Myanmar arguably hosts one of the largest concentrations of state-repelling ethnic minorities. Nevertheless, with the gradual occupation, co-optation and articulation of physical and social spaces and structures by central authorities, the only environment that seems left to them is that of illegality, often once again defined by and in mutual relation with the state.

The beginning of 2018 in Myanmar was characterized by repeated clashes between the Tatmadaw (Myanmar Army) and several so-called Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs). In Shan State, the Tatmadaw clashed repeatedly with the Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army-South (RCSS/SSA-S) in the areas of Loilen, Mong Ping and Kyethi Townships. In the south-east of the country instead, the Border Guard Forces (BGF) launched attacks against the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (DKBA-5/Klo Htoo baw Karen Organization, KKO) in Mae Tha Waw area, Hlaingbwe Township.[1] Active conflicts in the north of the country against Kachin and Ta’ang groups, as well as between the latter and the RCSS/SSA-S, also escalated.

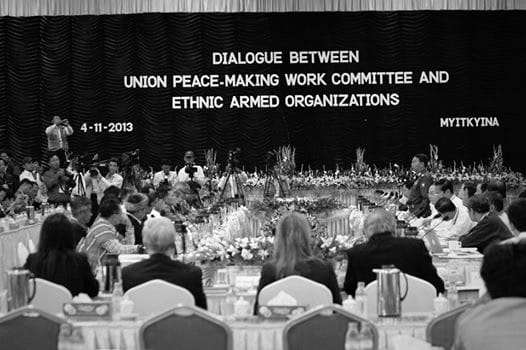

At the same time, the Tatmadaw obstructed national-level political dialogues and public consultations held by the RCSS/SSA-S, the Arakan Liberation Party (ALP) and the All Burma Students’ Democratic Front (ABSDF). As a consequence, the leaders of the eight EAOs signatories of the 2015 Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) decided that the third session of the 21st Century Panglong Union Peace Conference (UPC) scheduled for the end of January should be held only after the dialogues and consultations mandated under the terms of the NCA have taken place.[2]

Amidst heightened tensions, these events and the third session of the UPC eventually postponed to February offer an opportunity for reflecting upon the strained relations between the Tatmadaw, the government and ethnic organizations in Myanmar. One underlying trait of the relationship between these entities is the unfolding of mutually constitutive state-building processes of various nature, in which the State retains a privileged position vis à vis its opponents.

Within the landscape of Myanmar’s decades-long civil war, one can observe the persistency of a panoply of practices and narratives through which the government and the Tatmadaw have shaped insurgencies into organizations of different nature and form, to the detriment of bottom-up spontaneous pushes for autonomy.

On the other side, state-resistant groups have often undertaken trajectories of government that draw around them the effigies of state builders. Similarly to other techniques of social identity, the organization of insurgency structures “offers a powerful way of creating a place for new elites and an institutional grid for social mobilization.”[3] Ironically, those structures move somehow closer to what they sought to take distance from. The state, directly or indirectly, plays a role in the formation, institutionalization and transformation of insurgencies.

During the last 70 years in Myanmar, the military governments of the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) and Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), together with the Tatmadaw, have adopted a whole range of tactics that practically and physically constructed the borderlands of the country. Not only physical space was targeted, but also the configuration of what James Scott termed “state-repelling” societies and the EAOs representing them in the armed struggle [4].

In the years, the military and the government have managed to organize spaces and people outside their direct control. Tactics adopted to this end have been particularly varied.

The co-optation of local business or political figures together with the creation of patronage networks, the constitution of paramilitary groups out of disbanded EAOs units or the concession of construction contracts for infrastructures to local, national or regional actors represent some examples.

The transformation of EAOs into paramilitary entities somehow connected to the Army has represented a major tenet of the Tatmadaw’s counterinsurgency strategy since the 1960s. [5] This modus operandi has assumed different incarnations, from Ne Win’s program aimed at molding Shan State armed actors into state-backed KaKweYe (KKY) paramilitary units to the prominent role of people’s militias in the Maoist-inspired concept of people’s war widely embraced by the Tatmadaw or the more recent 2009 Border Guard Forces (BGF) reintegration program.

For instance, the 23 BGFs and 15 People’s Militia Forces (PMFs) emerged in 2009 and 2010 from former ceasefire EAOs, EAOs’ defecting factions or other militias and today form an effective branch of the Tatmadaw. The latter controls them directly or through patronage relations with prominent local figures. In turn, rural areas, particularly in the north and east of the country, are characterized by a complex and discontinuous political and security landscape presenting multiple centers of power. [6]

Another such means is the allocation of large-scale portions of land that allows the military and the government to pose as security providers, extract resources of different kind from the surrounding areas, establish partnerships with the new owner(s) and intervene on the social configuration of the territory through relocations and administrative settlements. [7]

The so-called “4-cuts” strategy, featured prominently in counter-insurgency manuals of the Tatmadaw, is equally illustrative in this sense. Overall, the strategy’s rationale resides in the disconnection of communities from insurgent armed groups and vice versa, in order to shape local armed actors as completely separate entities from the underlying population. In fact, the strategy consists in cutting off intelligence, food, funds and popular support for insurgents in order to destroy or force them into co-optation processes. The tenacious refusal of EAOs to disarm after having signed ceasefire agreements with the government might in part be interpreted as an indication of the reluctance to undertake the very last step in that direction and the willingness to continue moving along centrifugal trajectories of government.

Through these techniques the central government structures its borderlands. It squeezes out the fluidity of those rejecting the central state by molding their organization.

Quite tellingly, the Security Sector Reform (SSR) and Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) processes represent one of the most essential, delicate and controversial components of the peace process codified in the NCA.

In the 2015 Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement the two are defined with one single term, “security re-integration”. The synthesis of SSR and DDR into this formula has engendered ambiguities in the peace process. Depending on interpretation, such an equation might entail the dismantling of EAOs and their incorporation into the current state security apparatus without any concrete reassurance concerning the modification of the latter into a more federal security system or any actual reform in that direction prior to the disarmament of EAOs. Not surprisingly, these issues generate frictions between ethnic organizations, the government and Tatmadaw. In January, the Karen National Union/Karen National Liberation Army (KNU/KNLA) officially declared the necessity to postpone the upcoming Panglong UPC adducing exactly the persistence of this controversial matter. Divergences on SSR and DDR shed a light on mutually constitutive processes of state building as they lie at the core of structural and organizational aspects of both sides, bringing to the fore fundamental questions such as the monopoly over the use of force.

As the relevance of wordings in relation to SSR and DDR arrangements suggests, the forms assumed by these processes have by no means been limited to practices. Narratives and discourses also bear a role. Although in a subtle and marginal way, a recent event provides a hint of how mutually constitutive processes translate into words.

During his relatively recent apostolic journey to Myanmar at the end of November 2017, Pope Francis’ avoidance of naming the Rohingya sparked debate. The Rohingya people is one of the ethnic minorities of Myanmar – although not considered as such by the government and kept outside the count of the 135 officially recognized ‘national races’. The international public opinion had recently awakened to their struggle due to the Tatmadaw’s last wave of repression burst out in August last year and still ongoing during the Pope’s visit.

Besides the indignation aroused, the absence of the name ‘Rohingya’ in the Pope’s speech might be understood as a narrative fragment of the relationship between sovereign powers and “state-repelling” people. Against the backdrop described above, the term Rohingya becomes conspicuous by its absence in Pope’s speech. On the one hand, naming all the minorities in conflict with the state would have been perhaps impractical (in fact, the Pope did meet with a delegation of Rohingya refugees the following day in Bangladesh). On the other hand, given the ongoing humanitarian emergency in Rakhine, avoiding to name this specific minority has been seen as a nod to the Myanmar central government, at the expense of non-state formations. In that occasion the state gained authority and (indirect) legitimacy, while state-repelling people remained neglected, as if they were implicitly relegated behind the usual categories of armed groups, terrorists, refugees or immigrants. The salience of that absence resides in the overall process of mutual constitution between the Myanmar government and Myanmar’s “state-repelling” groups, a process that has been constantly ongoing since before the birth of the Union of Burma in 1948.

To conclude paraphrasing Scott, Myanmar arguably hosts one of the largest concentrations of state-repelling people on earth. Nevertheless, with the gradual occupation, co-optation and articulation of physical and social spaces and structures by central authorities, the only environment that seems left to them is that of illegality, often once again defined by and in mutual relation with the state.

Acknowledgements

Cover photo: Magdalena Roeseler (CC) 2016.

See respectively Burma News International, RCSS, Tatmadaw clashed four times in early January, 15 January 2018; and Burma News International, KNLA denies involvement in Mae Tha Waw clashes, 10 January 2018.

See also Burma News International, Ten Members of KKO surrender to BGF, 16 January 2018. ↩︎Burma News International, 21st Century Panglong Conference to be held only after holding public consultations – PPST, 16 January 2018. ↩︎

Scott, J.C. (2009), The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia, Yale: Yale University Press, p. 320. ↩︎

The term is taken from Scott, J.C. (2009), e.g. 128. ↩︎

Jolliffe, K. and Bainbridge, J. (2017), Security integration in Myanmar. Past experiences and future visions, Saferworld. ↩︎

Jolliffe, K. and Bainbridge, J. (2017), p. 4. ↩︎

Woods, K. (2016), Ceasefire Capitalism: Military-private Partnerships, Resource Concessions and Military State Building in the Burma-China Borderlands, in Sadan, M. ed., War and Peace in the Borderlands of Myanmar: The Kachin Ceasefire, 1994–2011, NIAS Studies in Asian Topics. ↩︎