The brutal attacks by Hamas on 7 October and the genocidal slaughter in Gaza that followed have reignited a reflection on violence and its use in liberation struggles and in contexts where it arises in conditions of injustice, inequality, siege, and dispossession. Where do we stand in the critical debate on 'violence'? Can this debate inform the lens through which we take position on Israel and Palestine? Can this debate remain grounded in history and emancipatory goals, while not abandoning ethical and practical positions that explore non-violence?

In the aftermath of 7 October, many cases of collective and individual mobilisation in support of a ceasefire and an end to the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories have been met with police repression, censorship and misrepresentation of content, meaning, or intent. The debate has been polarised, and calls for non-violent transnational solidarity practices sensitive to conditions of injustice, dispossession, and siege have been systematically accused of anti-Semitism and delegitimised. This was just one of many signs that the violence perpetrated by Hamas is largely used to undermine the Palestinian cause as a whole.

However, the use of violence and non-violence are rarely mutually exclusive in resistance and liberation struggles. Historically, these struggles have tended towards more or less violent strategies - in relational processes - without being mutually exclusive in absolute terms. Acknowledging this would predispose us not to lose sight of the often invisible forms of Palestinian non-violent resistance, in its collective but also intimate manifestations, and to recover an argument in favour of non-violence. I will try to navigate these troubled waters by bringing together theoretical arguments and situated experiences for non-violent emancipatory resistance and transnational solidarity practices for Palestine and beyond.

From abstract peace to concrete non-violent resistance

Drawing fruitfully on, among others, Frantz Fanon and Mahatma Gandhi for the analysis of contemporary world politics, philosophers and thinkers such as Judith Butler, Etienne Balibar and Leela Gandhi have recently engaged vividly with issues of (non)violence, which have dramatically come back to the fore in the aftermath of 7 October. They all come to conclusions in favour of non-violence and practices of non-violent solidarity (or, more specifically in Balibar’s case, the politics of anti-violence, Balibar 2016) that is grounded in a reflection on violence itself, in its causes, determinants, and consequences. For them, the idea that politics can be immune to violence and social conflict is an abstract, ahistorical, and morally absolute vision. This argument is based not only on ethics but also on concrete historical experiences. Non-violent practices and campaigns of civil disobedience around the world have usually been interspersed with many other forms of resistance, sometimes violent. In the glaring case of India, for example, Gandhian ahimsa and satyagraha and the political project derived from them did not alone lead to the liberation of India, though they were crucial. The armed resistance groups of the Indian peasantry made a major contribution to the independence struggle.

If, on the one hand, it is not possible to eliminate clashes, political frictions, and social conflicts, on the other hand, politics can commit itself to transforming them to avoid destructive and cruel drifts. Violence is a relational process that can have different ontological manifestations. It is not an immanent, static condition, but a «mobile and metamorphic contradiction», a process along a continuum in which it can be intensified or attenuated. Violence is performative, and there is a condition of immanence of its ends to its means (that is, it is not always possible to separate violence as a means from the violence that becomes an end). It is therefore not possible to assume that we have control over this metamorphic process of physical violence, as if we were using a joystick. As Gandhi believed, but also as the psychiatrist Fanon was also able to experience in his clinical studies in post-colonial contexts (although for him violence could have a political and strategic validity in resistance and liberation struggles[1]), violence produces a transformation to the ends for which it is applied, and conditions or «creates in its image» (Fanon 1968) the subjects who carry it out. Violence essentially produces scars and effects that are difficult to control. It can reach to extremes: 'barbarism' as Balibar puts it, or to «total destructiveness» to use Butler’s terminology (Butler 2020).

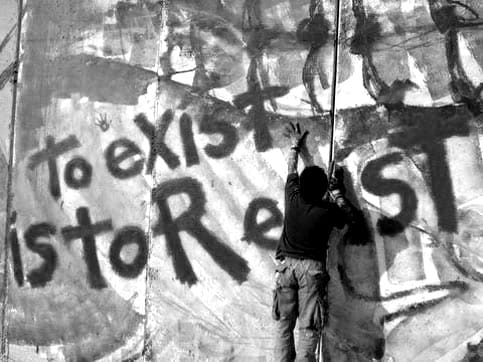

The potential of anti-violent politics therefore lies in activating forms of civility, forms of containment of violence in its extreme instantiations, including while violence unfolds. In practical terms, non-violent (or anti-violence) political strategies are those that use of “bodies and souls” (see Gandhi 2008) and that create connections, physical and symbolic, between them. They are those demonstrations that nullify and overturn the potential of extreme violence of annihilation, and that make people say: “We are still here to resist”. They are solidarity boycotts, street movements, and individual actions that make use of bodily and creative gestures. These gestures and actions create a connection between emancipation (in the immediate sense of presence that cancels annihilation) and non-violence, therefore making the latter more concrete and not an abstract concept. Justice and peace do not come about spontaneously, but only when the powers and interests at the root of violence are confronted in their concrete unfolding. A non-violent practice is therefore a practice that offers the possibility of transforming violence - at the very moment it takes place - into non-violent emancipation. Following this, even under extreme conditions, where structural asymmetries and total violence asphyxiate any form of peaceful resistance (as in the case of Palestine and Gaza), non-violent politics and practices still have their potential to transform violence in an emancipatory sense. The potential and its non-violent expressions of resistance have made the history of Palestine, we should only stop silencing or making it invisible.

The veil of silence over Palestinian non-violent resistance

In the case of Israel and Palestine, non-violent expressions of resistance (civil disobedience, the building of barricades and roadblocks, boycotting or non-cooperating with administrative or military officials, labour strikes etc.) dominated at least until the end of the First Intifada and never disappeared even in Gaza governed by Hamas. Recent powerful testimonies of non-violent mobilizations include the Bab Al-Asbat sit-ins in East Jerusalem in July 2017, in which Palestinians used their physicality and bodies to concretely challenge security and high-tech devices and infrastructures in East Jerusalem, or the series of protests between 2018 and 2019 known as the “Great March of Return”, in which thousands of Palestinians participated together, this time at the Gaza border. Despite their largely peaceful nature, these episodes of large-scale street participation were also the most brutally repressed. Moreover, they rarely captured the world’s attention in the way that acts of violence did. Palestinian pockets of resistance (including but not limited to Hamas, which was officially born in 1987) to achieve freedom even by violent means increased as these peaceful expressions of non-violent resistance were met with harsh repression. They then increased as the continuum of violence moved towards total violence.

Intimate forms of Palestinian non-violent resistance have often been associated with the concept of ṣumūd (صمود), which expresses an ethical as well as a practical and embodied stance[2]. Raja Shehadeh, a Palestinian writer and intellectual, has conceptualized ṣumūd as a non-violent stance that represents a middle ground between passive acceptance of the occupation (and thus collusion with it) and violent struggle. ṣumūd is thus a political strategy for holding on to the land in everyday life under occupation and siege, and it has inspired many active forms of mystical or bodily disobedience and resistance, including artistic and creative ones. Resistance through the use of the body, the meaning of the land and the return to the land, are therefore non-violent, principled practices that have always informed Palestinian resistance. Making them invisible distorts the complexity of the Palestinian resistance and reduces it to Hamas’ violent strategies.

After 7 October

If the total violence of the occupier has stifled the efforts of non-violent resistance, the use of violence, even when it takes the form of armed resistance and even when it resorts to terrorist methods, is always the result of a political project and a strategic choice among a repertoire of possible choices. In this sense, on 7 October, Hamas acted on its own behalf and according to its own political project, for which it is responsible. The point, however, is to understand how the choice of violent action prevailed over others within a particular faction or within the Islamic movement as a whole, or how the capacity to carry out the attacks was created. Although it is perhaps too early to examine these aspects, the attacks represented a breakthrough, not least because they were a litmus test of the extreme levels reached by the spiral of violence. Hamas has always operated in fertile ground for non-violent discourses and practices inspired by historical liberation struggles. If until now Hamas seemed to be trying to gain a foothold in this terrain[3], 7 October marked a radical processual turn: the continuous suffocation of non-violence (and its international mediatic isolation) and the transactional deals for a status quo between Hamas and Israel (i.e. by allowing Qatari funds in exchange for Hamas guaranteeing stability in Gaza) have raised the bar of the politics of death against the Palestinian people to an extreme level. This turn has dramatically exposed the trivial and wreckful effects of strategies and political projects that aim to respond to the violent occupying state with the same violent means.

Acting the politics of non-violence as the violence of the oppressor unfolds seems a more promising way to channel concrete efforts of solidarity, mobilisation and resistance, and a very urgent goal. Granted that Palestinians have a right to determine their own future, from a transnational solidarity standpoint these politics could be translated into mobilising for an immediate ceasefire, the dismantling of the military-industrial war machine, the liberation of the occupied Palestinian territories, and the end of the apartheid state. Whatever position one takes for or against the use of violence in liberation struggles, including in the context of Israel and Palestine, it is important to do so in the light of a debate informed by situated ethical and practical experience and to avoid invisibilizing existing non-violent experiences.

References and insights

Balibar, E. (2016). Violence and Civility. On the limits of political philosophy. Columbia University Press, New York.

Balibar, E. (2020). From Violence as Anti-Politics to Politics as Anti-Violence. Critical Times, 1 December 2020; 3 (3): 384–399. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/26410478-8662288

Butler, J. (2020). The Force of Nonviolence: An Ethico-Political Bind. Verso, London.

Fanon, F. (1968). The Wretched of the Earth. Grove Press, New York.

Gandhi, L. (2008). SPIRITS OF NON-VIOLENCE. Interventions, 10(2): 158–172. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13698010802145077

Mason, V. & Falk, R. (2016). Assessing Nonviolence in the Palestinian Rights Struggle. State Crime Journal, 5(1): 163–186. https://doi.org/10.13169/statecrime.5.1.0163

Obaid, H. (2018). Protests and the Return of Hamas’s Political Fortunes. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/76792

Pace, M., Shehada, M., & Abu Mustafa, Z. (2021). Interpolating Gazans’ non-violence: Responsibilities in the academy and the media. Partecipazione e Conflitto, 14(2), 584-603. http://siba-ese.unisalento.it/index.php/paco/article/view/24248/20222

Shehaded, R. (1982). The Third Way: A Journal of Life in the West Bank (Quartet Books, London). But also more recently: Occupation Diaries (OR Books, New York).

[1] Fanon is often mistakenly considered an apologist for violence. It is true that for Fanon the total violence of the colonial system could only be compared (and eliminated) with the armed struggle of the colonized, but he does not make an aesthetic exaltation of violence, if anything he identifies its political potential for the colonized but also the profound traumas that it leaves.

[2] The Arabic word ṣumūd means literally ‘steadfastness’. Those who exhibit ṣumūd are referred to as ṣamidin. As a concept, it refers to both an ideological and cultural stance and to a political strategy that emerged in the wake of the 1967 Six-Day War and inspired Palestinian resistance.

[3] It is useful here to refer to when, in April 2018, during the “Great March of Return protests”, top Hamas leader Ismael Haniya gave a speech with iconic portraits and quotes of Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela, and Mahatma Gandhi in the background.