by Antonina Kseinova, Federica Pizzo, Felix Jahn.

The Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies (SSSA) and the Italian Standing Group of International Relations (SGRI) welcomed the new year with the organization of two roundtables on an issue that is once more proving to be coming back to the center stage of International Relations: geopolitics.

Classical Geopolitics, which conceptualized politics as a geographically induced realist practice of states and nations competing for power and survival was never part of the IR discipline as such. However, it was a prominent way of thinking in international politics in the first half of the 20th century, with Ratzel's Lebensraum, Mackinder's Heartland, or Spykman's Rimland. The post-Cold War containment policy also illustrated the enduring influence of geopolitical doctrines among decision-makers. Nevertheless, the study of this phenomenon declined progressively and eventually was replaced by a new, critical approach in the 1990s, which focuses on the spatiality of power across social science and came to be known as the spatial turn in IR. By the late 1990s, Critical Geopolitics, as coined by Simon Dalby, had gained special attention within political geography. It highlighted the ways in which classical geopolitics was informed by fixed and simplistic geographical assumptions about the inside and outside, confining the thinking about states into a territorial trap. In contrast, critical geopolitics offered new lenses to review geopolitics as a social (re-)production of cultural and political practices present in a geographical context, thereby contributing to understanding a world where the rise of non-state actors, transnationalism, and multilevel governance gained momentum.

In recent years, however, multiple references to geopolitics have started again to surface. US foreign policy vis-à-vis China largely reminds of the categories of containment, the conclusion of the military alliance AUKUS being the latest example. In Europe, this era of perceived strategic competition and complexifying security threats has also left a mark on the EU, responding with the idea of a “geopolitical Europe”. For other actors, the use of geopolitical images has also found a prominent entry into their policies, with Turkey’s ‘Mavi Vatan’ or the Russian concept of ‘Eurasia’ being just two examples. These examples suggest a renewed diffusion of geopolitics-inspired thinking among today’s decision-makers.

Against this background, the conference was divided into two panels. While the first focused on the return of geopolitics and the study of IR, the second one dealt with geopolitics and Italy.

Roundtable 1: The “return of geopolitics” and the study of International Relations

The conference was opened by Stefano Guzzini (Uppsala University, Danish Institute for International Studies), who started by highlighting the two main premises of geopolitics. Firstly, the return of geopolitics in the 1990s was not connected to territorial conflicts but was rather the result of an identity crisis of the security imaginary of certain countries in the aftermath of the Cold War, as “people were afraid of peace”. Secondly, geopolitics as such is not a strategy, but a theory, meaning that its use as an approach to shaping a foreign policy would be misleading. Its use in the public discourse is predominately informed by a problematic social-Darwinist understanding of international politics. Overall, references to geopolitics are either banal, in as much as no one denies that geography matters in international politics, or plainly wrong if claims of sheer geographical determinism are made.

The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic demonstrated once more that in a highly interconnected world communications and links are paramount. For Simon Dalby (Balsillie School of International Affairs) this clearly shows that new context, new danger and simply operating geopolitics within state boundaries and state rivalries is obscuring. Dalby also highlighted the parallels between the climate crisis and the Cold War. The self-destructive capability of nuclear weapons is now akin to the burning of fossil fuels, demanding equal efforts of governance and restraint as back then with arms control. Commonly accepted geographical assumptions in our political and security thinking – such as the misleading inside-outside dichotomy – are coming back, and therefore the utmost task of Critical Geopolitics is to tackle these wrongly “taken-for-granted” concepts.

This worrying reliance on geopolitical “taken-for-granted” images has not spared the EU either, which over the past decade has responded to external challenges by fostering geopolitically-inspired discourses and policies. In this regard, Luiza Bialasiewicz (University of Amsterdam) pointed out that with the EU’s Global Strategy, Juncker’s “everything is geopolitical”, or Von der Leyen’s “Geopolitical Commission”, has reasserted to hard power imagery in order to find reassurance in a changing reality, however neglecting the fact that such language creates insecurities itself. This is particularly evident with the inflated use of the blurred concept of “strategic sovereignty”, which contributes to constructing a confrontational fiction whereby the EU should reclaim its sovereignty from other actors, such as China or the US. As such, contesting this dangerous fixation on threats is - and in that Bialasiewicz very much agreed with Dalby and Guzzini (“its mere mission creep”) – one of the most urgent tasks of critical scholars.

Roundtable 2: Italy and Geopolitics

The second day of the conference narrowed the case on geopolitics to the Italian context. Designed as a debate between scholars, analysts and journalists, the participants discussed the popular and academic role of geopolitics in Italy. The panel’s chair, Emidio Diodato (University for Foreigners of Perugia), opened the debate referring to the 18th century poet Vittorio Alfieri, whose autobiography was described as an early example of making a relationship between international and geopolitical relations, making a full circle to the present phase with the current regain of interest in geopolitics in Italy.

Andrea Ruggeri (University of Oxford) reproached the fact that in Italy international politics is frequently associated with geopolitics; however, it is impossible to use geopolitics as the only tool to understand and study international politics. In combination with its deterministic nature, geopolitics is problematic in its leaving behind the important aspects of norms, values, and international law. Additionally, geopolitics puts hierarchies in the foreground (racing for hegemony as the engine for international competition) excluding cooperative relations. One needs to look at geopolitics with a critical approach, considering the variety of individual determinations, interests and ideas. Otherwise, this bears the risk of falling again into a territorial trap (John Agnew).

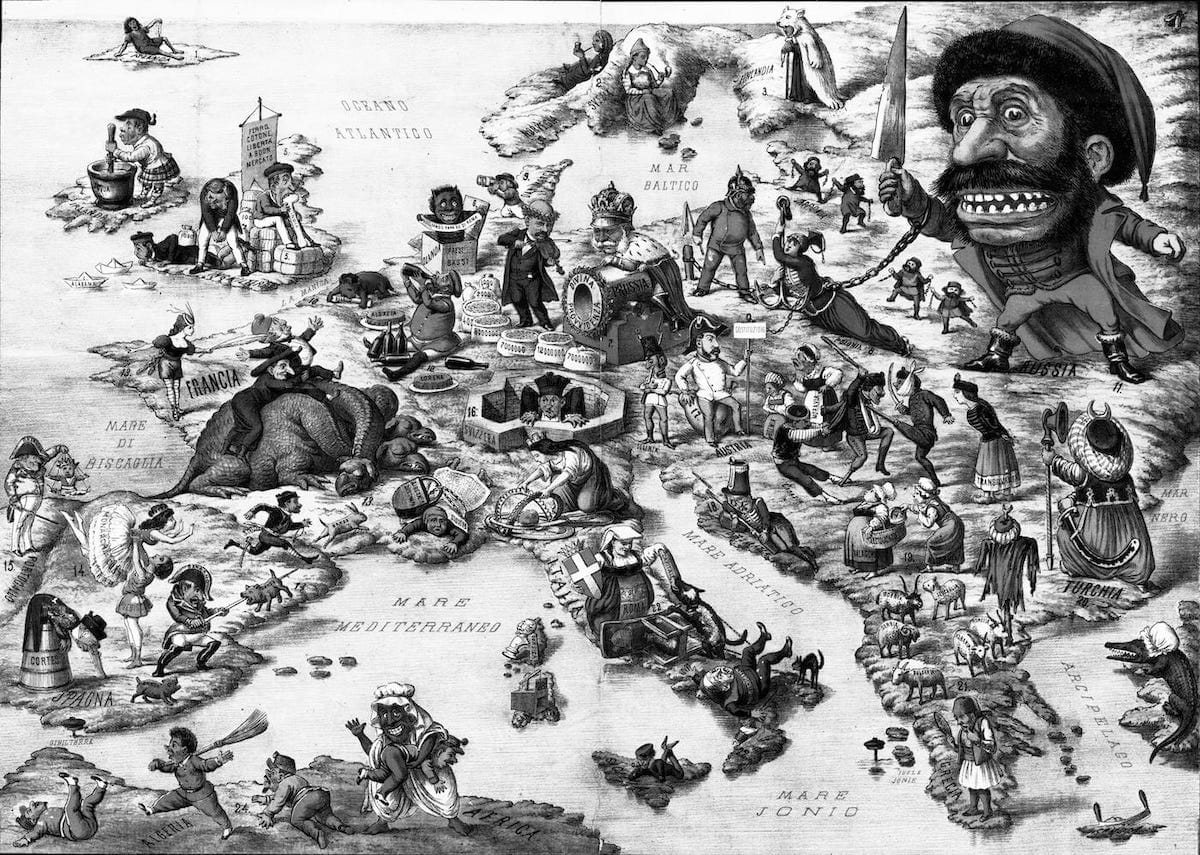

Sonia Lucarelli (University of Bologna) recalled the origins of Limes magazine in the 1990s. She pointed out that, instead of building on theoretical advances in IR, the magazine privileged a simplistic discussion of international politics, extensively relying on impactful yet often misleading maps. She also emphasized the difficult stance of poststructuralist thinking: its marginalization stems from the hegemony of realist and liberalist approaches to IR in the Italian academia, contributing to the current gap between a poorly-educated public debate on geopolitics, and a self-referential critical academic discussion.

Edoardo Boria (University La Sapienza Roma, Limes) stressed the concern towards scholars who, coming from Carl Schmitt, arrived at geopolitics with a cut-through of disciplines that subdues geopolitics as a separate field of study. Geopolitics is not the right-hand field of IR, but should be seen as an accessory tool to investigate international politics, since it takes into consideration a differentiation of spaces (territorial, hybrid, and financial). Answering to the allegations of determinism, Boria argued that the space of geopolitics is not a physical but a relational construct, meaning that it can always be reconfigured due to the emergence of new actors, frames and technologies, making it neither static nor immutable.

Drawing on a journalistic background, Azzurra Meringolo (RAI, WIIS Italia) argued that the notion of geopolitics is mainly embedded into an agenda-setting struggle, that is the question of what news is to be reported in a specific context, and how. As such, it is a question of language. As different narratives and framings of international politics are competing for visibility, she stressed that the language of geopolitics may be less precise, but it is also more expressive and better suited to illustrating the dynamics of certain events to the wider public, through the use of impactful maps.

Federico Petroni (Limes School) argued in favor of geopolitics by pointing to its value in displaying the dynamic of conflicts. In Petroni’s view, geopolitics does not amount to mere geographical determinism. Instead, it is a comprehensive approach that enables the study of the political projects of collective actors as they are projected on a certain space, and the reactions they trigger. From this perspective, geopolitics’ contribution to the analysis of international politics is twofold. Firstly, it elaborates on the unintentional consequences of political choices from a historical perspective. Secondly, it provides a practice-oriented tool used by policy-makers to understand conflicts.

The results of the discussion covering journalistic, academic, linguistic, and critical perspectives on the study and use of geopolitics among the wider public have proven to be timely and fruitful, but also one demanding further research and debate. In view of that, host Francesco Strazzari (Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna Pisa) concluded the roundtable with the intention of organizing further conferences to sustain the conversation among all stakeholders.

The authors are students of the International Security Studies (MISS) jointly organized by the Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies (Pisa) and the University of Trento.

Cover image: “Geo-political Europe, goose-eye view", satyrical map, 1871 circa, Wikimedia Commons.