As the Myanmar peace process initiated by Thein Sein’s government in 2011 moves into its eighth year, two main contentious issues have always been at its core. First, there is the constitutional and institutional framework of the country and the question of federalism. Second, what in the 2015 National Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) came to be termed as “security reintegration”i – namely the process of disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) of armed non-state actors and security sector reform (SSR).

If on paper the two might seem to belong to different spheres – like peace and war, political and military matters – federalism and DDR-SSR are deeply interconnected and crucial in drawing the future configurations of power, authority, and sovereignty. While the positions of the two main camps seem incompatible, any step forward will probably require middle-ground solutions and flexible arrangements on these two topics.

The NCA has been signed by ten out of twenty-one Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) and many of the most powerful groups still remain outside it. Basically, a main line of division has emerged between EAOs based in the south/southeast of the country and EAOs based in the north/northeast. The Tatmadaw and the government by and large want the issue of federalism to be dealt with after the signing of the NCA peace accord and inside the parliament, within the framework of the institutional and political architecture based on the 2008 military-drafted constitution. This at least in principle, although in late January the National League for Democracy (NLD) has launched an attempt to modify the charter by forming a joint committee to evaluate constitutional amendments. Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) on their part lament the lack of representativity and autonomy of the legislative body, considering it an extension of the previous military regime, and understand the NCA as a politico-military control strategy enacted by the Tatmadaw. In fact, EAOs that have not signed the NCA are not allowed to take part to the Union Peace Conferences where political dialogue is supposed to take place on the basis of the principles enshrined in the ceasefire. Such a condition has proved problematic for both signatory and non-signatory EAOs since those principles are underpinned by the three-fold mission of the Tatmadaw aimed to the: “non-disintegration of the union, non-disintegration of national solidarity and perpetuation of national sovereignty.” In other words, the political directions of the peace process have been enshrined by the ceasefire before any real “nationwide” truce involving all the parties on the ground was signed.

On the matter of DDR-SSR, the Tatmadaw and the government require EAOs to disarm as a next step in the implementation of the NCA and to come into “the legal fold” within the current security sector structure. Instead, EAOs are unwilling to give up arms without having previously settled pressing socio-economic issues broadly connected to federalism, autonomy, governance in ethnic areas, economic interests and the reintegration of their units into civil society or state apparatuses. Solutions to this impasse have long seemed far from being put on the table partly due to the fact that EAOs want to hold a share in the control over the means of violence. To this extent the peace process highlights the question of whether disarmament is a necessary pre-condition for peace in Myanmar.

A question that can be extended more broadly to armed conflicts in general and that is engrafted on broader issues such as the interrelations between arms dynamics and armed conflict (as a particular form of armed violence). A question that first requires answering to a broader one: why should we care about the issue of arms, disarmament and SSR in conflict and peace processes?

The dilemmas of disarmament and security reform in peace processes

Security Sector Reform (SSR) generally refers to the set of measures undertaken to restructure the state apparatuses providing security. The concept remains particularly blurred, varying greatly from institution to institution, area to area, due also to the fact that it revolves around controversial elements such as the notions of “security” and “state”.iiThe U.S. Department of State and Department of Defence for example define SSR as the

“set of policies, plans, programs, and activities that a government undertakes to improve the way it provides safety, security, and justice. The overall objective is to provide these services in a way that promotes an effective and legitimate public service that is transparent, accountable to civilian authority, and responsive to the needs of the public.” iii

What remains less blurred and central to the SSR concept is the idea that security should be provided as a public service by legitimate institutions in a way that is accountable, transparent, and indiscriminate. For this reason, when enacted in post-conflict contexts, SSR is considered to be an integral and essential component of peace processes in order to eventually reach stability and democracy. From this perspective, the concept of SSR seems to be connected and respond to a precise teleology whereby conflict is understood as a disruption of state and order that needs to be repaired through the achievement of stability and peace in view of the eventual restoration of, again, state and order. A state-centric teleology of conflict and sovereignty that is intrinsically permeated by a similar conception of forms of governance, with the state at the apex and different forms of political order considered as backward and incomplete.

In post-conflict contexts of course government and military institutions are not the only actors involved in the provision of security as a public service, thus the need to involve in SSR also other actors playing a role in security provision such as armed groups, paramilitary groups, or community police. Exactly because of this teleology and due to the fact that the provision of security by non-state armed actors is understood as a fallacy in state-centric perspectives of governance, disarmament of these non-state actors is conceived as a precondition for efficient and effective SSR and successful long-term peace processes. Outside a state-centric perspective though, unless legitimacy, accountability, and all the rest are ensured, it appears clear how for different kinds of political communities arms and control over means of violence can represent a form of protection and opposition vis à vis the projection of central power and authority in the provision of security as a public service and governance more broadly. Thus, a sort of dilemma of DDR-SSR seems to emerge: is disarmament per se a “good” thing? Does it lead by itself to a more accountable, transparent, legitimate and indiscriminate provision of security?

Taking the case of Myanmar armed conflicts for instance, this dilemma emerges neatly when delving into the process of demining and clearance of remnants of war in Government Controlled Areas (GCAs) and Non-Government Controlled Areas (N-GCAs).

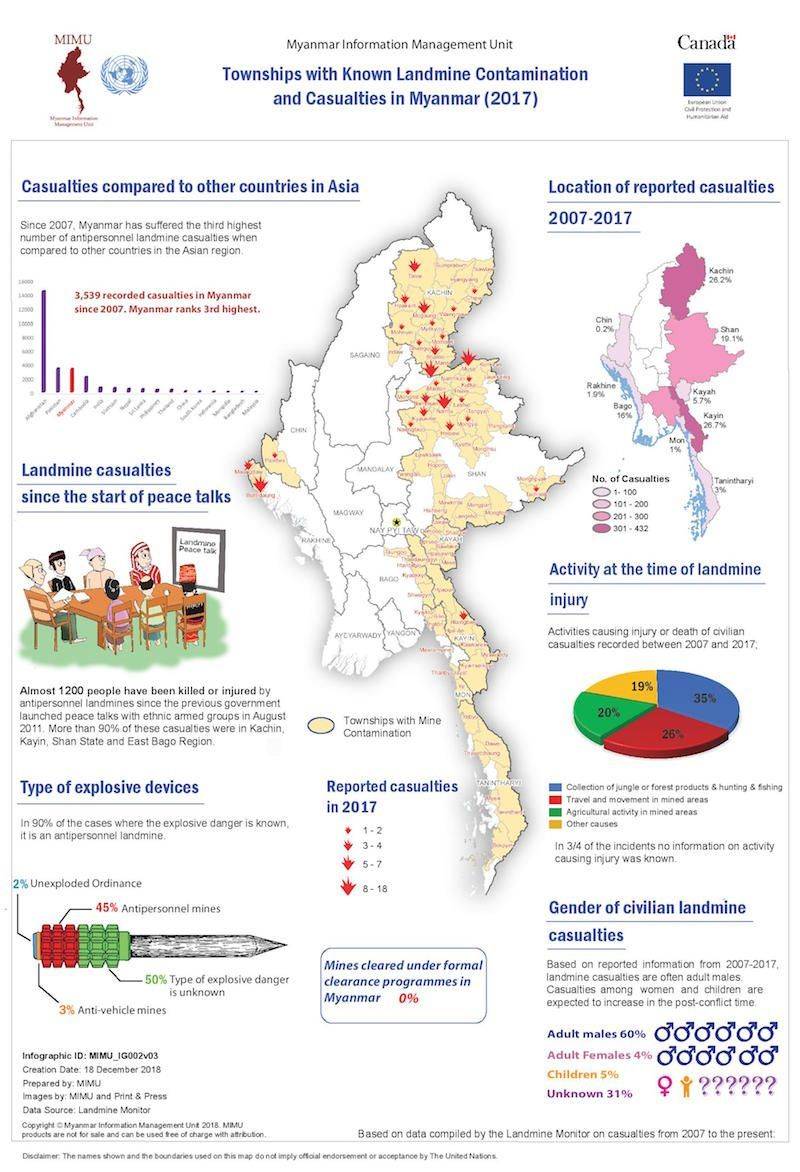

Myanmar is one of the most affected countries by landmines and other explosive remnants of war (ERW)worldwide. It ranks third in Asia for the period 2007-2017, with a total of 4,193 casualties since 1999 (537 killed; 3,538 injured; 118 unknown).

The most affected areas are: Karen/Kayin, Kayah/Karenni, Shan, and Kachin states. In these States authority and governance are hybrid and spatially differentiated. In fact, certain areas are controlled exclusively by EAOs and others by the government and the Tatmadaw, while “mixed administration” and grey areas also exist in which EAOs, the government and the Tatmadaw exercise authority fluidly.ivAcross these territories several scales of political communities exist: the head of village, the village administrator and other governmental branches, EAOs, EAOs’ political branches, village militias and paramilitary groups, or the Tatmadaw - each of which with their internal dynamics and complexities. Furthermore, authority and governance, who and how provides it, can vary greatly from place to place even in areas controlled by one or mixed actors.

At this stage no decontamination activities have started to actually remove mines and other remnants of war from the ground. The process is stalled for several reasons. The issue of demining and more broadly disarmament has not been clearly agreed upon in the ceasefires (NCA or bilateral ceasefires). Some mechanisms have been put in place to enact and monitor violations of ceasefires such as military codes of conduct that establish the removal of arms and armed actors from religious sites, schools and villages (although minor and less minor breaches of these provisions often occur) and Joint Monitoring Committees (JMC), but no delimitation of the areas that should be demined has occurred. This is due to lack of agreement upon who should delimit which areas and eventually who should remove the arms from the ground. In fact, the level of trust between the government, the Tatmadaw, EAOs and communities is rather weak, especially in some parts of the country. In turn, demining and disarmament, even in their most simple forms, are often understood as processes that would eventually remove the means of protection of last resort against the encroachment of the government and the army in areas populated by ethnic minorities, allowing them to occupy land and resources, relocate populations or build institutions in the absence of representation for minorities and transparent disputes resolution mechanisms.v

Even the simple referral of the identification of hazardous items found on the ground can be problematic. For example, if a person encounters an unexploded ordnance (UXO) or a suspicious object and wants to report it to the authorities it might not be so straightforward. In theory, following the administrative set up she/he should report to state institutions and the referral would continue up until the branches of the Tatmadaw in charge of clearance operations. At the same time though, if she/he lives in a “mixed administration” area or if the community she/he lives in has strong relations with EAOs, then proceeding through the formal process might not be the preferred solution as it might jeopardize the community and/or the EAO.vi In any case, even once the presence of this object has been reported the actual delimitation of the area and removal remain highly contentious. Removal of arms, especially of landmines, in a way entails the reconfiguration of the current security complex with potential implications for authority and governance in local areas.

Eventually it appears clear how questions of arms availability and arms control in conflict and post-conflict contexts are interrelated with the configurations of authority and governance from a socio-political and spatial perspective - meaning how authority and governance are territorialized, i.e. the practical, symbolic, and institutional construction of territory, and how they impact different scales of political communities as well as different places.vii

The linkages between arms and conflict dynamics

Yet, little is known about the relations between arms and conflict dynamics and the risk, as for other resources, is often to understand weapons in a deterministic way, looking at them as mere material/physical aspects of conflict while missing instead social processes revolving around weapons and arms control. After nearly three decades of research on arms and armed violence – specifically here I refer to the small arms and light weapons (SALW) niche of this issue – there are at least two very basic and general points that I think can be drawn to avoid this risk.

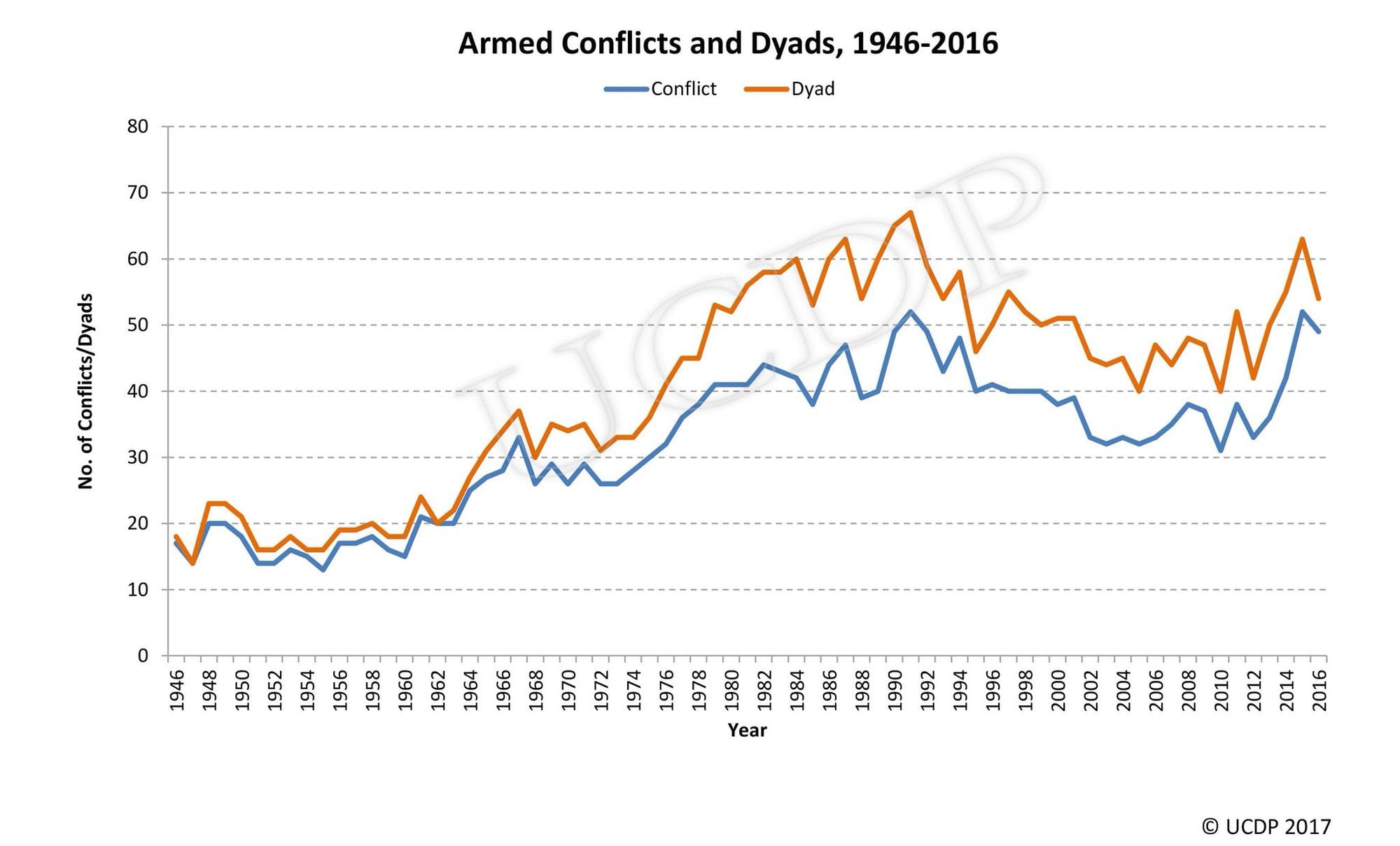

The first is connected to the proliferation of armed non-state actors and firearms in contemporary conflicts. In Myanmar for example currently there are 20 Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs), in addition to a conspicuous number of paramilitary organizations: 23 so-called Border Guard Forces (BGFs), 15 People’s Militia Forces (PMFs) and an estimated number of 5.000 local militia groups. The case of Myanmar can be considered exceptional even in relation to the general trends about the proliferation of non-state armed actors in conflict. Research by the International Committee of the Red Cross has shown that the number of internal armed conflicts has increased from 30 to 70 between 2001 and 2016. Interestingly, the number of parties to these conflicts has also grown exponentially to the extent that today only 1/3 of conflicts involves only two parties while the rest has many more. A quick glance to the UCDP-PRIO armed conflict dataset about active dyads and conflicts by year provides an immediate representation to these trends.

As it can be observed in the graph, the first considerable gap between the number of conflicts and the number of dyads1by year has to be traced back to the late 60s. Interestingly, the late 60s represented a crucial moment also for the spread of automatic firearms technology worldwide. While the development and spread of automatic weapons designs and production capacity occurred throughout the 50s and 60s (Chivers C.J.), between the mid60s and mid80s the global legal trade in firearms witnessed a particularly florid phase with the transfer of manufacturing technology, surplus firearms and new stocks to African, South American and Asian countries (Bourne M., 2007). Moreover, historically the same period is considered to be a turning point also for the flows of firearms to non-state parties in conflict areas (Bourne M., 2007).

The parallel between the proliferation of non-state armed actors and the availability of automatic firearms, raises the question of how weapons availability and control dynamics interrelate with the dynamics and trajectories of non-state armed actors. Nonetheless, to avoid deterministic approaches to these linkages, it is important to conceive the availability of arms to non-state actors in terms of access to and control over arms (Marsh 2007).

The second point is related to the interactions between firearms availability and violence dynamics, and offers a specification to the first point. Research on violent deaths has been rather divided on the issue of firearms availability as no clear correlation has been found between the latter and killings in general. Yet different findings seem to point to another direction suggesting some connections between the availability of small arms and violence. Illustratively, one might turn the attention towards a specific form of violence: mass shootings. Research from 2016 analyzed the global distribution of mass shooters from 1966 to 2012 in 171 countries and found it attributable to cross-national differences in firearms availability. In other words, countries such as the US, Yemen, Switzerland, Finland, and Serbia which were top 5 countries in firearms civilian ownership rates in 2007 (top 16 in 2017 per capita: Karp, 2018) were also top 15 public mass shooters countries per capita. Yet, countries such as Switzerland and Finland are by other indicators usually considered particularly safe and register low levels of violence notwithstanding the high quantity of firearms in the civilian population.

This discrepancy suggests that, when analyzing the dynamics of violence through the prism of arms, it is not a mere question of number of weapons present in a given location, but it is especially relevant to consider how the issue of access to arms and arms acquisition is controlled and regulated. Far from feeding into National Rifle Association (NRA)-type of statements – such as ‘it is not the gun that triggers violence but the finger behind it’ – going back to the question of arms and conflict dynamics this entails the need to focus on actors and their social and political actions in relation to arms and arms control in conflict and post-conflict situations.

Reading these two points from the perspective of the peace process in Myanmar, it helps to understand that the issue of DDR-SSR – in other words, how the means of violence will be regulated – is indeed deeply connected to the future configurations of authority and governance with all the implications in terms of land, resources and more in general authority and governance that this might entail. In other words, while the acquisition of arms by non-state actors impacted on the constitution and entrenchment of hybrid governance and overlapping forms of sovereignty, arms control by state and non-state actors should inform the peace process. Actual disarmament of non-state armed groups will be extremely contentious and difficult if it is not preceded by forms of reintegration of combatants and agreements about how to deal with questions of legitimacy, autonomy and representation of minority people. While pursuing the NCA and related interim arrangements might seem a sensible way forward, it should be taken into account that the agreement has various flaws that pose serious obstacles towards both the DDR/SSR process and the question of federalism.

Notes

1 “A conflict dyad is two conflicting primary parties of which at least one is the government of a state. In interstate conflicts, both primary parties are state governments. In intrastate conflict dyads the nongovernmental primary party is an organized opposition organization.” (Pettersson and Eck, 2018, p. 536)

i The Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement between the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar and the Ethnic Armed Organizations, 2015, Chapter 3, Art. 6.

ii For an extended literature review see Gindarsah, I. 2015, Security Sector Reform: A Literature Review, Peace Capacities Network, Norwegian Institute of International Affairs: Oslo.

iii U.S. Agency for International Development, U.S. Department of Defense & U.S. Department Of State 2009, Security sector Reform.

iv Author’s interview with NGO worker based in Loikaw, Kayah/Karenni State, Yangon 22 February 2019.

v Author’s interview with humanitarian mine action expert, Yangon, 21 February 2019.

vi Author’s interview with NGO worker based in Loikaw, Kayah/Karenni State, Yangon 22 February 2019.

vii Korf, B., Raeymaekers, T., Schetter, C. and Watts, M.J. 2018, Geographies of Limited Statehood, in: Draude, E. Börzel, T.A. and Risse, T. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Governance and Limited Statehood, Oxford University Press: Oxford, pp. 167-188.

References

Chivers, C.J. (2010), The Gun, New York: Simon & Schuster.

Bourne, M. (2007), Arming Conflict. The Proliferation of Small Arms, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Marsh, N. (2007), Conflict Specific Capital: The Role of Weapons Acquisition in Civil War, International Studies Perspectives 8, 54-72

Karp, A. (2018), Estimating Global Civilian Held Firearms Numbers, Geneva: Small Arms Survey.

For an outstanding photographic documentation about Myanmar's forgotten wars and mining industry see Hkun Lat's and Hkun Li's websites.

Acknowledgements

Cover photo: Tunnel of contrast in Old Bagan, by C Chapman, 2017, on Unsplash.