In the last few days, several media have accounted in detail for the Sheikh Jarrah events (the risk of forced eviction of several Palestinian Jerusalemites from their homes), which have been one of the triggers for the clashes currently shaking Jerusalem and the whole country. Less attention has been paid to the spatial context in which these events unfold. However, in order to fully understand the Sheikh Jarrah’s case, one needs to be aware of how, since 1967, Jerusalem has been physically transfigured by a systematic series of urban policies and projects aimed at materializing the Israeli domination of the entire city. Otherwise, one runs the risk of not distinguishing the ‘wood from the trees’. To this end, I provide here a concise and simplified guide, by points, to the ‘spatial context’ of Sheikh Jarrah’s case.

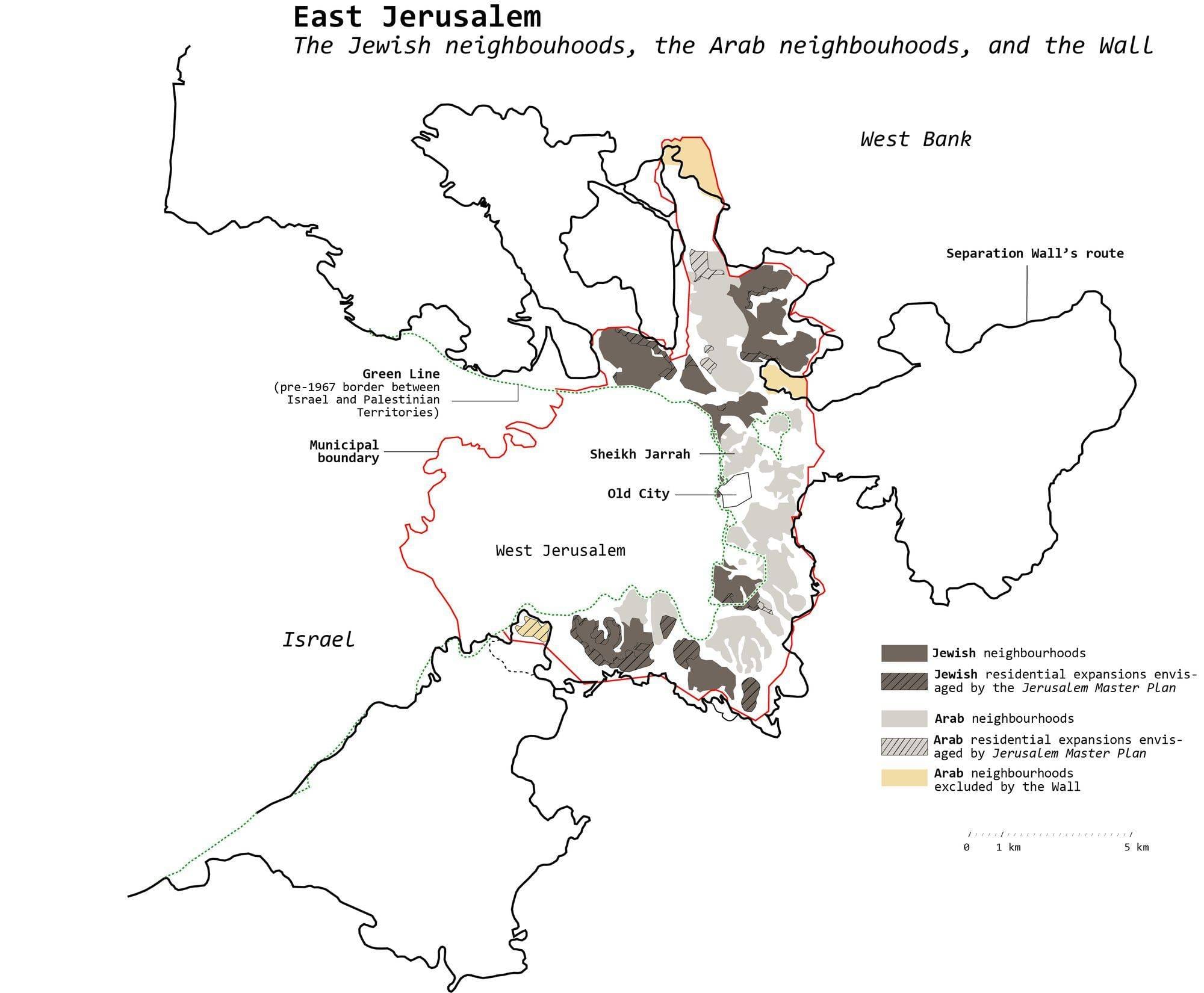

1. At the end of the 1948-49 Arab-Israeli war, Jerusalem was divided into two main parts: West Jerusalem, under Israeli control, and East Jerusalem, under Jordanian control. This is the spatial configuration of the city still recognised as legitimate by the majority of the international community.

2. In 1967, Israel militarily occupied East Jerusalem (among other territories) and subsequently declared the ‘united and complete’ city as the indivisible capital of the State of Israel. The United Nations have never recognised this annexation and have repeatedly called for a return to the pre-1967 borders.

3. After the Six-Day War, the battle for Jerusalem did not end; rather, it changed face. To use the words of David Ben-Gurion, the first Prime Minister of Israel, the goal of this new phase of the battle was to make the city physically “an organic and inseparable part of the State of Israel, as it is an inseparable part of the history and religion of Israel and of the soul of our people”. To this end, Israel implemented resolutely a series of action to prevent any possible attempts to divide the city (or to remove some part of it from Israeli control), by creating facts on the ground whose elimination would be problematic, if not actually impossible. These actions materialized in a twofold process that the Israeli geographer Oren Yiftachel defined as the simultaneous Judaisation and de-Arabisation of the city.

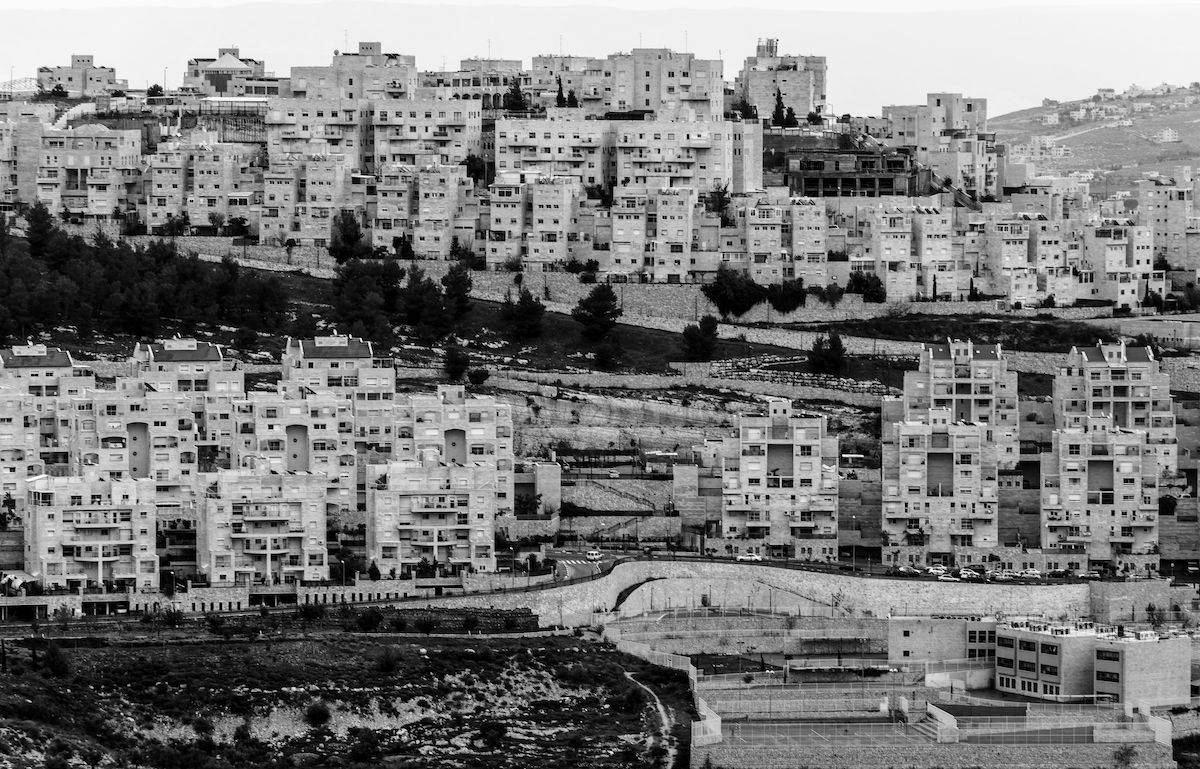

4. The process of Judaization took place mainly through the physical expansion of the Jewish city into the Palestinian areas of East Jerusalem. In particular, a massive residential building operation was promoted which, within a few decades, paved the way to the settlement of more than 200,000 Jews (about 40% of the Jewish population of the entire city) in East Jerusalem*. As Moshe Amirav, an Israeli political scientist, stated, “from an urban perspective, the Jewish neighborhoods that were to be built on these lands were completely unnecessary – […] Jews could build on lands that were abundantly available in the west of the city. [Public authorities] openly admitted as much, acknowledging that the purpose of the appropriations was to establish control in Arab territory, and not an answer to a housing shortage”. It is worth noting that most of these Jewish residential areas were built with the support of public authorities, benefiting only the Jewish population at the expense of the Palestinian Arab population: “Over a third of the land [in East Jerusalem] […] was expropriated from its Palestinian owners for the establishment and expansion of the Jewish neighbourhoods, under the pretext of catering for “public needs”. The use of the term “public” reveals more than anything else the government’s political bias: the “public” on whom expropriations were imposed always comprised Palestinians; the “public” who enjoyed the fruits of the expropriation always exclusively comprised Jews” (Eyal Weizman, Israeli architect). The (mild) international condemnations of this process have had no concrete effect in stopping or curbing the Judaization of the city.

5. The process of Judaization has been coupled with a relentless process of de-Arabisation, aimed primarily at diminishing Palestinian control of East Jerusalem’s land. This has mainly been translated into almost insurmountable obstacles to the urban expansion of Arab neighbourhoods – these obstacles have mainly taken the technical form of urban planning and building measures and regulations. The de-Arabisation of Jerusalem has also been pursued through the expulsion of Palestinians from areas they have long inhabited, as in the case of Sheikh Jarrah. The latter cases are a striking and dramatic, but admittedly quantitatively minor, part of the de-Arabisation process, whose ordinary forms are far more subtle. These include, for example, the failure to provide Arab neighbourhoods with the most basic public services, which has made the daily life of Palestinian Jerusalemites extremely difficult. The words of Teddy Kollek, mayor of Jerusalem for 28 years, leave no room for misunderstanding: “We said over and over that we would equalize the rights of the Arabs to the rights of the Jews in the city – empty talk... They were and remain second and third-class citizens. For Jewish Jerusalem I did something in the past twenty-five years. For East Jerusalem? Nothing! What did I do? Nothing. Sidewalks? Nothing. Cultural institutions? Not one. Yes, we installed a sewerage system for them and improved the water supply. Do you know why? Do you think it was for their good, for their welfare? Forget it! There were some cases of cholera there, and the Jews were afraid that they would catch it, so we installed sewerage and a water system against cholera”.

5. The final step in this battle for the material appropriation of East Jerusalem, is the construction of the Separation Wall, which solidifies the external borders of the “unified and indivisible Greater Jewish Jerusalem”, while at the same time operating selective political inclusions and exclusions. On the one hand, it includes several Jewish settlements in the West Bank, located in the surroundings of Jerusalem. On the other hand, the Wall amputates some Palestinian areas in East Jerusalem that, even if they lie within the city borders, have been left on the Palestinian side of the barrier – with all the dramatic consequences in terms of daily life that this means for the tens of thousands of Palestinian Jerusalemites living here.

It is against the backdrop of this slow but inexorable spatial conquest of the city by Israel that the recent events of Sheikh Jarrah must be read. They are just one dramatically striking moment in the silent war of cement and stone that began in 1967 and which, despite international silence, has never stopped. From a spatial viewpoint, Israel has almost won this war: by physically occupying the eastern part of the city with Jewish buildings, infrastructures, services and industries, Israeli authorities have secured their control over the entire city. Today, the Jewish city extends on both sides of the Green Line [that is, the pre-1967 border between Israel and the Palestinian Territories], with only a few interruptions constituted by Arab areas. In the eyes of tourists and occasional visitors strolling through the city, Jerusalem can already be perceived as an Israeli city, because no marked differences exist between West and East, apart from the “accident” of some Arab neighbourhoods – which appear to be anomalies, poor and degraded enclaves alien to the rest of the Israeli urban space. Sheikh Jarrah’s uprising, unfortunately, will not be able to change this situation. But it will help make clear, once again, the brutality and illegitimacy of fifty years of Israeli urban policies – in the face of which one can only be equidistant through ignorance or bad faith.

For an in-depth analysis of these issues, see Francesco Chiodelli, 2017, Shaping Jerusalem. Spatial planning, politics and the conflict. Routledge, London and New York).

* Note of the editor: with over 330,000 residents in 2016, Arabs make up around 40% of the Jerusalem population. This includes the approximately 140,000 inhabitants of the areas north and east of the Separation Wall that lie within the municipal boundary (Kafr ‘Aqab and Shu’fat Refugee Camp, shaded in light orange on the map). An upcoming companion piece by the same author will analyse in detail the demographics of Jerusalem. Stay tuned.

Cover photo by Davide Locatelli (C) 2016, the Jewish neighbourhood of Har Homa, in East Jerusalem.