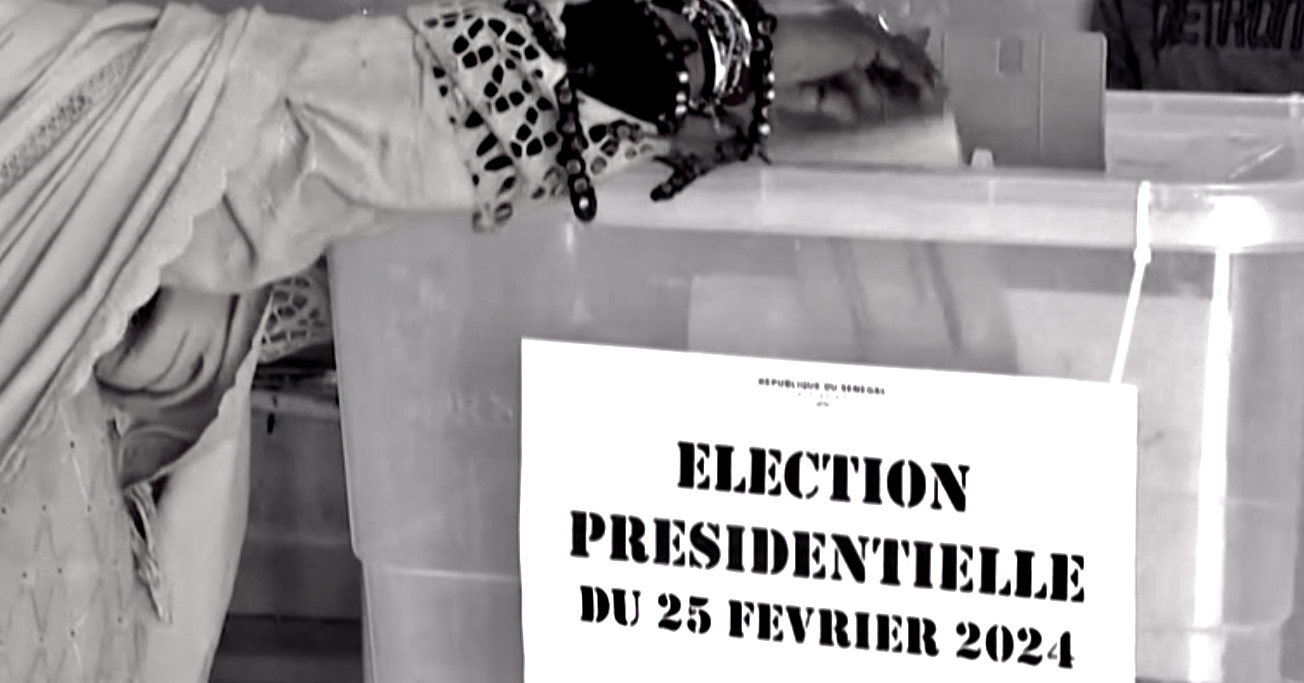

The Senegalese presidential elections held on the 24th of March 2024 achieved a historic result, marking the third “alternance” in the country and thus emphasizing Senegal’s posture as a bastion of democracy in the Sahelian and West African region[1]. Bassirou Diomaye Faye becomes the fifth President, marking a turning point in Senegalese politics. Faye has been presented as the Pastef candidate (“African Patriots of Senegal for Work, Ethics and Fraternity”, formerly dissolved in July 2023) by his mentor Ousmane Sonko, who could not run for office because of his double conviction for defamation and corruption of youth[2]. The duo Faye-Sonko, both released from prison just ten days before the elections, has defeated the main opponent, Amadou Ba, the Benno Bokko Yaakar candidate (the former ruling coalition), winning with the 54,28% of the votes in the first round. Faye nominated Sonko his Prime Minister a few hours after his official investiture.

Precedent turmoil

The elections were a democratic success despite the saga that preceded them. In February, former President Macky Sall attempted to postpone the elections, a move that was seen by many as an institutional coup and threw the country into turmoil. The process initiated by Sall and subscribed by the National Assembly (where opposition MPs did not take part in the vote, since they were escorted out of the building by the police) has been then blocked by the Constitutional Court. The latter, in an act described by many analysts as bold, categorically called for elections to be held before the end of Sall’s mandate (beginning of April). Sall abided by the ruling and released the opposition leaders Sonko and Faye from prison through an amnesty bill. The succession of these dramatic twists and turns crystallized in the confrontation between the nineteen selected candidates. Among them have emerged Faye and Ba, pulverizing all others – including the “political dinosaurs” such as the veteran Idrissa Seck (0,90% of the votes) and the former Dakar mayor Khalifa Sall (1,56%).

Elections analysis

Looking at the Senegalese presidential elections’ history, winning in the first round is quite ordinary. There have only been two exceptions: in 2000, with Abdoulaye Wade's victory against the outgoing president, Abdou Diouf, marking the end of the Senghor-Diouf era, and in 2012, with Macky Sall over his rival (and former mentor) Wade. Two significant exceptions, however, since they were the two moments of “alternation” in Senegalese power. Today marks the beginning of the Pastef’s era: an opposition party that, for the very first time, won in the first round.

Faye’s victory occurs within a turnout rate of 61.3%, out of the more than 7.3 million registered voters - that, however, makes up only 41% of the total population (with an average age of 18). Although this turnout can be seen, in absolute terms, as modest, it is within the average of Senegalese presidential participation rates[3]. Moreover, it is well known that the hard core of the Pastef electorate are the younger generations (although they are not exclusive – also counting a quieter middle class).

Voting preferences were evenly distributed. Faye won in the most populous and urban areas of the country: the entire coast, from Saint Louis to Zinguinchor, passing through Dakar and its surroundings and the center-west. Ba, on the other hand, won in the more peripheral regions, i.e., the inland center and the eastern departments.

Pastef program and approach.

Faye was elected on the principle of a break with the past, with a program described as sovereigntist, progressive, and pan-Africanist. On the other hand, Faye had underlined his adherence to existing institutions and administrative apparatus, which have demonstrated the attachment to the Republic by preventing the postponement of the elections.

In his first presidential addresses, Faye announced his priorities: among them, the fight against corruption; youth employment; purchasing power; the electoral and judiciary reforms. The Pastef programme entails radical reforms, such as the renegotiation of contracts for the exploitation of natural resources (fish, gold, hydrocarbons) and the overall re-balancing of relations with the main foreign partners, with the abolition of “subordinated” relations, aiming the construction of an endogenous-based economy.

However, Sonko and Faye have progressively toned down their intentions with respect to some of their main initial proposals, such as the exit from the CFA franc, declaring themselves in favor of the on-going discussions (since 2019) on the Eco currency at the ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) level; or, possibly, at the UEMOA (West African Economic and Monetary Union) level[4], excluding the role of France. Similarly, they reassured bilateral and multilateral partners and private investors, ensuring that “Senegal remains a welcoming country for all” and “will remain the friend and reliable ally of any partner that engages in virtuous, respectful and mutually productive cooperation” (that arguably includes France, one of Senegal’s main partners).

On April 5th, Sonko announced his new government, which includes twenty-five Ministers and five State Secretaries. Key Ministers are Pastef executives. The Interior and Defense portfolios have been assigned to two army generals. Moreover, out of thirty people, only four are women (including Yassine Fall, Minister of Foreign Affairs and African Integration, and Kady Diene Gaye, Minister of Youth, Sport and Culture). Senegalese Feminist movements have already underlined the gender gap, signed a petition, and further observed that the former “Ministry for Women, the Family, Equity and Community Development” has been replaced by the “Ministry for the Family and Solidarity”.

Senegalese foreign policy in the region

The new President Faye has been officially appointed on the 2nd of April in Diamdianio. Several African heads of state and institutional figures have been invited[5]. Among them, the Guinean President and the Presidents of the parliaments of Burkina Faso and Mali have been acclaimed by the public.

Although some aspects of Pastef’s programme seem to flirt with the foreign policy approach of the new Alliance of Sahel States (ASS, formed by Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger)[6], profound differences must be drawn. Their (partial) presence at the ceremony underscores the new Senegalese administration’s willingness to pose in a conciliatory manner and open to dialogue, to promote democracy among the ASS and try to convince them to re-integrate ECOWAS.

Senegal’s foreign policy actually stands out for its neutral position on international matters, which led it to pose as an important diplomatic mediator and actor despite the country’s relatively small size. Moreover, beginning with Wade’s Presidency (2000-2012) – and even more so with Macky Sall’s (2012-2024), Senegal progressively diversified its external economic partnerships, adding to its four traditional pillars (France, US, Morocco, and Saudi Arabia) emerging partners such us, among others, China, UE, Turkey, and the Emirates. On the other hand, this international practice has sometimes led Senegal to take assertive stances, especially about regional relations[7]. However, in the current scenario, one might think that if the new Senegalese leadership remained true to the expectations of the Pastef electorate, other Sahelian audiences might start looking at Senegal as an example, and the realization that an élite changeover can also come through a democratic path could fuel discontent towards the autocratic approach of the military juntas ruling in neighbouring countries.

The (double) enigma

In this context, two big questions on the horizon concerning the relationships of four men: the losing duet Sall-Ba, and the winning one, Faye-Sonko.

Diomaye Faye, completely unknown to the public until a few months ago, is elected at the direct behest of Sonko. Not that Faye was not involved in the construction of the Pastef project. Senegal's youngest president (44 years old), first polygamous head of state; apparently shy; with eleven months in pretrial detention behind him; former tax inspector (like Sonko), a law degree from Cheick Anta Diop University and an ENA alumnus, he participated in the creation of the party in 2014 and in 2022 became its secretary general. As already mentioned, a few hours after taking the oath on “God and the Nation”, he appointed Sonko as his Prime Minister. A two-tier system could thus be envisaged (at least, a de facto one), regarding which one may wonder if the premier will take over the presidency. That would be a first for Senegal, where the only two-tier parliamentarian regime dates to the very first Senghor administration[8]. Similarly, the question arises as to whether the vaunted institutional reforms would include a true decentralization at the decision-making level; or whether it will simply be a relocation of the implementation of decisions taken at the central level.

On the other hand, the relationship that linked former President Macky Sall and his candidate Amadou Ba, starting from the latter’s appointment as PM to the Presidential election campaign, remains mysterious. Beyond Sall’s attempt to postpone the elections, which certainly did not help the coalition Benno Bokko Yakaar, the former President does not seem to have particularly facilitated his nominee. Oumar Sow, a member of Sall’s party (Republic Alliance), had even stated that “Amadou Ba has been treated despicably […]. Resources were made available to plunge him into Macky Sall’s orchestra so that his candidate would lose the presidential elections”. It is not clear whether we assist in a big misunderstanding or a series of clumsy and reckless actions. The latter seems odd, given Macky Sall’s political stature and experience. One could conjecture a hidden machination by the former President, possibly including the participation of Sonko, aiming at the future peacefulness of Sall himself; or a statesmanlike vision for the future stability of the country… In all cases, Sall is about to move to Marrakesh, and one of his new responsibilities, the Special Envoy for the Paris Pact for Peoples and the Planet position, awaits him. A position that will hopefully enhance his robust advocacy, started during his AU Presidency, on multilateral reforms for the strongest agency of developing countries.

Conclusion

Senegal’s future remains to be uncovered. Various scenarios open up, depending on the degree of balance the government will be able to maintain between electoral promises and its related “populist” agenda, internal and external pressure from interest groups, and economic pragmatism. The Pastef electorate will probably remain key and one of the main barometers of the new government’s decision-making. Hence, the degree of radicalism of the new administration remains an unknown to be untangled in a range of shades: from the “everything must change for everything to remain the same” scenario to extreme positions (be they vis-à-vis external partners, surfing the decolonial wave of anti-Françafrique, or be they religiously motivated conservative reforms), passing through a possible “third way”, against which the government will be able to keep its cornerstones without disrupting Senegal’s economic and diplomatic assets. In this sense, the Senegalese experience could continue to provide a worthwhile case of democratic turnover; thus, following an extremely delicate path.

[1] It should be added that neighboring Cape Verde, in a less ostentatious manner, also presents a democratic and coup d’état-free succession.

[2] Sonko has been sentenced for defamation to two months’ suspended prison, and to pay compensation to the former Minister of Tourism Mame Mbaye Niang, accused of embezzling public funds by Sonko. On the other hand, the second (bigger) charge was of rape. The accusation was brought by Ndeye Khady Ndiaye, a young woman running a beauty salon where Sonko used to go (also during COVID-19). After a long and controversial trial, Dakar criminal court sentenced two years imprisonment for Sonko on a charge of “corrupting youth”, thus acquitting him of rape. The “corruption of youth” consists of encouraging the debauchery of a person under 21.

[3] More precisely: a turnout of 66.2% in the 2019 first round; 51,6% in the 2012 first round; exceptionally, 70.6% in the 2007 first round; 62% in the 2000 first round.

[4] UEMOA members are the following: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and Togo. UEMOA is distinguished by the common use of the West African CFA franc currency (XOF), which has a fixed exchange rate to the euro. The CFA franc is criticized because it tied UEMOA members to their former colony, France, since half of the foreign exchange reserves are deposited in the French Treasury, and because it binds their monetary policy to the European Central Bank.

[5] Namely, the President of Mauritania (current President of the African Union); the President of Ghana; The Gambia; Sierra Leone; Guinea Bissau; Cap Verde, Nigeria; the vice-President of the Ivory Coast; the Prime Minister of Morocco and Rwanda; the President of the AU Commission, ECOWAS Commission and UEMOA Commission.

[6] In January 2024, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have withdrawn from ECOWAS, announcing the creation of a new regional organization, the Alliance of Sahel States. The three countries are all run by coup military juntas, presenting a radical rupture with the past, including their relations with the former colonial power, France. For the moment, they seem supported by public opinion, in line with a strong decolonial approach and the “let’s try the next one” philosophy.

[7] Examples are Senegal’s interventions (within ECOWAS) in neighboring Gambia and Guinea Bissau. Senegal, for example, has played a major role in the takeover of the Gambian President Adama Barrow, in 2017. Its “hegemonic” approach must first be understood in terms of internal politics and stability, related to the southern region of Casamance. On this, see Vincent Foucher’s works. Another example, which didn’t come to fruition, was Senegal’s explicit support within ECOWAS for an armed intervention in Niger after the coup d’état in July 2023.

[8] The two-tier parliamentarian regime ended in December 1962 with the political crisis opposing the President Senghor and the Prime Minister (Président du Conseil du gouvernement) Mamadou Dia, thus marking the beginning of the presidential system. The PM office was later reinstated by Senghor himself in the 1970s, within a hyper-presidential system. The office was then repeatedly revoked, most recently during Macky Sall’s presidency, who recently ruled without PM from May 2019 (end of Dionne government) until the nomination of Amadou Ba, in September 2022.