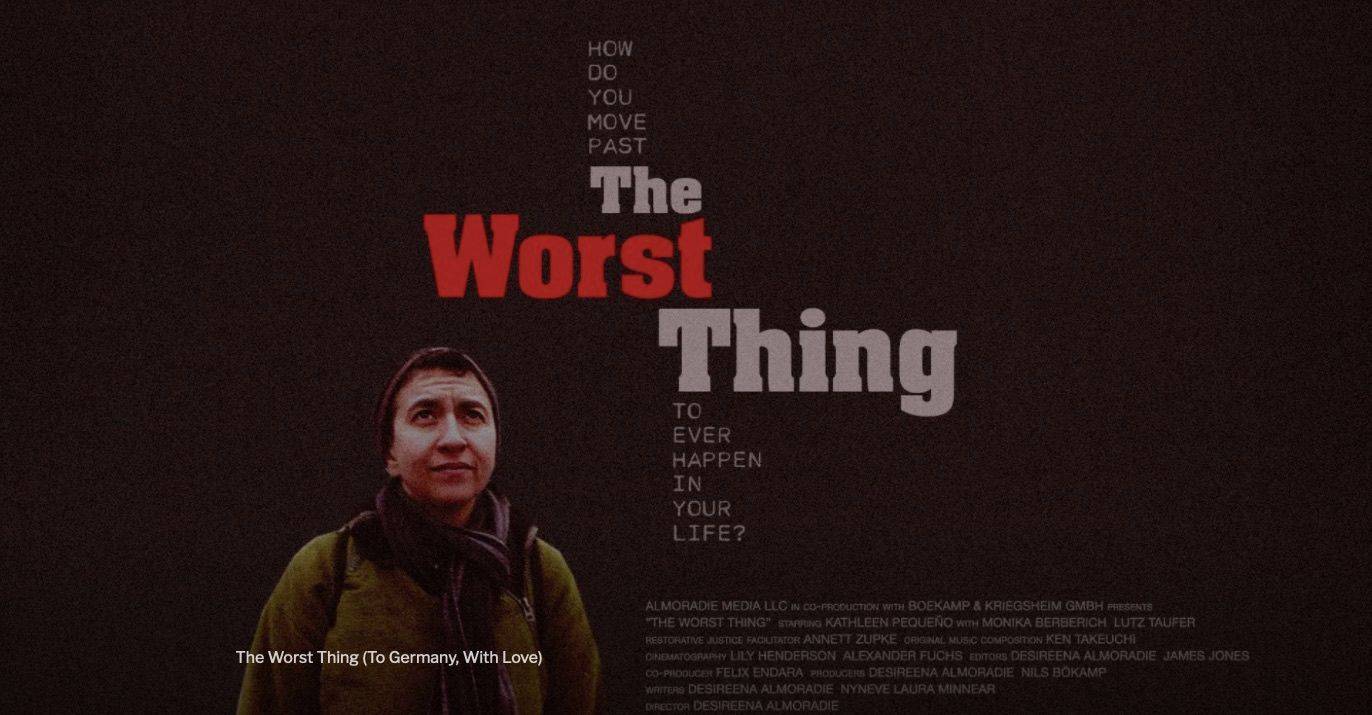

In November 2020 the European Forum for Restorative Justice organised an arts’ festival on the themes of justice, solidarity, and repair. Among the contributions of REstART was the documentary The Worst Thing (aka To Germany with Love). In 1985, a young American soldier called Edward Pimental was killed in Germany by the Red Army Faction (RAF). The documentary narrates his sister’s, Kathleen Pequeño, journey and quest for meaning, dialogue and healing as she sets out to engage with the RAF members who murdered her brother. The documentary, directed by filmmaker Desireena Almoradie, Kathleen’s high school friend, is at the same time a moving and profound ode to a long-life friendship between the two women.

[Spoiler alert: the piece reveals details about the plot]

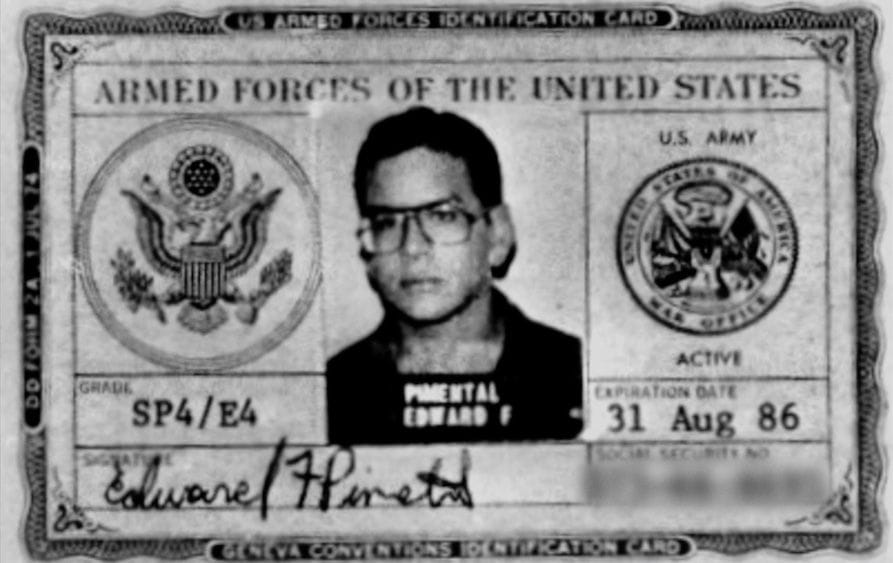

“We shot Edward Pimental, the air defense specialist”

Through the 1970s up to the early 1990s, RAF was responsible for a wave of terror attacks in Germany in which hundreds of people died and were injured. In the mid 1980s, 20 years old U.S. Army Specialist Edward Pimental was stationed at former Camp Pieri in Wiesbaden-Freudenberg, West Germany. On August 7th, 1985, he met RAF member Birgit Hogefeld at the Western Saloon nightclub in the city center. They leave the place together ending up at the nearby woods, where he was shot in the head. His ID is stolen and used the following day by RAF to drive a car full of explosives onto U.S. Rhein-Main Air Base in Frankfurt, killing two more Americans and injuring 23 others.

RAF and the French Action Directe armed group informed several news agencies that they took full responsibility for the action. Edward’s murder animated discussions among the far-left circles in West Germany since for the first time a person without major political status was deliberately killed. In the Communique from 25 August 1985, RAF writes that ‘the purpose of the action was to render a coordinating point of the US military machine – A CENTER FOR CARRYING OUT IMPERIALIST WAR – nonfunctional’ as part of the international struggle for liberation (emphasis in original). They continue in the Communique describing, situating, and legitimizing their action as part of a broader strategy for liberation. Referring to the soldiers who were there, RAF describes them as central actors of the imperialist war. Referring to Edward in particular, they write: “We shot Edward Pimental, the air defense specialist, who was in the army of his own free will, and in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRD) for the last three months, and who gave up his previous job because he hoped to get ahead more quickly and easily. We shot him because we needed his ID card to get onto the Air Base. For us, US soldiers in the FRG are not simultaneously villains and victims […] every soldier must understand that he will pay for waging war.”

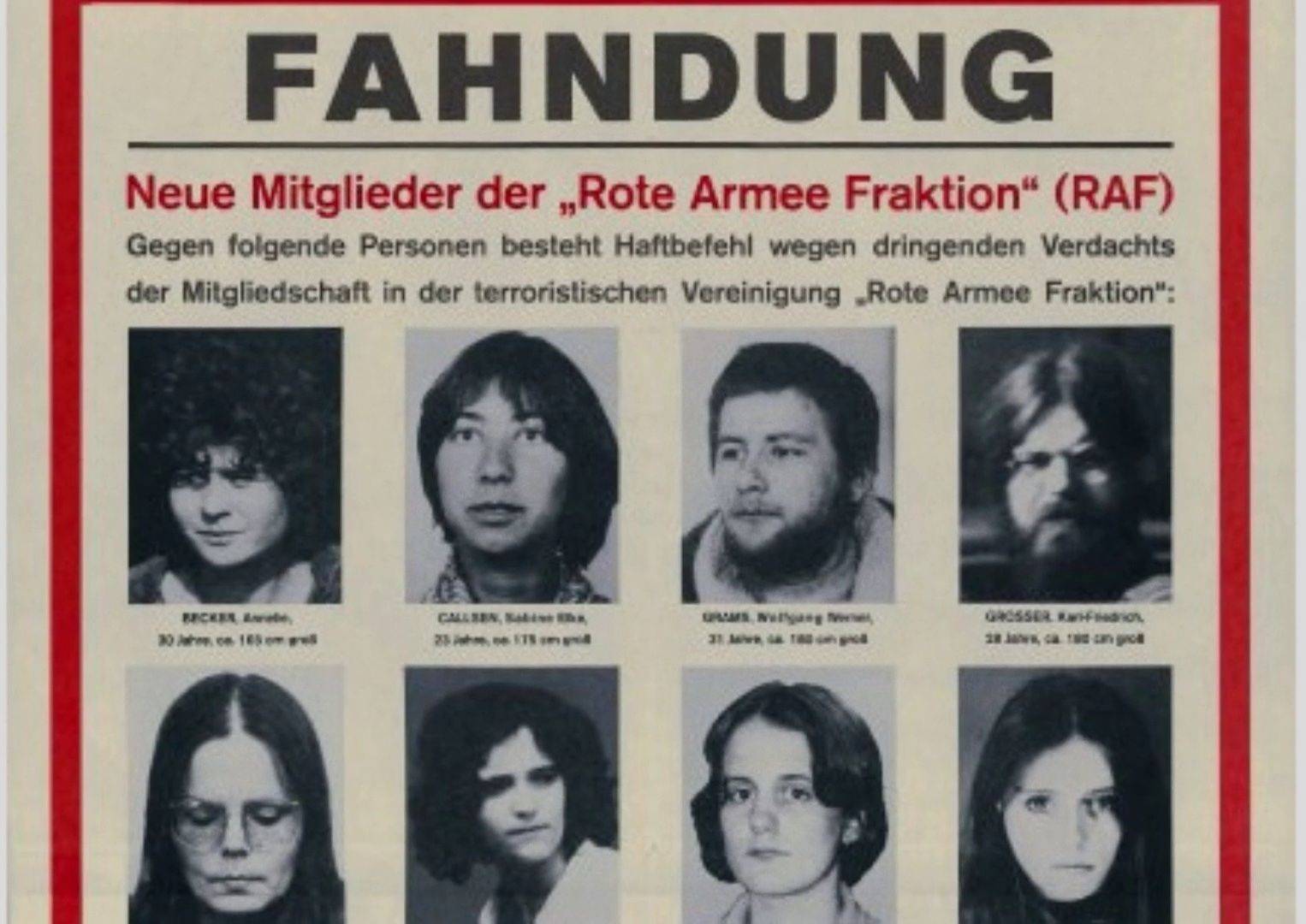

RAF was one of the many leftist groups born out of the protest movements of the 1960s, who built their active political stance against war and imperialism as a reaction to what they saw to be the political apathy of their compatriots that had given them Auschwitz. But they were not reacting only to apathy, their view was that their parents had been complicit in creating and maintaining Nazism. Through the years RAF’s actions became increasingly violent. In the 1980s, RAF was trying to rebuild itself, in the wake of the arrests of the so-called “second generation” leaders in 1982. In 1984, there was another important wave of arrests of several “third generation” members who had gone underground, but these did not include Birgit Hogefeld and Eva Haule, the ones held responsible for Edward’s death. They were eventually caught and convicted of participating in Edward’s murder and sentenced to life imprisonment but have been meanwhile released on parole. Eva Haule has not cooperated with the authorities and has chosen not to express remorse for RAF’s activities, whereas Birgit Hogefeld has dissociated herself with RAF and assumed personal responsibility for her crimes at the time. Eva Haule was released from prison in 2007 and Birgit Hogefeld was the last RAF member to be released from prison in 2011, whereas RAF itself was officially disbanded in 1998.

The quest for a different story

Kathleen was 15 when she heard of her brother’s death. The period after was extremely traumatic for her and the family. She describes it as being stuck within a time that didn’t flow, a time of perpetual and never-ending anger, pain, and hate. She wouldn’t talk about it with no one even though she could hardly think of anything else. The criminal justice response did little to heal her pain and that of her family. Victims and offenders go separate ways and that seemed counter to the sense of justice Kathleen felt would be right for her and to the world she wanted to live in. Those words are the ones Kathleen writes in the letter she sent to Birgit Hogefeld, asking her for a response as she kept searching for a different relation with former RAF members. How does one move past the worst thing that ever happened to them? It is that question that mobilises Kathleen’s journey. A need to move beyond the worst thing that has happened to her, but also towards encountering human beings who are more than the worst thing they have done. She is essentially looking for a different story, a story that is told differently, a story that ends up differently.

She shares her quest with the director, Desireena Almoradie, a high school friend of Kathleen's, and one of the few friends she had shared about Edward’s death, and other things that affected her. In 2011, they start working on the idea of documenting this quest and on working on ways to tell the story through the medium of a documentary. The documentary is nevertheless part of the healing journey itself, it does not only tell a story, it constitutes the story, affecting the quest. Desireena, respectful of her friend’s personal journey, is nevertheless not a distanced director, but a true companion and remains at the right distance and proximity from the pain and the search for meaning and healing. The documentary therefore just like the process of healing is patient and unrushed and the process of making it is long and hard.

Expanding response-ability

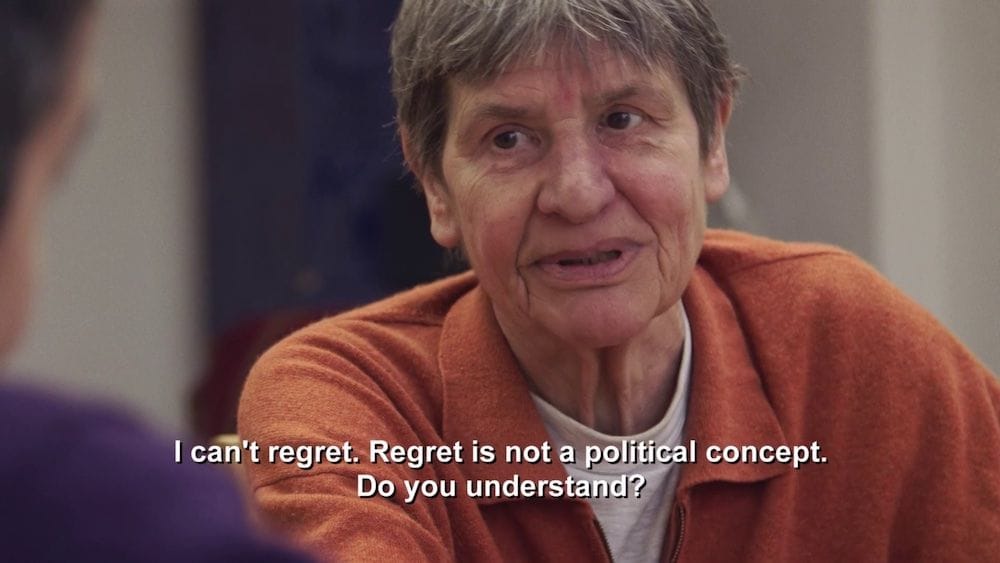

Kathleen starts her journey with strong convictions, which after every dialogic encounter get challenged in different ways by the people she enters into dialogue with. They question her motivations, beliefs, and expectations. As the story gets thicker and layered and keeps being populated with different voices and perspectives, Kathleen has to deal with different type of responses and non-responses to her quest, holding space, and being ready for what comes, painful discomfort included. Of the two people directly sentenced for their involvement in the murder of her brother, Birgit Hogefeld writes back to Kathleen, acknowledging her pain, but refusing to meet in person, whereas Eva Haule never responds. A point comes when Kathleen feels stuck in her search, until when they meet the mediator Annett Zupke, who encourages Kathleen’s quest and supports her contact and dialogues with former RAF members who were not directly involved in the murder of her brother and also with members of other similar groups. A few agree to meet Kathleen, and she has hard but fascinating encounters with four people in the documentary.

What the encounters show is the ways in which all the intentional human actions and gestures made towards each other are meant to elicit reflections but also further (re)actions. Each action in fact brings into life its own lines of actualization and possibilities and are thus open and unpredictable. Some important questions linger in our minds. Can a dialogue still exist if a dialogue is refused? Can a silence be a presence? Do all forms of communication communicate? Are different contexts of pains bridgeable? What the former RAF members and other former revolutionaries communicate to Kathleen is the ways in which ideology as a way of life can be a great wall, a cage, or even a disease. Some communicate to her their difficulty with the concept of regret, regret not being a political concept. For some that is a point that cannot be crossed, for others a cry for help. Some refuse to express themselves through emotions or share personal pains publicly, others welcome the possibility. Some puzzle as to how something as positive and justifiable as what they had started could turn out to be so ugly and cause so much pain to so many people, Kathleen included. Whatever the content and the communication form of the meetings, what is clearly taking place is expanding response-ability, everyone ability to respond to one another.

Human relations require an aptitude that is at the same time intellectual, affective, and moral. The documentary just like the quest remains open, and Kathleen continues creating or building her relationship with former RAF members, at the same time expanding and deepening the relationality with the past and with the future. Kathleen says ‘when murder happened my world got smaller, but now my world has gotten bigger’. As director Desireena says at the end of her documentary ‘with all her imperfections and human limitations, Kathleen continues to look for answers: how do we seek justice without perpetuating harm? How do we create a different story?’ Her own answer has been finding ways to tell a multidimensional story, one that will expand the response-ability of each of us.

Cover: still image from the documentary, original press coverage showing the aftermath of the terrorist attack at the U.S. Rhein-Main Air Base in Frankfurt, 1985.