Explorations on justice through New Media Documentaries.

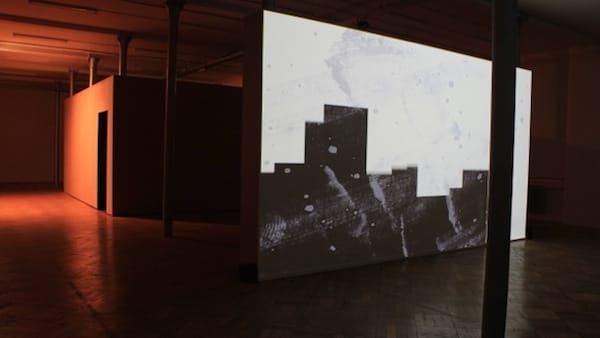

The exhibition Convictions brought together at STUK cultural centre in Leuven, Belgium (26.09 – 17.11 2013), four projects by the Californian digital and media artist Sharon Daniel from the University of California in Santa Cruz: Public Secrets, Blood Sugar, Undoing Time and Inside The Distance. Daniel’s works introduce marginal and often silenced voices and present alternative visions, enabling public engagement with questions of social justice across social, racial, political and economic boundaries.

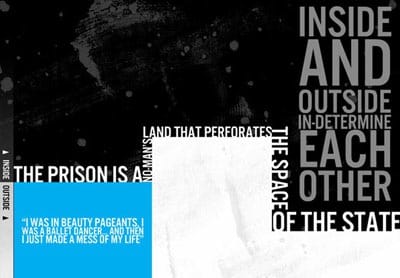

Public Secrets is a New Media Documentary (NMD) that explores the expansion of the prison system. The artist has visited the Central California Women’s Facility on behalf of a human rights organisation in order to document her conversations with incarcerated women and bring their voices to public awareness. The NMD provides an interactive interface to an audio archive of hundreds of statements made by current and former female prisoners, which reveal the many secret injustices perpetrated by the state against its most vulnerable citizens. Visitors navigate a multi-vocal narrative that links individual testimony, public evidence and social theory, in order to challenge the assumption that imprisonment provides a solution to social problems.

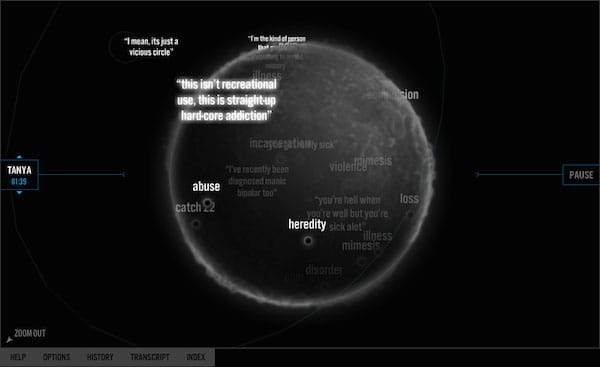

Blood Sugar is an interactive interface to an online audio archive of conversations recorded with current and former injection drug users. Blood Sugar enhances awareness of the relation between poverty, addiction, and HIV transmission, and the social and political implication of the ‘war on drugs’.

In Undoing Time Sharon Daniel is taking products produced in prison factories and inscribing them with quotes from interviews in which incarcerated men and women describe their encounters with the criminal justice system and discuss what it means to “do time” in California’s state prisons.

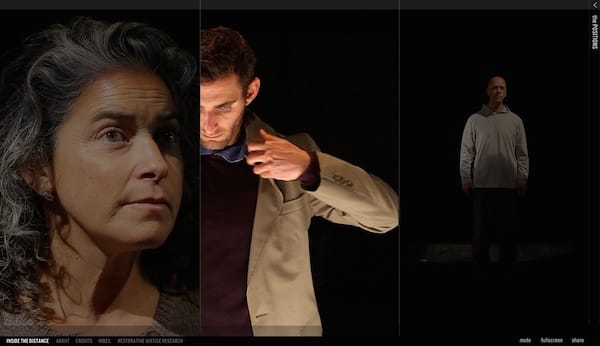

Inside the Distance is an interactive NMD on restorative justice, an alternative to the criminal justice system, which conceives of crime as a concrete disruption of and harm to human relations. The work examines the practice of mediation in Belgium, by bringing together interviews with victims, offenders, mediators, prison directors, and researchers.

These works manifest Daniel’s fully engaged and critical understanding of the prison-industrial complex, criminal justice system, and theories of justice and punishment. What characterises her work is the belief that complex sites of socio-political experience are best examined by creating a context for multiple perspectives and engaging public participation. The interactive interfaces that are typical of her work allow viewers to find their way through a difficult terrain, become immersed in it, and have a transformative experience.

Art as an affective, performative, and political site

The works of Sharon Daniel introduce marginal and often silenced voices and present alternative visions, enabling public engagement with questions of social justice across social, racial, political and economic boundaries. For her, politics becomes a particular kind of speech situation – when those who are excluded from the political order or included in only a subordinate way stand up and speak for themselves. There is a relation to the political and the affect in this understanding. To draw from Rancière, critical art is setting out the encounter, and possibly the clash of heterogeneous elements that is supposed to provoke a break in our perception, to disclose some secret connection of things hidden behind everyday reality. Through this form of practice, she appropriates Ranciere’s formulation of politics and transposes it into the register of art, thus materialising a space of ‘dissensus’ – not a critique or a protest, but a confrontation of the status quo with what it does not admit, what is invisible, inaudible and othered. Sharon Daniel often speaks of herself in relation to her work practice as a ‘context-provider’ (as opposed to a content-provider). She provides the means, or tools that will induce others to speak for themselves, and the context in which they may be heard.

In the Affectivist Manifesto Brian Holmes writes that ‘world society is the theater of affectivist art’. According to this thesis, instead of proposing concrete political change, the profound role of the artworks lies in their potential to increase an understanding of the possibility of change. Using imagination as an artistic device, an artist helps thus produce a precondition for politically and socially transformative effects. Only through imagination does one have the freedom to picture otherwise, of thinking ‘what could be’ and not only ‘what is’. Imagining the precariousness of all people and one’s own responsibility and role within such processes, Daniel uses strategies of affect to install a thought-provoking discourse on the possibility and impossibility of justice. Daniel urges the viewer into re-enchantment with the world and with the subject matter, into a hermeneutical dwelling into the research field, into ‘response-ability’. Waking up the ‘response-ability’ in her audience by offering them spaces of imagination of ‘untold secrets’ through ‘unheard voices’, and alternative paths that can be taken is key to her work.

The other element which makes Daniel’s work decisively political is her creation of a collective site of experience. For each project she collects the statements and the perspectives of a fairly large number of people who share a particular experience: for example, incarcerated women (in Public Secrets), or injection drug users (in Blood Sugar), or crime victims/offenders (in Inside the Distance). She provides a context that allows their voices to be heard both individually and as a collective voice. Her strategy involves addressing an issue, context or marginalised community as a ‘site’ (or scene or field) rather than through a story or individual narrative. She collects significant amount of direct testimony from a ‘site’ and then she designs an interface structured in a manner that will both circumscribe and describe this ‘site’ of socio-economic and political experience as articulated by the participants. There exists a productive tension between the particularities of individual histories that are the most compelling aspects of narrative persuasion, and the force capacity of the collective voice. Daniel argues that where one voice, an individual story, is intended to stand in for a class of subjects, there is a dangerous and disabling tendency to identify the subject as a case of a tragically flawed character or unusually unfortunate victim of aberrant injustice – rather than one among many affected by structural inequality. When multiple voices speak, in a manner that is intimate and personal, collective and performative, from the same experience of marginalisation, the scale and scope of injustice is forcefully revealed.

Visitors to Public Secrets, Blood Sugar, and other works of Sharon Daniel navigate a multi-vocal narrative that brings the voices of her subjects into dialogue with other legal, political and social theorists such as Giorgio Agamben, Michael Taussig, Walter Benjamin, Fredric Jameson, Jacque Rancière, Catherine MacKinnon, and Angela Davis. For Daniel all of their voices emerge out of a shared ethos and converge in critical resistance. Taken together, the recorded interviews or conversations, the information and interaction design and theoretical framework, materialise the Rancièreian ‘political’, creating a space of ‘dissensus’ both for participants and for viewers – one that introduces new subjects into the field of perception. By providing a context, a political site, a performative space, and an affective frame, Daniel, offers a space for intersubjective ‘response-ability’. Her work allows for persons – who otherwise would have remained invisible – to become visible.