The EU does not see itself as a stranger to the Arctic and claims multiple links to the region, whether on a geographical, legal, economic, environmental, research or regional development-related level. This blogpost analyzes how the EU depicts itself as a “geopolitical actor” in the area, starting with the development of policies towards the Arctic region, expanding on but also differentiating from the Northern Dimension (ND) and the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP). It focuses mainly on the latest “Joint Communication (of European institutions)” of 2021 through the lenses of critical geopolitics, and it aims at “deconstructing” the EU’s image and the narrative used to legitimize its role in the “region”.

Introduction to the European Arctic Policy

The EU clearly differs from a prototypical state actor because of its sui generis polity, identity, history, and lack of common military and foreign policy power.

The concretization of an alleged EU’s geopolitical “agency” focuses on regional-scale policies (among the most prominent: Black Sea Synergy, EU Arctic Policy, European Neighbourhood Policy, Northern Dimension, Sahel Security-Development Strategy, etc.). It relies on the fundamental intake of a double process of a self-perception of stability as opposed to external factors depicted as a threat, such as civil wars, mass migration, terrorism, climate change, or the rise of China and Russia. The perception of such an outside is arguably linked to the creation of a European domestic “cosmos”, that is the socially constructed “space” in which EU-proper structures, processes, and flows feed mechanisms of power legitimation and identity affirmation (Bachmann 2015).

Embedding such conceptual framework with historical contextualization, one needs first to clarify why a proper Arctic policy was developed later (2008) compared to the Southern and the Eastern partnerships (ENP2004) or the upgrade of ND institutions (2006), which involved the Arctic partners Russia, Iceland, and Norway. I suggest that the creation of EU policies towards the Arctic and their underpinning geopolitical imaginary, like in any other geopolitical “projection”, preliminarily required the EU’s ability to present itself as a unified political actor, thereby overcoming the patchwork of various institutional interests and diverging voices that sometimes characterizes EU policymaking. A political rationale and its related imaginary were therefore needed to prioritize EU action over “individual” Member States’ particular interests. In this case, the development of a “unified” Arctic program traces its origins mainly to the rising climate change awareness of 2007-2008, the central junction in the logic of its new narrative, and can be seen both as an extension of and at the same time a distinct project from the ND, overcoming the “cooperational” approach of the latter. While earlier it was confined to a marginal note in EU policy, the Arctic progressively appeared on the EU’s “neighbourhood radar” since the region’s critical changing geostrategic dynamics were supposed to have consequences for the EU’s security and interests.

A gradual recognition of EU’s multiple links to the region (in terms of climate, energy, resources, security), combined with the expectation that interdependence would significantly tighten over the next decades, prompted EU institutions to develop an EU Arctic policy toolkit and to progress further into setting common positions (Raspotnik & Østhagen 2021). By 2019, the EU had eventually published ten Arctic policy documents: three Joint Communications by the Commission and the HR/VP in 2008, 2012 and 2016; three related Conclusions by the Council in 2009, 2014 and 2016; and four Resolutions by the European Parliament in 2008, 2011, 2014 and 2017.

“Deconstructing” the EU’s Arctic geopolitical imaginary through the video presenting the 2021 Arctic policy update

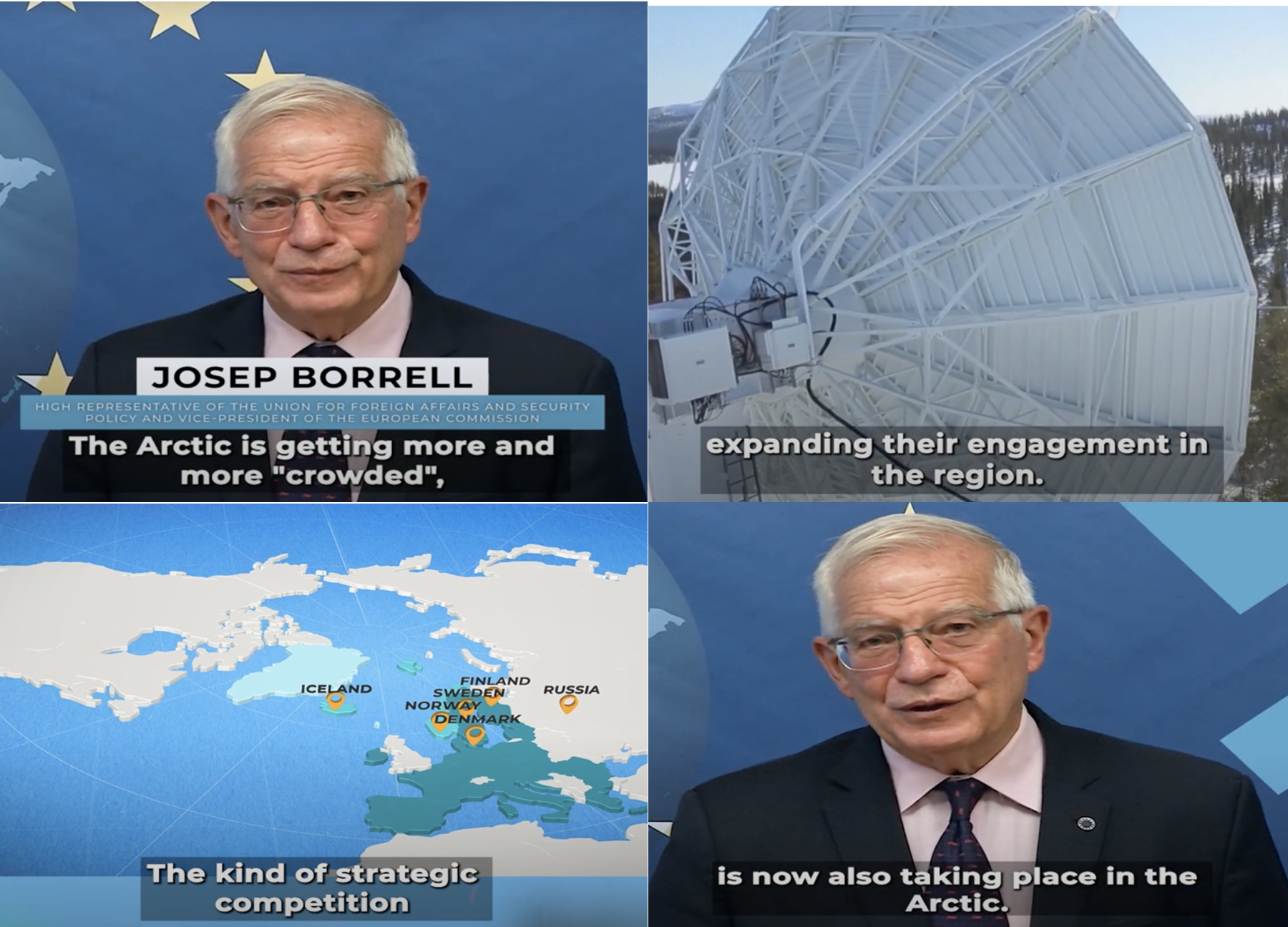

This section explores the geopolitical imaginary conveyed in the 2021 Joint Communication, by looking in particular at the video issued to accompany its release. The frames that will be presented arguably aim at stressing both EU’s self-identification and the dialectics between internal stability and external turmoil (Browning 2018).

Interestingly the video does not appear to focus on the Arctic itself, however it could be defined, but on the EU and its agency in the region. The opening frame suggests that what ultimately matters for the EU is being perceived from the outside as a unitary and cohesive actor: from this perspective, the EU’s own speech “performs” the Union, and aggregates a heterogeneity of institutions, member states, and their respective positions into a unique Arctic policy. Despite its quite recent interest, the EU is presented as an already “major player” in the region, with a subsequent unitary “engagement” that is “expanding”.

The region is depicted as a “global Arctic” (Heininen & Finger 2018), which consists of the primary condition allowing the EU to have a geopolitical agency in the first place. The “global Arctic” definition challenges interpretations of the Arctic as a regionally enclosed territory exposed to and depending on geographically neighbouring state actors. It rather stresses the fundamental entanglement of the region with complex and interdependent ecological, economic, environmental and cultural processes that can be faced only on a global scale, therefore legitimizing the EU’s agency and interests.

Legally, the region’s governance is shaped by a complex array of international treaties and programs, bilateral agreements, national and subnational laws, and governmental and non-governmental initiatives. Politically, the Arctic Council (AC) is the main institutional structure, composed of eight member states (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States, which all neighbour the region), six indigenous people’s organizations as permanent participants, and a vast group of observers including thirteen non-Arctic states, fourteen intergovernmental and inter-parliamentary organizations and twelve non-governmental organizations. At first glance, this institutional set-up of the region, with states prevailing and non-state actors in second place, helps promote a certain imaginary about the Arctic and effectively contributes to defining a spatial order of the region premised on statehood and proximity. Such “ordering” results in the consolidation of a “territorially bounded future vision of the Arctic” where the possession of an Arctic shoreline underpins the Arctic’s membership perception of who is eventually “in” or “out” (Dodds 2013). For example, such a reading is apparent if we consider the military perspective, where the region, rather than a unitary entity, is viewed as an unstable aggregate of competing national interests (with Russia being the major concern of NATO members) (Østhagen et al. 2018). It is also apparent in Canada’s domestically motivated demand for absolute control of what Ottawa views as its “domestic” waters, which hampers pan-Arctic inter-governmental collaboration (Knecht & Keil 2013).

A major debate about reforming the AC and a new approach to the organization is currently taking place since climate change-induced variations in the physical-geographical connotation of the region have triggered the interests of other actors. This stance, in turn, relies on certain political representations of the region and its subsequent governance: for local indigenous groups and permanent (state) participants, any enhanced role for observers is unwelcome because extra-territorial involvement conveys a radically different imaginary of what and whose the Arctic is (Dodds 2013).

What was once only considered as a natural icy fortification, and therefore a static geographic region, eventually came to be seen as a “multi-faceted global security risk” (Dittmer et al. 2011), politically connotated. The geopolitical representation of the Arctic as a space of “flux” appears suitable in order to understand the impetus behind EU agency. The “flux” framing coagulates in a single image a decades-long process in which the Union foresees a growing “strategic competition”. Such a representation of the Arctic spatiality helps to understand the EU’s prospective agency in it. Precisely because of its changing geography, the growing political space for “outsiders” is allowing the region to get progressively “more and more crowded”, and it is the EU mission, as portrayed in the video, to rationally “order” it.

Contrary to this narrative the other (non-EU) states in the Arctic’s shorelines tend to emphasize their own Arctic-ness, or, put otherwise, that the Arctic (region) is their own and non-Arctic actors should not interfere. For some of these countries, their Arctic territories hold a prominent place in both domestic and foreign policies, shaping their perceptions of the national self and the global outside. This narrative is now being challenged by the opening definition of the Arctic as a space of flux, in which the interests and interferences of non-Arctic state- and non-state actors, including the EU, are growing (Østhagen et al. 2018).

As part of its approach to the Arctic, the EU strategy’s development over the years illustrates the EU’s own ideational character’s projection, not only stressing the bloc’s economic weight but also its strengths as the frontrunner in regional integration, transnational governance, environmental protection and research.

EU policies (and interests) in the region are arguably premised on what one could qualify as an imaginary of the Arctic as a “soon-to-be-ungoverned” space, a “flux” region requiring new political governance. Yet the Arctic region is neither “empty” nor ungoverned: the problems the AC is unable to “govern” according to the EU depend less on a lack of institutional capacity than on the growing salience of a new “global Arctic” narrative, depicting the region as a crossroads of global challenges. In addition, the EU’s own self-perception as a harbinger of universal values safety, as opposed to other actors’ particularistic interests, was not necessarily well-perceived by some of the region’s dominant players, whose “our Arctic only” imaginary hinges on a positive understanding of their own sovereign prerogatives (Østhagen 2017).

This is noteworthy because, unlike its experience in the Southern neighbourhood, in the Arctic the EU is bound by a distinct “regional system” based on the national interests of strong state actors, in which the traditional instruments of intergovernmental relations prevail. In this context, the EU is not in a position to simply diffuse its own internal “acquis” from an agential centre to a “periphery” largely posited as passive (Kobza 2015).

Conclusion

The EU’s proposal to enhance Arctic governance reveals a latent ambivalence. Although the EU acknowledges the region’s existing governance regimes and the related rights and duties of the Arctic states, it simultaneously questions their effectiveness, arguing that only a EUropean booster might ensure that the region “remains a stable, safe, peaceful and prosperous place” (Raspotnik & Østhagen 2021).

The spatial aspects characterizing the EU’s quest for the north have been trapped in the incongruity between two distinct imaginaries: the geographically-bounded Arctic versus the EU as a global actor engaging issues it can lay a claim on from a normative/moral point of view. This tension is also evident in the geographical definition of the EU’s space of action in the region, in which the EU is stuck between a (maritime) circumpolar and a (terrestrial) European Arctic, recalling a Schmittian dichotomy between universal and spatially-grounded political and normative impetus.

Overall, it can be observed that the EU’s attempt to impose its frames on the Arctic region has not achieved tangible results. This is because traditional state actors are still capable of transforming their spatial rootedness into concrete institutional weight, which manages to counter the EU’s spatial and strategic ambitions. Undoubtedly the “space of flux” imaginary could help enhance the EU’s agency and legitimacy. Yet, in light of the existing institutional functioning, this remains largely a representation, comprehensible in a long-term geopolitical projection, but effortlessly deconstructible and hardly implementable in the short term.