In July 2019, the Nigerian army announced a new strategy in its war against the Boko Haram insurgency sweeping the North-East of the country. In spite of a resolute approach to solving the crisis and some initial successes, President Buhari’s anti-terror campaign had proven unable to reform the Nigerian military to an extent that its lack of equipment, low numbers and payrolls, and soldier’s motivation could stand up to the insurgents. Boko Haram’s attacks became more and more frequent in mid-2018. Insurgents, mainly from the Dawla faction, focused their strikes on military ‘forward operating bases’ (FOBs) along the fringes of Lake Chad and northern Borno and on mobile units. However, as the strategy has been seen more as an improvised plan rather than a well-structured and forward-looking one, many have questioned if Buhari has not made a virtue out of necessity.

In this context, the new ‘Super Camp’ strategy (SCS) came as the result of multiple factors, mainly of military nature: first of all, the continuous attacks which almost doubled the number of casualties among the Nigerian army; secondly, the FOB’s intrinsic vulnerability due to inadequate manpower and equipment, which made them subject to frequent raids and arms theft; finally, inadequate management of soldiers’ rotations, some of which would be deployed in the same area for over four years with massive impacts on the troop’s morale and their fighting willingness and capability.

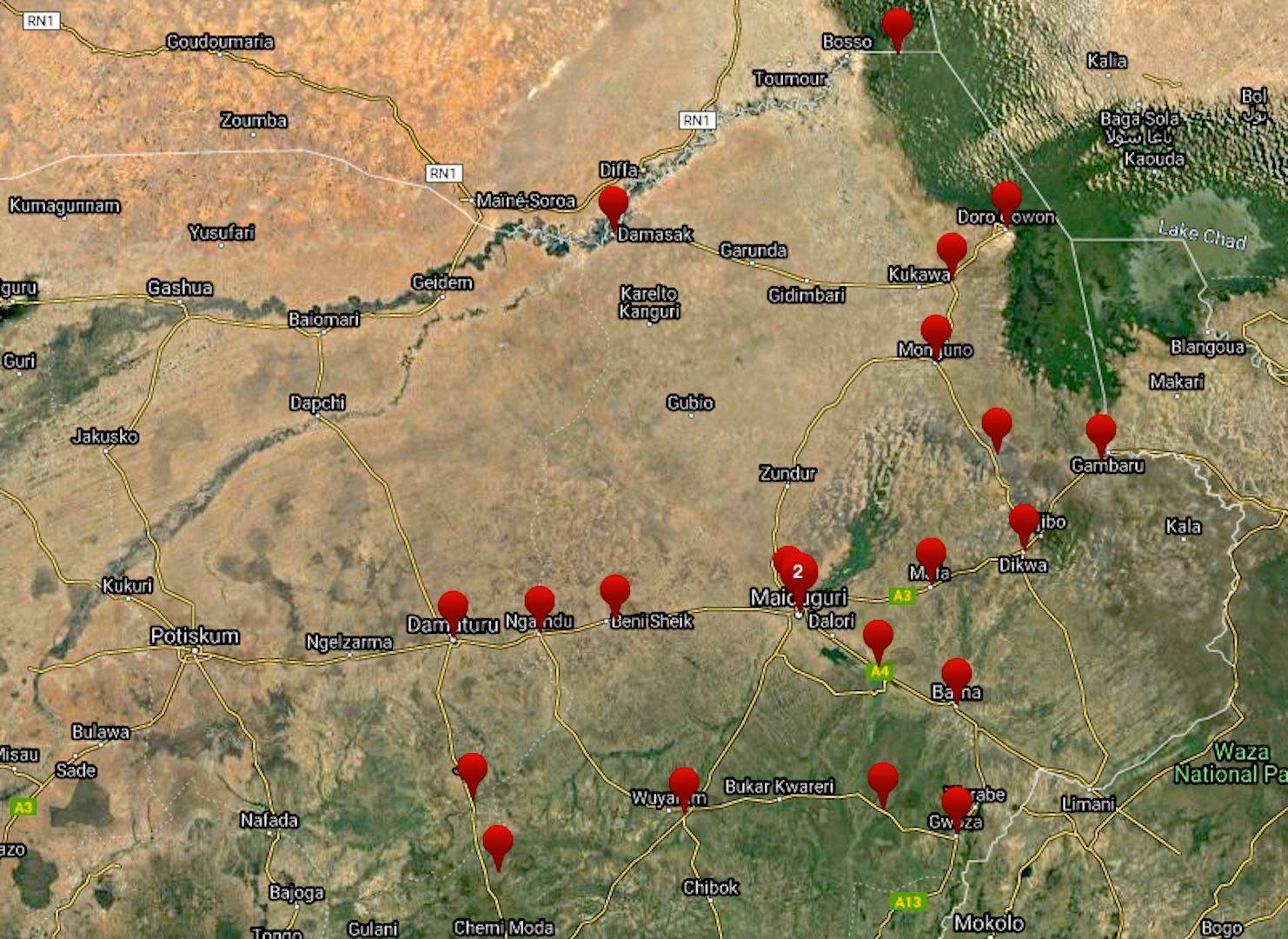

In a nutshell, the new strategy consists in concentrating soldiers in so-called “super camps”, few well-constructed military strongholds where civilians and the rural population either live or are compelled to move, and which are consequently guarded against being overrun. At the same time, smaller military outposts with a higher probability of being stormed are dismantled: they have become the target of insurgents as a means to increase their power and strengthen their capacity. From the super camps, the army should be able to quickly respond to threats in the region and raid militant outposts, reducing both military casualties and theft of equipment, as well as enhancing the protection of vulnerable communities. While announcing the building of 20 super camps (September 2019), Army chief General Buratai described them as “the concentration of formidable fighting forces in strongholds that have the capacity for swift mobility”. The claim is to replace the missing static presence on the territory through dynamic patrols, following the motto “No occupation, but domination of the territory” [1].

However, it is important to highlight the deep gap between official statements and reality, which, given the extreme humanitarian situation at hand, is crucial to consider.

First of all, super-camps aren’t exactly a new concept, but are a development of the already existing garrison towns. The original idea of 2015 was to bring people from rural areas, also forcefully, to few fortified towns or enclaves; erect IDP camps for the newly displaced people, which often ignored most basic needs; and build trenches around the perimeter to consolidate the military presence [2]. The super-camps are therefore the fortified exacerbation of an already existing structure, notwithstanding that the same concept of “fortification” is rather ambiguous, as increasing the number of observation posts and of soldiers does not necessarily correspond to an increase in efficiency of protective measures.

Secondly, although the strategy was firstly announced in July 2019, its implementation was done in three consecutive waves: until 2018 the number of military outposts increased across the whole northeastern territory; from 2018 until July 2019, any FOB too small in size was systematically overrun by insurgents, which led to a process of concentrating resources in a smaller number of bases; by July 2019, the official declaration of the SCS was made, but the reality shows that this was just the formalisation of an already existing endeavour [3]. Albeit the claim towards international donors and partners was to better protect civilian areas, the underlying reasons root in the limited operational capacity and the growing level of military casualties, a political price the Government was determined to avoid [4]. As so often already, the highest toll was paid by the population and humanitarian organisations: civilians especially in unguarded areas were left at the mercy of the violent insurgent groups, whereas humanitarian organisations were forced to reduce their activities or face mounting security risks [5].

Thirdly, what has apparently been a tactical withdrawal of the Nigerian troops from smaller outposts, has really been the gradual replacement of the latter with Chadian troops, which had already been in the country since 2015, brought-in in the frame of the Multinational Joint Task Force to fill the voids [6]. This replacement was done only a few weeks after the official declaration of the SCS in response to the vacuum that allowed NSAGs to roam freely and take possession of those parts of territory left voluntarily unprotected.

The narrative surrounding Chadian soldiers sees them as being proud, highly motivated and “willing to take the fire” [7]. Nonetheless, despite this comparative advantage, President Deby ordered their withdrawal in December 2019, considering its mission, and motivation, in North-East Nigeria concluded. It was only thanks to the request of Borno State’s Governor Zulum, at the expense of Nigeria’s military pride, that the troops were reportedly re-deployed at the end of January. Although in such a fluid environment the SCS was never meant to be a long-term goal, and rumours say that it is inscribed within a bigger picture of new aerial warfare, this replacement still affected the strategy’s architecture and the plummeting morale of the Nigerian soldiers, adding up to the widespread feeling of surrendering territory to the insurgents.

Finally, as paradoxical as it may seem, the troops’ consolidation into super-camps corresponded to an intensification of attacks in particularly in Borno [8]. NSAGs were left free to reorganise themselves and set up illegal checkpoints on the crucial roads, resulting in killings and abductions. ISWAP’s territorial range increased, and its calls on the population through preaching spiked, with the usual nocturnal raids giving way to daytime incursions, destruction and a generalised sense of vulnerability. Fuelled by feelings of abandonment and disappointment among civilians, the forced displacement and vulnerability caused by the SCS further increased the chasm between the population and the army, and many considered living under ISWAP as the lesser evil [9]. Humanitarian organisations saw the constriction of an already little humanitarian space, dangerous access constraints, stark deterioration of relations with the military, and an overall reduction of their humanitarian response [10].

The strategy has indeed “stopped the bleeding” in terms of exposure and military casualties but it has possibly opened a far deeper wound, demonstrating the inherent weakness of the Nigerian army, its unstructured territorial view and humanitarian neglect [11]. By leaving the weakest FOBs behind, the Nigerian government has not only abandoned civilians and momentarily declared forfeit of its will of resolving the security crisis in the North-East, but also damaged its reputation among its regional partners, especially Chad, as the leader in the war against one of the most aggressive threats to the region’s peace and stability of our present times.

In its purest version, the 'super camp' strategy was a tragic blunder for which the Nigerian government quickly sought alternatives. Clearly lacking a structured underlying vision, building super camps can hardly be called a strategy, and their failure fuels uncertainty in the future of North-East Nigeria.

Footnotes

- Wolf, S., (2020, 19 May). Personal interview. Security expert source that has requested to stay anonymous.

- Ibidem

- Ibidem

- Wolf, S., (2020, 07 May). Personal interview. Expert source that requested to stay anonymous.

- Wolf, S., (2020, 06 May). Personal interview. Humanitarian expert source that requested to stay anonymous.

- Wolf, S., (2020, 07 May). Personal interview. Humanitarian expert source that requested to stay anonymous.

- Wolf, S., (2020, 19 May). Personal interview. Security expert source that requested to stay anonymous.

- Ibidem

- Ibidem

- Ibidem

- Wolf, S., (2020, 07 May). Personal interview. Expert source that requested to stay anonymous.

References

David, T., Nigeria: Army’s Super camp Concept and Quest to Uproot Insurgency, Leadership, 12 September 2019, retrieved from https://allafrica.com/stories/201909140059.html.

Foucher, V., 23 January 2020, available at https://twitter.com/VincentFoucher/status/1220269389783740416 (Accessed: 12 June 2020).

Nguedmbaye, M., Tchad: les soldats en intervention au Nigeia sont rentrés définitivement, Tchad Infos, 3 January 2020 retrieved from https://tchadinfos.com/politique/tchad-les-soldats-en-intervention-au-nigeria-sont-rentres-definitivement/.

Omilana, T., Super camps make Nigerian Army “less nimble” against terrorists, TheGuardian, 7 October 2019, retrieved from https://guardian.ng/news/super-camps-make-nigerian-army-less-nimble-against-terrorists-report/.

SB Morgen, Stalemate: Boko Haram’s New Strategy Requires It to Commit Fewer Attacks, September 2019.

Stoddard, E., Are Some Sahelian Jihadists Groups “Antifragile”?, Security Praxis, 10 February 2020, retrieved fromhttps://securitypraxis.eu/sahelian-jihadists-antifragile/.

Expert sources working in the territory were consulted.

Acknowledgements

Cover photo source https://twitter.com/defensenigeria/status/1272980381625733122