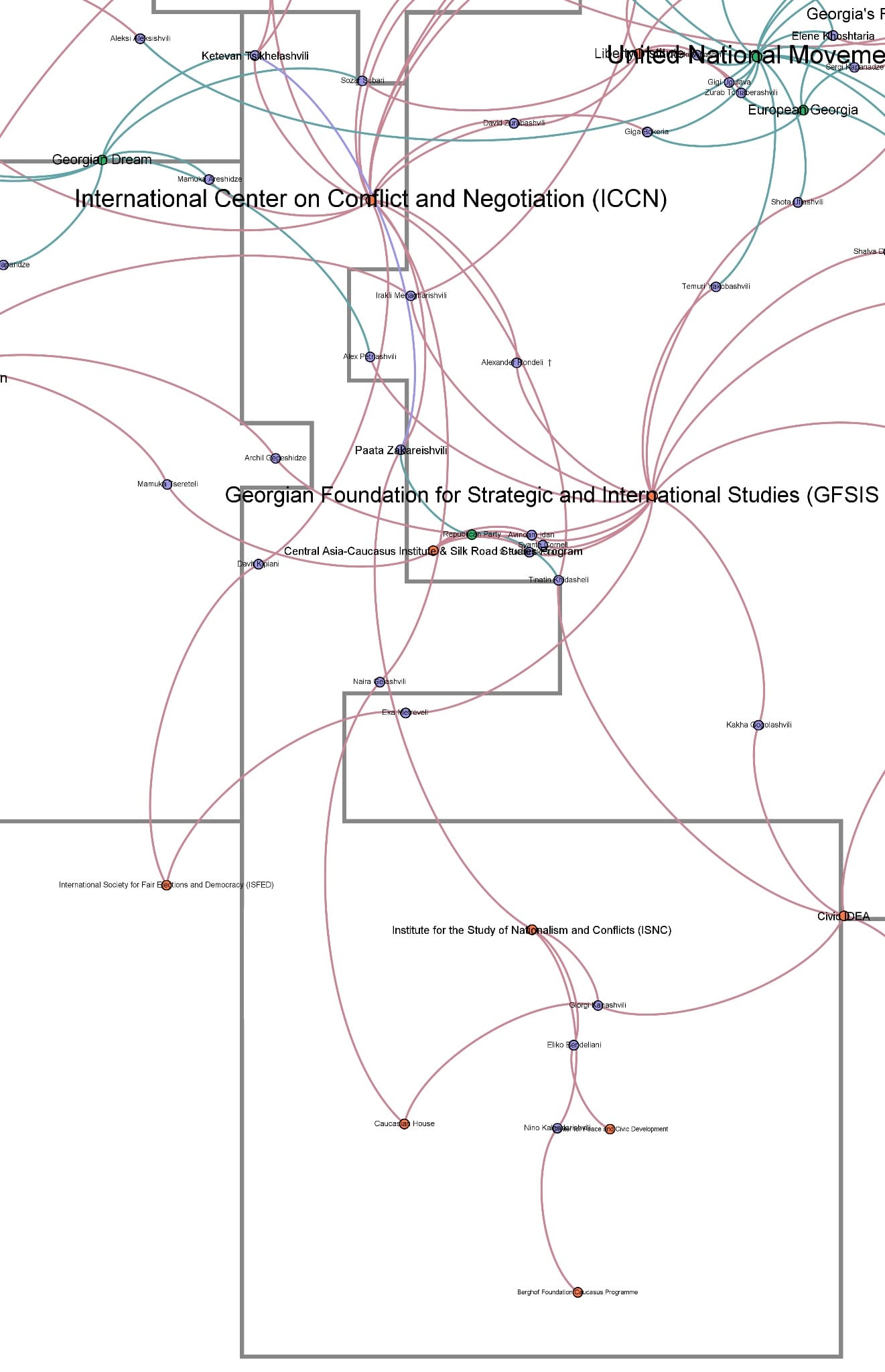

In the L-shape that cuts through the central rectangle (from ICCN down to ISNC), by contrast, we find organisations involved in conflict resolution, peacebuilding and civil society ‘capacity-building’. Here one is less likely to find projects on national security and more likely to encounter online dialogue projects bringing together Georgian, Armenian and Abkhazian youth. This side of the network includes important former officials who held posts in post-Saakashvili governments, such as Tinatin Khidasheli, Paata Zakareishvili and Ketevan Tsikhelashvili.

Finally, in the rectangle on the top, we find organisations that are primarily concerned with political science research and democratic development. This includes the Caucasus Institute for Peace, Democracy and Development (CIPDD) and the Georgian Institute for Politics (GIP). They organise democracy schools for youth and public discussions on the regional impact of the Russian war in Ukraine, and write reports on religious pluralism, political crises, and the far-right. An interesting side-note is that while GIP is gaining in prominence and reputation (also abroad), it is not so centrally located in the network. Instead of truly competing with the organisations in the central rectangle, it has carved out a niche for itself, preferring specialised academic research on the Europeanisation–foreign policy nexus over Tbilisi’s heated partisan security politics.

In terms of partisan connections, it is clear that the former ruling and now opposition parties (UNM, EG, and the newest split-off Droa) are much more entangled with the security governance think-tank/NGO network, than the currently ruling Georgian Dream party. Overall, the network is dominated by a centre-right ideological orientation. Organisations with left-leaning members are found on the periphery of the network (e.g. Social Justice Center and Caucasian House), and such organisations have more to say about cultural and human rights issues and are hardly influential on foreign and security policy.

What can be said on the ethno-national identities and linkages illustrated in the database? Of the 489 people that I have included, 97 have non-Georgian surnames. The vast majority of these people are Americans and Europeans who serve on international advisory boards or work as academics in Tbilisi. Only 15 individuals (3 per cent of the sample) are Georgian citizens with an ethnic minority background, such as Azerbaijani-Georgian, Ossetian-Georgian, Yezidi-Georgian or Armenian-Georgian. Almost none of these people are in leadership positions. Overall, it is clear that ethno-national minorities are underrepresented in this policy network (ethno-national minorities constitute 13.2 per cent of Georgia’s total population according to the 2014 census).

Of the ‘foreigners’ in the network, the most prominent nationality is, by far, American (38.8 per cent in my sample). Americans are followed by Brits (13.8 per cent) and Germanophone Europeans (German, Austrian, Swiss) (also 13.8 per cent). The number of connections to Central-Eastern Europe (Ukraine, Poland, Czechia, Romania, Baltics) is also not insignificant (10.0 per cent). Interestingly, some institutes (e.g. GIP) are more Europe-linked, whereas others are closely tied to the US (e.g. GFSIS), which is also reflected in more policy outputs related to the EU/Eastern Partnership vs. NATO/US strategic cooperation.

Via advisory or affiliate positions, Georgia’s security policy actors are associated both to very well-regarded academics such as Thomas Risse and Stephen F. Jones, as well as to rather controversial organisations like the European Values Center for Security Policy in Prague (whose members hold fairly problematic positions on Islamism, and are involved in a hysterical search for a ‘fifth column’ supporting ‘Russian hybrid warfare’ in Czechia and the rest of Europe) and the Institute for Security & Development Policy (ISDP)/Central Asia-Caucasus Institute in Stockholm/Washington D.C. The ISDP has links to the Aliyev regime in Azerbaijan, and is funded by not only the Swedish MFA but also a dubious Azerbaijani construction company.

What can we learn from this rudimentary analysis? On the one hand, the network is highly concentrated, centred around a small number of key organisations. Ethnic minorities are heavily underrepresented. Very few organisations manage to be both influential and remain unconnected to one or more of the ‘big players’, which is potentially problematic. It reinforces a circulation of the same kind of ideas and people. On the other hand, the network is not homogenous: different organisations cluster around different niches, which provides the policy sphere with some more diversity. There are also a number of newer and more heterodox organisations on the fringe of the network – left-leaning NGOs, economics-oriented consultancy firms, and others. It remains to be seen whether these will drift to the centre and become entangled with the established actors, or whether their fresh blood will carve out separate yet influential niches for new kinds of public policy expertise. All of this should be relevant to donor actors who keep wondering why civil society in Georgia remains somewhat detached from the wider population. Even in times of war and crisis, creative policy thinking should be encouraged.

Cover photo © Office of the State Minister of Georgia for Reconciliation and Civic Equality, 2019