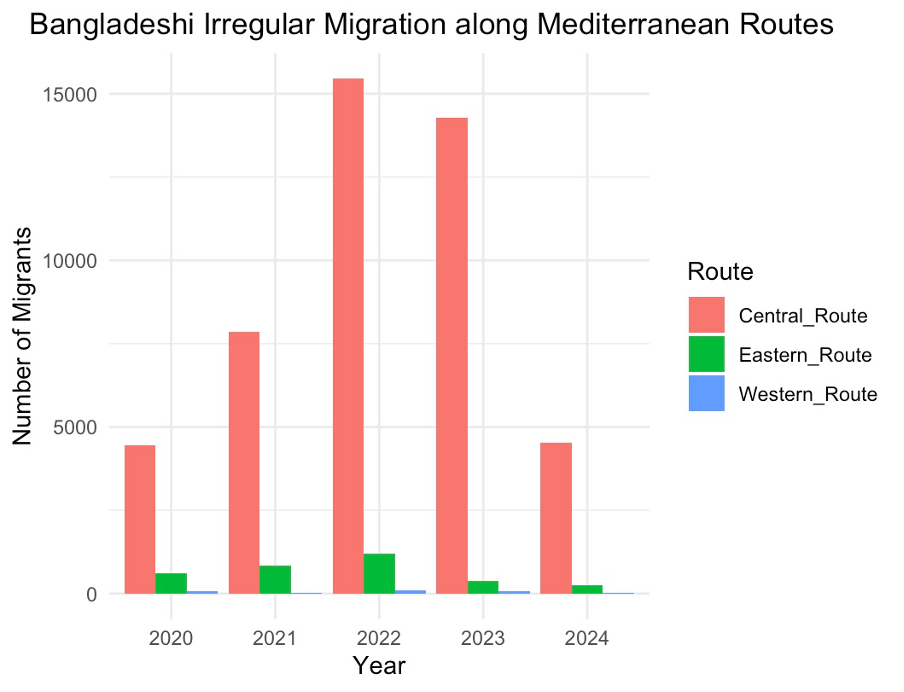

In 2024, EU statistics revealed a concerning trend: up until May, 4,537 Bangladeshi individuals had irregularly crossed the central Mediterranean route, marking the highest number of migrants from a single nationality using this route. How to make sense of this inflow? Is Bangladesh in the midst of a war crisis, ethnic cleansing, or any conflict? In spite of the ongoing political crisis and clashes between opposition parties and the government with economic instability, the direct answer should be negative. Traditionally, Bangladesh is known for natural disasters, but new phenomena have emerged, especially in the last twenty-five years, impacting the origin and destination of international migration flows. Bangladesh is a small piece of land around half of Italy's land size with a 174 million population, around 17 million people living abroad, including eighty percent in the Middle East. According to recent studies, the prime causes of migration are political instability, climate change, and unemployment, especially of the unskilled labor force. The middle class and mostly educated people are predominant among those who take up the challenge of migrating abroad.

Bangladeshi irregularly migrating to Europe use all three Mediterranean routes – central, western, and eastern – with the central route via Libya and/or Tunisia being the most popular, especially among those who resided for a time in the Middle East. While, until the 90s, the eastern route via Turkey and Greece was more commonly used, the central route's growing popularity is arguably due to the abundance of information, networks, and connections with Italy, which is home to the most significant number of Bangladeshis in the Schengen area. Typically, migrants first arrive in Libya or Tunisia by plane from Bangladesh or MENA (Middle East and North Africa) countries as tourists or with a work permit; once in North Africa, they wait for optimal conditions, such as good weather and a sufficient number of people ready to embark on a sea crossing. During this time, they also coordinate with other European facilitators to the final destination. From Libya, migration flows most frequently lead to Italy, followed by Greece, Spain, and other European countries, depending on the available information, networks, and intermediaries.

The key players in migration journeys include facilitators, such as friends and relatives living in Mediterranean countries, as well as Bangladesh-based brokers of manpower agencies. Manpower agencies are key actors in Bangladeshi irregular migration, as they recruit both skilled and unskilled workers to send abroad. Earlier on, these agencies focused on recruiting labour mainly destined for Middle Eastern countries, but have since expanded their operations to other countries. Each agency has unofficial agents throughout Bangladesh who work for them and have strong social connections. Locally known as Dalal, these local facilitators play a crucial role as initial intermediaries and negotiators, providing essential information and establishing trust while offering reasonable prices compared to legal migration avenues from Bangladesh to European destinations, including costs for transfer to destination countries, documentation, accommodation, and jobs.

Smugglers, on the other hand, act as secondary helpers, although smugglers, manpower agencies, human traffickers, and brokers can all be intertwined since the same person can play different roles. Secondary helpers are intermediaries based in MENA countries who have connections with facilitators in both the origin and destination countries. Regarding the latter, facilitators based in the EU include previous irregular migrants, human traffickers, smugglers, and sometimes even security forces. They typically provide migrants with accommodation, documents, and jobs in the EU. At times, former migrants or local manpower agencies manage intercontinental smuggling operations by leveraging their connections with smugglers and traffickers.

Aspirant migrants from Bangladesh may first travel to North African countries, especially Libya and Tunisia, by plane with a visa before handing over to international smugglers or facilitators. Alternatively, Bangladeshi migrants already present in the MENA region use their connections to directly or indirectly engage with smugglers and human traffickers, negotiating prices and conditions for their journey to Europe. This migration process is lengthy, often taking six to twenty-four months to reach the destination country. Negotiations are complex, involving multiple actors and numerous smugglers, including those who are locally rooted and those who are internationally connected. Migrants may be handed over to various smugglers across different countries, highlighting both professional commitments and disagreements within the smuggling network.

As a result, many migrants may endure prolonged stays and disrupted journeys, including extrajudicial detention in small, overcrowded rooms, facing beatings, demands for extra money, sexual harassment, organ damage, slavery, and transfers to human traffickers. Migrants may also face forced disappearance. Families then reach out to the original local middleman, who typically hides until the situation normalizes or enforcement agencies lose interest. These networks are vast and sometimes include complicit government officials, such as airport authorities and local police, who benefit from and engage in these illicit activities.

It is alarming to see how deeply rooted smuggling and human trafficking are in Bangladeshi society, with connections to political power. A recent incident in Kuwait resulted in a member of parliament receiving a lifetime jail sentence for human trafficking and money laundering. It is, in fact, likely that without support from the political system these illegal activities would be unable to thrive. This raises serious concerns about the influence of money in elections, as it is quite impossible to win an election without money. From this perspective, human smugglers or traffickers are arguably mixed with politics, and they often compete in elections and run for government office, thereby highlighting the complexities of the situation.

The cost of irregular migration can vary significantly based on the routes taken, the number of intermediaries involved, how many services are included, and the duration of the journey. On average, it ranges from 6,000 to 10,000 euros, including the costs such as plane fare, securing accommodation, documents, and a job in Europe, boat fare, and fees for smugglers and/or human traffickers, but this can increase if additional days are needed; additional numbers of 'game'[1] are needed or if migrants fall into the hands of human traffickers. Some individuals end up paying as much as 15,000 euros because of higher ransom demands by human traffickers. These traffickers mainly operate in the MENA transit countries near the Mediterranean Sea, and they have direct connections with local Bangladeshi facilitators. At the same time, local sources suggest that manpower agencies may charge and other facilitators may charge as little as 6-8,000 euros in the case of irregular migration schemes.

This raises the question of how migrant families can manage to gather such substantial sums. Primarily, one needs to stress that these migrants traveling across continents often come from middle-class backgrounds and resort to various means to fund their journeys. They often sell their property, deplete lifelong savings, borrow money from friends and family, and take out loans from microcredit agencies or banks. In many cases, selling one’s home becomes a last resort in the pursuit of a much-longed-for better life in Europe.

Observations also suggest that many migrants find paying in installments to be a practical solution that eases their immediate financial burden, it also logical to pay by installment for smugglers or human traffickers for crossing every border. This is especially true since selling property can be a lengthy process that requires finding willing buyers. The youth that is plagued by social and physical insecurity finds little hope in Bangladesh, with little legal information and legal avenues to immigrate to the EU, which clearly influences the cost-benefit ratio of one’s decision to leave in spite of the dangers along the Mediterranean migration route. These are widely known and somehow factored in by migrants before departure. Equipped with information about life in Italy, Bangladeshi migrants are discouraged from investing in their homeland and are driven by the aspiration for a better future in Europe.

The journey of migrants is not always successful, though; many face failure, death, or become victims of violence along the migration routes. Bangladeshis lack a tracking system or support services from the government or NGOs for families of irregular migrants who experience tragedy. Families often seek help from government officials or those with social recognition and political connections, but this is not always effective. Officials often ask for bribes, adding to the burdens of already struggling families. Addressing this type of incident or death often involves compensation between local facilitators and migrant families with lumpsum money, but the process is biased in favor of local facilitators or agents who have significant influence and power in society. Furthermore, aspiring migrants, who usually are the primary breadwinners, may leave their families to bear the tragic consequences of a failed migratory project, which can lead those who stayed behind to malnutrition, child labor, forced urban migration, school dropouts, family crises, and divorce. Many families have been pushed to the brink, with some members even attempting suicide. It’s a vicious cycle: if you fail to enter Europe successfully, you are trapped in a relentless cycle of poverty and misfortune.

In the current political environment, it is not easy to see any optimism. The manipulation that has characterized the last three national elections in Bangladesh has fostered insecurity among the middle class and opposition parties, while political clientelism fuels corruption and an economic crisis. With political and economic elites siphoning money from banks and stashing it in offshore accounts, the future looks bleak. This situation may drive more people to seek dangerous Mediterranean routes, resulting in a rise in border deaths and casualties.

Notes

[1] Smugglers or human traffickers use the ‘game’ word to explain the attempt to cross the borders or sea.