The Arctic is among the world's most climate-fragile regions, being very responsive to temperature increases. In the Anthropocene epoch, the Arctic’s “surface air temperatures have warmed at approximately twice the global rate”[1]. The ocean has lost a significant part of its permafrost due to global warming. While these environmental changes are often perceived as a global catastrophe, the melting of the Arctic ice cap is not unanimously regarded as in need to be countered; “for the five Arctic nations — the US, Canada, Denmark, Norway, and Russia — it also presents an opportunity: access to promising new trade routes and untapped fossil fuel resources”[2]. This has led to a growing interest vis-à-vis the Arctic on the political arena. In particular, discussions on borders have become central since northernmost territorial delimitations are not clearly defined. Moreover, such growing interest has also been accompanied by a stronger military presence in the Arctic, promoting a fear of competition for resources in the far north.

Acknowledging this situation, the Anthropocene could be considered as contributing to a de-peripheralization of the Arctic in the political discourse, with de-peripheralization implying a “cartographic shift in perception, redrawing center/periphery relations”[3]. In other words, it constitutes a change in the conception related to a geographical area, extracting it from the peripheral position to which it had previously been relegated. This mutation occurs in conjunction with the Anthropocene, understood as “an unofficial unit of geologic time used to describe the most recent period in Earth’s history when human activity started to have a significant impact on the planet’s climate and ecosystems.”[4]

The argument of an Anthropocene-led de-peripheralization of the Arctic holds that, due to human-induced climate change, the perceptions concerning the Arctic are shifting and that the Arctic, formerly less central in political debates, is nowadays tickling the interest of the Arctic powers:

“The growing alarm over the impact of climate change upon the Arctic [demonstrates] that a region which for all of the Twentieth Century was pushed to the side when it came to the regulation of international affairs has the potential to take center stage as state interests are awoken and global concerns advance.”[5]

The increased interest in this region is firstly linked to economic concerns: the melting of the ice cap allegedly renders the Arctic an “ocean of opportunities”[6], given the natural resources present underneath. Secondly, as the Arctic becomes more accessible and exploitable, discussions on northernmost borders are emerging in political discourses, where a race or resource conflict could arise.

An ocean of opportunities

Many scholars and civil servants associate the recent increased interest in the Arctic (and thus its de-peripheralization in international discourses) with the enhanced economic potential that climate change is uncovering in the region, particularly for the Arctic nations, but not only. In fact, international gluttony toward new Arctic routes and the effortless exploitation of its natural resources has global implications. For instance, China defines itself as a “Near-Arctic State”[7] and is manifesting its interest in the opening up of a so-called “Polar Silk Road”[8] It is thus the Anthropocene and climate change that scholars identify as the impulse behind the “very recent start of Chinese Arctic diplomacy”[9]. Similarly, regarding energy resources, “the Arctic is expected to hold about 22 percent of the world’s undiscovered conventional oil and natural gas resources.”[10]. States, therefore, show a growing interest vis-à-vis the North Pole, as “the Arctic accounts for nearly 20 percent of Russia’s GDP, 22 percent of its exports, and more than 10 percent of all investment in Russia”[11] and with the melting of the ice cap its importance for the Russian Federation is likely to grow further. Similarly, the US-elected president Donald Trump was vocal in signifying its interest in Greenland, in particular given the island’s “mineral wealth”[12], which would allow the US to counter-balance China’s leading position in the control of most of the world’s rare minerals. This economic interest is combined with security concerns, as D. Trump declared that “for purposes of national security and freedom throughout the world, the United States of America feels that the ownership and control of Greenland is an absolute necessity”[13]. Such declarations have sparked debates and concerns on the status of northernmost borders.

Border discussions

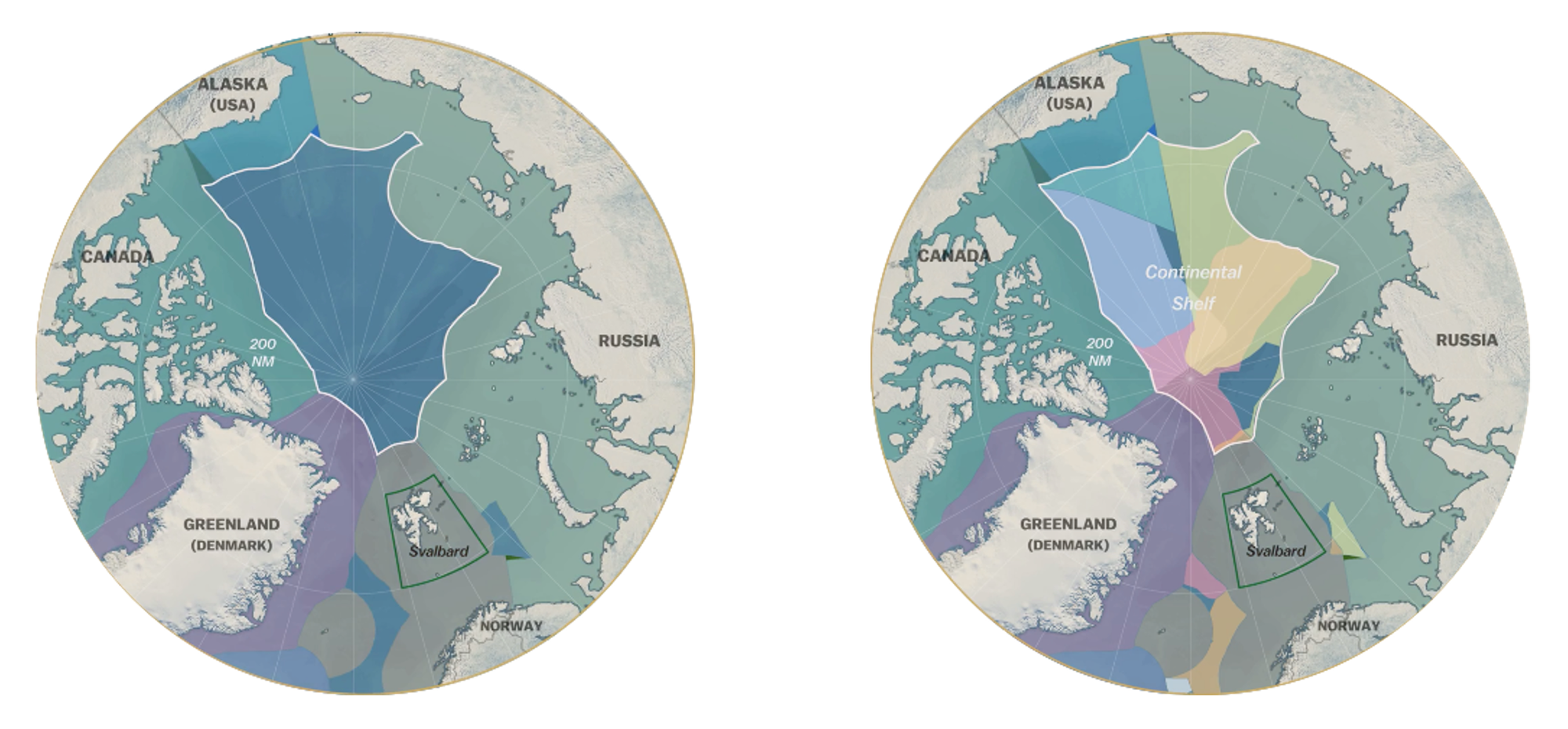

The Arctic is increasingly present in the international arena since border discussions are becoming vital for the Arctic states. Delimiting the zone in which each nation is sovereign to exploit the underlying natural resources is key to prevent competition or resource wars in the region. While terrestrial borders in the Arctic are well delimited, this is not the case for maritime spaces and particularly with regards to the continental shelf. Countries are submitting continental shelf claims to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (UNCLOS), but “problems arise when claims overlap, as they do in multiple cases here”[14]. Climate change has uncapped the decisive question of assessing the limit of each nation’s zone of exploitation, which is vital since “without well-defined boundaries, the possibility of conflicts over the right to utilize resources increases dramatically”[15]. In fact, there are currently “four ongoing territorial disputes in the Arctic”[16]: the Northwest Passage and the Beaufort Sea (between Canada and the US), the Lomonosov Ridge (between Canada, Denmark, and Russia) as well as the Hans Island (between Canada and Denmark, which was recently resolved). In addition to disputes among nation-states, the de-peripheralization of the region also raised the question of indigenous peoples’ rights and claims over Arctic land. Indigenous communities reunited as part of the Inuit Circumpolar Council[17], are contributing with their perspective to border discussions over the Arctic region. In some cases, domestic tensions have risen over the control of the Arctic space, as it is, for instance, the case in Alaska where the United States Fish and Wildlife Service had requested the creation of an indigenous sacred site recently refused by the White House[18]. Finally, border discussions have also led to a visual de-peripheralization of the Arctic, whereby boundary claims are illustrated via cartographic representations that place the Arctic at the center of the planisphere, hence removing the region from the graphical periphery where it has traditionally been relegated.

Conclusions

Undeniably, climate change is modifying the Arctic and the political understanding of its importance, as the melting of its permafrost consequently renders the Pole North more accessible and exploitable and increases interest in the region. Therefore, the Anthropocene can be considered as shaping global perceptions of the Arctic, both in terms of untapped economic opportunities and border discussions that are putting the Arctic at the forefront of recent political discussions.

Nevertheless, while recognizing the influence of climate change on Arctic diplomacy, there are also counterarguments to the idea of an Anthropocene-led de-peripheralization of the region. Given the Arctic history, the very idea of a de-peripheralization may seem ill-suited, and the Anthropocene argument too limited to explain the position of the Arctic in the global scenario. Firstly, applying the de-peripheralization idea to the Arctic region can be seen as ill-suited given the Arctic’s long record of exploration and militarism that the de-peripheralization argument might fail to recognize. To assert that the Arctic was “long neglected”[19] and that countries are only now understanding the geopolitical potential of the region reflects a limited vision of the Arctic’s history, which is marked by the quest toward the Northwest and Northeast passages, its strategic importance during World War II serving as a supply route for the Allies, and during the Cold War given the mutual perception of threat or supposed risk of invasion through the ice of the Arctic by the two superpowers. Similarly, the argument of an Anthropocene-led de-peripheralization of the Arctic has to be complemented by the awareness that there are factors other than climate change contributing to the increased interest in the region, in particular, linked to recent military build-ups by Russia as a reaction to its international isolation or by NATO, and in particular the United States, leading to an increased military presence in the region.

The views and opinions expressed in this paper are the personal views and opinions of the author and they do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation that the author works for.

Bibliography

O.A. Anisimov, D.G. Vaughan, T.V. Callaghan, C. Furgal, H. Marchant, T.D. Prowse, H. Vilhjálmsson, J.E. Walsh, “Polar regions (Arctic and Antarctic). Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change”, M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 653-685, 2007

G. A. Backus and J. H. Strickland, “Climate-Derived Tensions in Arctic Security”, Sandia National Laboratories, 2008

G. Chen, “China’s emerging Arctic strategy”, The Polar Journal, 2012

J. F. Colmeiro, “Peripheral Visions/global Sounds: From Galicia to the World”, Liverpool University Press, 2017

M. Descamps, “The Ice Silk Road: Is China a “Near-Arctic-State”?”, Institute for Security and Development Policy, 2019

G. Heggelund, E. Lamazhapov, I. Stensdal, “China’s Polar Silk Road: Long Game or Failed Strategy?”, The Arctic Institute, 2023

K. Keil, “Spreading Oil, Spreading Conflict? Institutions Regulating Arctic Oil and Gas Activities”, The International Spectator - The Italian Journal of International Affairs, 2015

C. Lu, “Why Is Trump So Obsessed With Greenland?”, Foreign Policy, 2025

R. A. McVey, “Russian Strategic Interest in Arctic Heats Up as Ice Melts”, LSE Ideas, 2022

D. R. Rothwell, “The Arctic in International Affairs: Time for a New Regime?”, ANU College of Law Research Paper No. 08-37, 2008

R. Winther Poulsen, “What Does Trump Want in Greenland?”, Foreign Policy, 2025

Bibliography - Websites

Arctic Portal, “Main themes identified for 5th International Arctic Forum”, 2019: https://arcticportal.org/ap-library/announcements/2091-main-themes-identified-for-5th-international-arctic-forum

J. Harris, “The Arctic - Russia’s plans for the world’s newest ocean”, Vox, 2018: https://www.vox.com/a/borders/the-arctic

Inuit Circumpolar Council: https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/

National Geographic Society, Definition of anthropocene, 2023: https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/anthropocene/

The Arctic Review, “Challenges – Territorial disputes”, 2022: https://arctic.review/challenges/territorial-disputes/

The White House, “Unleashing Alaska’s Extraordinary Resource Potential”, 2025: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/unleashing-alaskas-extraordinary-resource-potential/

Bibliography - Figures

Figure p.1: Map of the Exclusive Economic Zone and Map of the Extended Continental Shelf Claims, in J. Harris, “The Arctic - Russia’s plans for the world’s newest ocean”, Vox, 2018: https://www.vox.com/a/borders/the-arctic

Figure p.2: The Arctic Route, Christensen, 2009, in J. G. Alves Solares, L. Gimenez Cerioli, B. Lersch, A. Piffero Spohr, J. da Silva Höring, “The Militarization of the Arctic: Political, Economic and Climate Challenges”, UFRGS MUN Journal, Vol. 1, 2013

Figure p.3: https://arcticportal.org/maps/download/maps-arctic-council-member-states-and-observers/3539-arctic-states

[1] O. A. Anisimov et al, 2007, p.656

[2] J. Harris, 2018

[3] J. F. Colmeiro, 2017, p.69

[4] National Geographic Society, 2023

[5] D. R. Rothwell, 2008, p.1

[6] Arctic Portal, 2019

[7] M. Descamps, 2019

[8] G. Heggelund, E. Lamazhapov, I. Stensdal, 2023

[9] G. Chen, 2012, p.362

[10] K. Keil, 2015, p.87

[11] R. A. McVey, 2022

[12] R. Winther Poulsen, 2025

[13] C. Lu, 2025

[14] J. Harris, 2018

[15] G. A. Backus and J. H. Strickland, 2008, p.25

[16] The Arctic Review, 2022

[17] https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/

[18] White House, 2025

[19] D. R. Rothwell, 2008, p.1