Researcher safety in peace, conflict and security studies in Central Asia and beyond: Making sense and finding new ways forward.

The safety of researchers is a pressing issue, with ever new incidents of scholars and journalists being detained, interrogated or otherwise scrutinised by security forces both in Central Asia and the world over. We present here an overview of a recent roundtable held during the Joint CESS-ESCAS Conference in Bishkek in June 2017. Panellists and audience provided critical reflection on present contradictions and new ways forward for scholars interested in social and political dynamics in Central Asia. Participants discussed the different actors involved in the global political economy of knowledge production in, and on the region. Besides, they attended to the practical and ethical dilemmas of whether and how to adjust to the increased publicity, exposure and danger faced by researchers.

Part I — Presentations

The first speaker, John Heathershaw (University of Exeter), reminded attendees of the detention of Alexander Sodiqov in 2014, his research partner at the time, by the Tajik GKNB (State Committee for National Security) on charges of espionage. Without going into the detail provided in other discussions, Heathershaw demonstrated how this case exemplified the dilemmas and trade-offs of critical research on politically salient topics in Central Asia. Given the widely-perceived necessity to produce research that influences practices and policies of governments and other actors, academics find themselves compelled to generate publicity and open debate, e.g. by writing blog-posts and other online formats that present investigative findings. On the other hand, as government actors are increasingly keen to control narratives (see The closure of academic space in Tajikistan: How should foreign scholars and institutions respond by John Heathershaw and Edward Schatz, to be published soon) about their actions or events in their country, protecting one’s identity by e.g. publishing under a pseudonym becomes increasingly important. Research done in cooperation with authorities would not be less risky, at least for research participants, argued Heathershaw, as the latter’s anonymity and safety in the aftermath of such projects is hard to guarantee. Overall, currently prevalent ways of dealing with issues pertaining to peace, conflict and security research appear to be insufficient, as Ethical or Institutional Review Boards maintain their formalistic approaches, which make students adapt their research frameworks but are ultimately unable to prevent risks, insecurities and actual incidents in field sites. In this light, Heathershaw emphasised the need to further explore possibilities of activism and solidarity among academics and of gathering and sharing researcher’s experiences and knowledge about dangers faced in different field sites.

This view was corroborated by Karolina Kluczewska (University of St Andrews), who told about her six-months-long ethical review procedure in her institution, during which she was repeatedly instructed to provide detailed questionnaires and lists of interviewees, as well as consent forms signed by interviewees. Such measures and the overall process appeared to be of little use given the evolving dynamics of fieldwork, especially in Kluczewska’s case, as her fieldwork is based on long-term residence in Tajikistan and cooperation with local NGOs. She presented this approach, including affiliation with a local institution/university and engagement with the domestic academic community, as the most reasonable for gathering genuinely new insights about international development programming in Tajikistan. Issues of danger and legal action against researchers were not always due to authorities’ overzealousness, she argued, as many researchers undertake research without any deeper knowledge about the country’s customs and local languages, and conduct research after simply obtaining tourist visas instead of a research permission. This approach is particularly dangerous for researchers and research participants, as it circumvents legal restrictions and thus puts everyone involved into a vulnerable and potentially dangerous situation. Kluczewska also highlighted the fact that international NGOs and international organisations in Tajikistan rarely provide substantial information on their activities and, in her experience, their staff are the ‘people most difficult to reach’; a fact which makes surreptitious research and publication practices of researchers more understandable.

A further example of research with profound safety implications was provided by Sam Fife from Search for Common Ground Kyrgyzstan. He explained how the organisation took a careful approach towards its research on radicalism among Kyrgyz, Uzbek and Tajik labour migrants in Russia by allowing enough time to lay the groundwork and developing a credible methodological approach together with its partners in Russia and the UK. Partnering with an in-country research institution, which received assurances from state security that they would not object to the research project during the inception phase, was indispensable for preventing irritation during the research. Local researchers accompanied Central Asian research teams to assist with logistics and ensure that local law enforcement would allow the fieldwork to move forward unhindered. But such cooperation also required careful consideration of the confidentiality and possible safety issues arising for participants in the study. This was partly achieved by providing outputs with different levels of detail to the respective government or local governments and the public, and by conducting interviews in Central Asian languages. Agreeing on research framings and questions that did not seem threatening or dangerous for local authorities in this case proved productive to avoid issues of safety and irritation.

Zhyldyz Tegizbekova, Associate Professor in International Law and Human Rights at the International Alatoo University in Bishkek presented her perspective on the legal framework for academics doing research in Kyrgyzstan. She affirmed that researchers were generally free to do any kind of research they wanted. However, she added that the law on national security agencies describes the latter’s task to protect individuals, society and the state from unlawful acts which negatively affect or damage social order and national security. This meant, according to her, that agencies deemed it necessary to control research on certain topics by way of ‘cooperating’ with researchers so as to ensure that they do not breach laws pertaining to public order. Besides the increased importance of aspects of national security since 2010, the incitement of ‘interethnic enmity’ — after article 299 of Kyrgyz Republic’s Criminal Code — was increasingly seen as an issue in academic research. While lists of indexed research topics are kept secret, and no one can know which kind of research will come under scrutiny, Tegizbekova posited that ignorance of the country’s laws (including the above) would not exempt any researchers from being queried by security or law enforcement organs. She further argued that researchers should keep in mind that when doing interviews in the country’s communities, there is a realistic possibility that people complain to the police and investigations are opened.

The final panel speaker, Alisher Khamidov, shared his experience from doing research on Islamic identities in Northeast England. A key encounter for him was a conversation with two imams in a Newcastle mosque, which turned into an interview during which the imams queried him as to the reasons and intentions of his research, given that it was funded by the British government. He soon ended the interaction and himself, as he had not expected such an experience in a country and Muslim community he thought would be more open for conversation. This bears resemblance to the situation in Kyrgyzstan, where building trust with interlocutors takes a long time and requires some kind of peer pressure, e.g. befriending the wider social circles of research subjects. Khamidov further pointed out how doing research supported by governments – or other major actors – is not always a liability but can also prove an asset when interlocutors see interviews as a chance to voice their grievances and make use of the researcher as a mouthpiece, if not a counsellor. Another contradictory aspect of field research, as Khamidov pointed out, are the widely perceived dangers associated with going to certain ‘criminal’ areas or places/events known for hostilities or attacks by nationalists, e.g. football games, all of which turned out to be harmless in his case. This once again underlined the issue that, until they materialise, dangers and risks of fieldwork rarely appear significant and might seem non-existent all along.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to all participants for their involvement in the discussion and for being ready to have their contributions included in this summary. Special thanks to Nurbek Bekmurzaev for co-convening the roundtable and providing valuable input on the text.

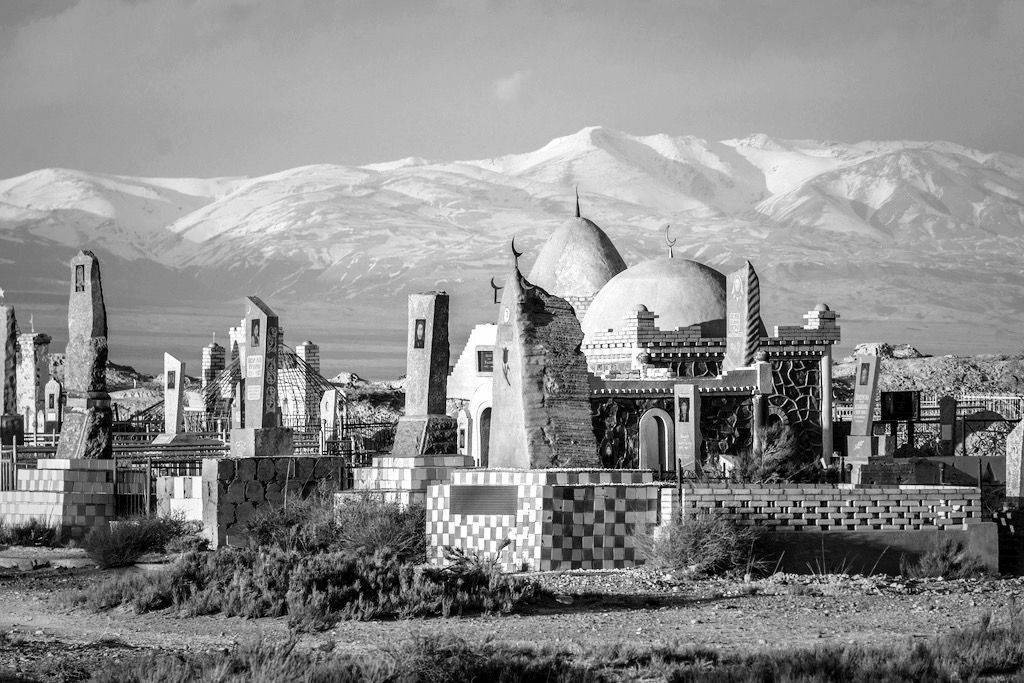

Cover photo: Ronan Shenhav, Kyrgyz Muslim Cemetery, (CC) 2017.

Inline photo: Lucas Verheij, Yurt near Issyk Kul, (CC) 2017.