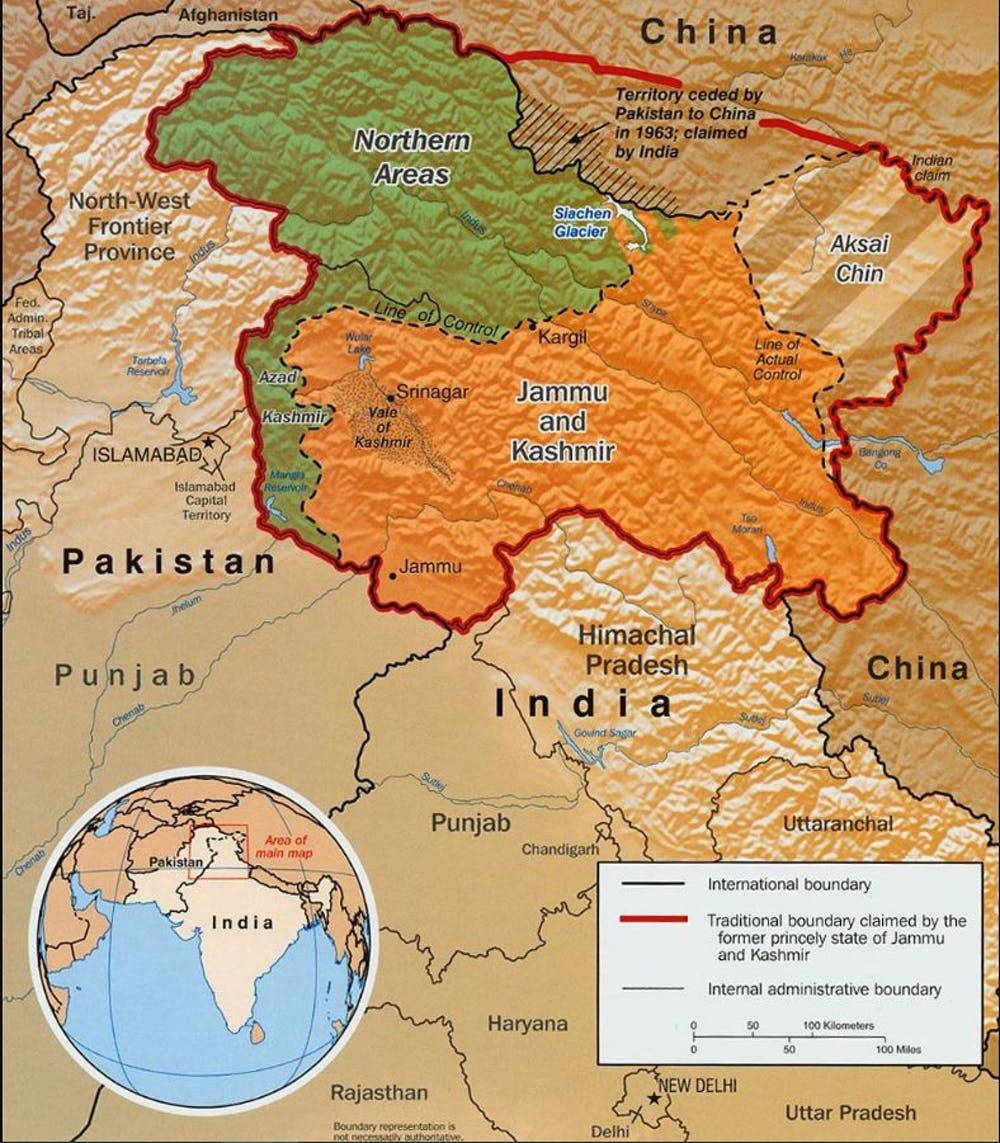

Last February India and Pakistan announced a ceasefire in the contested Kashmir for the first time in nearly twenty years. Although a potentially positive development, other ceasefires have been agreed upon in the decades after the last-minute partition of British India in 1947. The “Kashmir issue” has never been solved due to the region’s role as a political buffer zone wedged between three Nuclear Weapons states like India, Pakistan, and China and its strategic importance in political and economic terms. Its significance has legitimized four wars in 1948, 1965, 1971, 1999 and a series of asymmetric warfare operations in the 21st century. The northern and western sides of the region, Azad Kashmir and Gilgit and Baltistan, are formally administered by the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, while the southern and south-eastern Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) by India. Geographical and geopolitical divisions of Kashmir linked to the interests of India and Pakistan have forced its inhabitants to suffer from, and navigate through, various kinds of human rights abuses.

Both India and Pakistan have deployed violent means to secure their national interests in “their” respective administered territories. Although using different measures, in both areas blatant violations of human and political rights have been recorded. Perpetual conflict over the region presents the biggest challenge to the protection of Kashmiri rights.

It is important to be constantly reminded that Indian authorities call this region ‘’Pakistan occupied Kashmir’’ and vice versa, the Pakistani authorities call it ‘’Indian occupied Kashmir’’: a remark that immediately underscores the contested nature of an area literally on the edge of the state. The Indian and Pakistani administered portions are divided by a “line of control” (LoC) agreed in 1972, although neither country recognizes it as a de facto international boundary. The conflict over the region of Kashmir is portrayed by India’s will to confirm the act of accession and Pakistan’s will to consider the region its own natural extension. That is why the UN Security Council, through different measures, tried to avoid a dangerous escalation, forming the UN Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP – still active to date) in order to monitor developments pertaining the strict observance of the 1971 ceasefire, to the extent possible, and to report thereon to the Secretary General. The end of the dispute, however, is still far away, since both India and Pakistan have often shown prone to redirect national political, social, and religious tensions towards external enemies.

Over the last few years, Indian-Administered Kashmir registered high rates of human right violations linked to extrajudicial killings and excessive use of force by Indian security forces, rarely subject to investigation and prosecution. Since 2019 the Indian government revoked Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, which originally granted special status to Jammu and Kashmir. Such measure eroded its political autonomy by integrating it fully into India and are part of the Hindu-nationalist agenda of the Narendra Modi administration, with increased influence of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh's fascistic militancy within the Bharatiya Janata Party. The act was accompanied by the cutting off of communication lines in the Kashmir Valley, the imposition of curfew which effectively muted any reaction in the region, and a growing deployment of security forces to confront possible uprisings. Protests erupted for such rights’ abuses and the use of pellet-firing shotguns to manage crowds resulted in deaths and injuries. ‘’Cordon and search operations’’ tactics are accompanied by physical intimidation, assault, invasion of privacy, destruction of property, and sexual abuses. Collective punishment and forms of arbitrary detention are employed to target protesters, political dissidents, and other civil society actors including children under 18, through the Kashmir Public Safety Act 1978 (PSA). Cases have been reported of detainees transferred outside Jammu and Kashmir, in turn stripping them of the possibility to meet families and seek legal assistance. This is especially true for Kashmiri Muslims, who are treated like “terror suspects’’. On top of that, the area is characterised by strict restrictions of freedom of expression via censorship, attacks on press groups and activists, and internet shutdowns. Different measures have also restricted freedom of assembly and association targeting different religious-political organizations through arrests. Lastly, serious human rights abuses such as kidnappings, beheadings, extortions, sexual violence and killings are being committed also by non-state armed groups operating in Jammu and Kashmir, such as militants advocating for a shift towards Pakistan.

On the other hand, Pakistan-Administered Kashmir’s constitutional and legal structures represent a threat for civil and human rights of local populations. Azad Kashmir’s 13th amendment to its Interim Constitution (2018) altered Kashmir Council’s status to an advisory role, transferring its powers to the Prime Minister of Pakistan. The amendment codified discriminatory provisions targeting minorities and restricting their freedom of religion. Such reforms gave rise to protests carried out by political parties, pro-independence groups, and civil society organizations demanding full representation and democratic rights. Such measures restrict citizens’ rights to criticize the region’s accession to Pakistan. In Azad Kashmir, the region’s electoral law disqualifies those not solemnly sharing the ideology of state’s accession to Pakistan. Similar restrictions are to be found in Gilgit-Baltistan Governance reforms, denying its citizens the right to become chief judge of the Supreme Appellate Court and to express concern over internal security. Freedom of expression is denied to members of nationalist and pro-independence political parties since they (and their families and children) face different forms of threats and arrests by local authorities and intelligence agencies. Similar threats are faced by media houses, which very often decide to self-censor to avoid persecutions from security agencies and not to lose government advertisements. The same treatment is directed to journalists not conforming to mainstream discourses in favour of Pakistan’s accession and business coming with it. For example, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project in Gilgit-Baltistan triggered a sense of indignation among citizens and civil society groups due to its environmental, economic and demographic impacts on local communities and natural resources. Increasing security presence, army checkpoints, intimidation and repression of protests are the most widespread measures used to suppress local resentments. The Anti-Terrorism Act 1997 is widely used to target political activists, human rights defenders, dissidents and students arresting them without warrant, often bringing to torture to extract information. Lastly, cases of enforced disappearances have emerged in recent years as a tool used by Pakistani intelligence agencies violating right to life, prohibition of torture and degrading treatments.

Kashmir’s stalemate seems to be undying, as debated by reports of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). The report highlighted numerous human rights violations and patterns of impunity in Indian-Administered Kashmir and significant human rights concerns in Pakistan-Administered Kashmir. India and Pakistan should act on the recommendations of the United Nations human rights office (such as the respect of international human rights law obligations) to protect basic rights in the contested region of Kashmir. Responses were different: India dismissed the report “fallacious, tendentious and politically motivated” and that ignored “the core issue of cross-border terrorism;” Pakistan welcomed the report but requested that sections be removed or amended in which the information was “not specific to Pakistan-Administered Kashmir but were general human rights concerns affecting all of Pakistan”. There is hope that the India-Pakistan ceasefire deal would lead to a broader settlement of issues between India and Pakistan, like the serious human rights abuses in the region. However, the situation in Kashmir is embedding the region in a perpetual security dilemma directed by the two states at the cost of a population which has been continuously showing its resilience during the last years. Nevertheless, resilience is not endless like the security trap in which Kashmiri are stuck appears to be. While state authorities debate the security of the border, violations of local residents’ rights remain a constant trait of everyday life in these contested regions.

All photographs (CC) by lecercle, "No time for love – Srinagar", 2009.