In the West, much is being written about the spread of the coronavirus. During the last months, we visited refugees and IDPs camps in Mali and Niger to witness the conditions they live in, and broaden the reflection on how these marginal places, forgotten in their invisibility, exist in States that are increasingly controlling their populations, and what could be the impact of coronavirus contagion in the camps.

As Western liberal democracies are shaken by the restriction of movement and social distancing, many have questioned the powers vested in the state to limit freedoms and the necessity to rethink the relation between the individuals and the societies they inhabit. But what happens to those who didn’t have this freedom not even before the crisis? And, with a virus that transcends borders, what could happen after the crisis?

There are peripheral spaces, like Mali and Niger, which struggle to make headlines, where hundreds of thousands of displaced people from the lower social strata live in precarious conditions, uncertain about their future, but with the profound fear that if the virus would reach these forgotten corners of the globe it would be a hecatomb. While their governments are implementing stricter measures and making awareness campaigns on how to properly wash hands, these hundreds of thousands of people barely have access to food, let alone running water.

With the escalation of violence in the Sahel, the number of IDPs grew exponentially in the last eight years. According to the latest UN Report on the Movement of the Populations from February 2020, there are more than 218.000 internally displaced (IDPs) in Mali out of which 54% are women and 53% are under 18 years old. In Niger, there is about the same number of IDPs, roughly around 200.000 people, and more than 780.000 in Burkina Faso. Crunching numbers, including refugees, asylum seekers and returnees in the three countries, we reach a staggering total of more than a million people living on the edge of society in the Sahel.

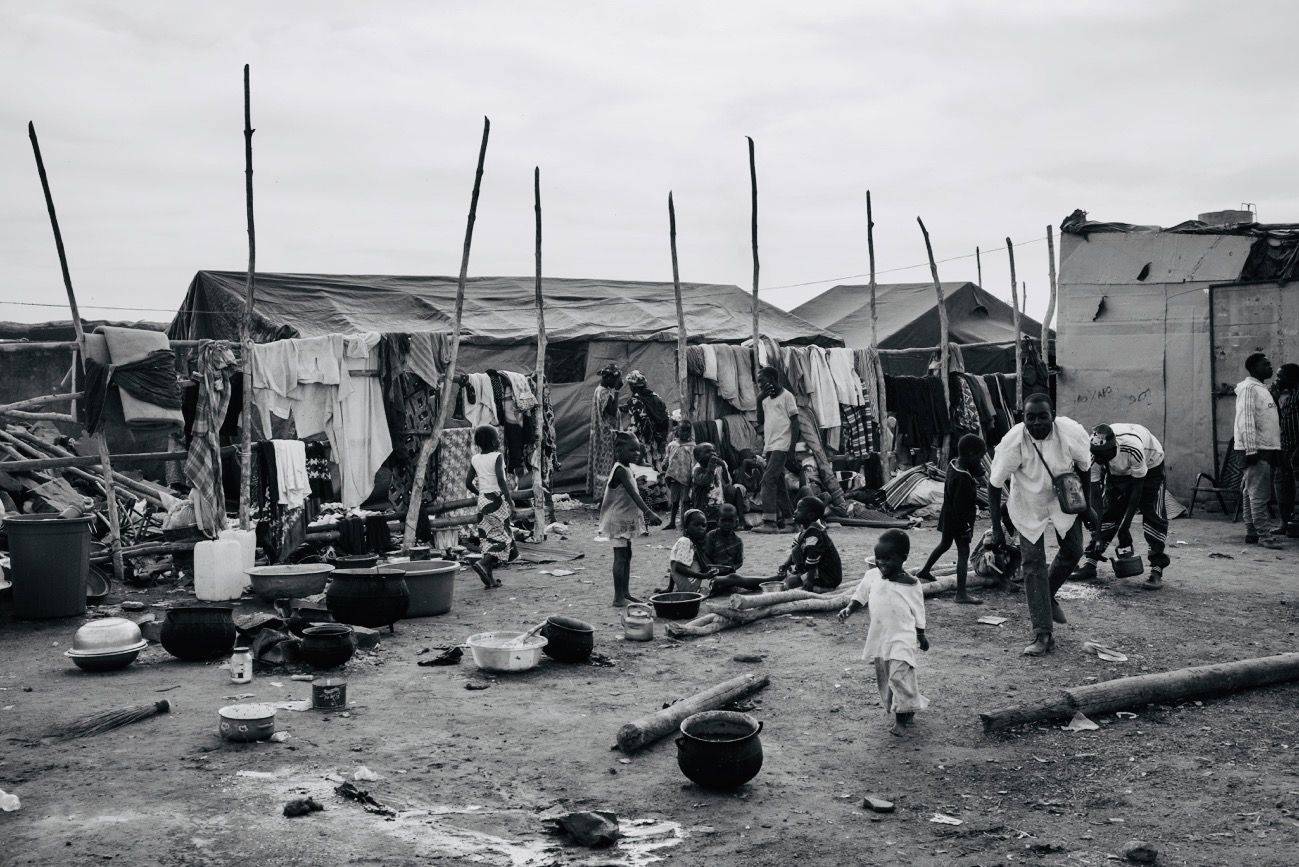

Our first visit starts in Faladié, on the outskirts of Mali’s capital Bamako, where a camp has been set up in a landfill. The smoke plumes from burnt garbage are visible from afar, intoxicating the surroundings. Trash epitomizes the building block of people’s daily lives, as small children play with it, cows and goats ruminate it, tents are made of shreds of tossed canvas and burlap sacks. The people living in the camp are Fulani who fled communal violence in the Mopti region in central Mali. They started to arrive in December 2018, as violence pitched nomadic Fulani herders and settled Dogon farmers against each other. The ones that are registered and thus receive social protection are a little bit over one thousand people (80% of which are women and children) but the actual figure is said to be closer to ten thousand.

Perpetuation of the bare life is assured by donations and cadeaux from local associations and international organizations, dispatching from time to time bags of rice and sanitary kits for women. “The government assists only 3%-5% of the people living here, providing food and medical coverage”, says a local spokesperson, “This creates tensions among the beneficiaries and those who receive nothing”. In order to survive, some collect trash to get 100 CFA (0.15 Euro) for a kilo of plastic, others go into town to inflate the ranks of beggars, while the luckiest do some small trade to buy cattle feed.

The president of the association that manages cattle sales in Faladié, a well-known Fulani man from Mopti, gave the land to the IDPs to have a place where to settle temporarily. As there are no sanitary facilities, they relieve themselves in the open air or they have to pay 25 or 50 CFA to use a private toilet, depending on the need. Water is also a rare commodity and due to the absence of a water system, they are obliged to buy 20 liters tanks for 75 CFA each, outside the camp.

When night falls, delinquents visit the camps to sell drugs and exploit women for sex, often the only source of revenue for young women. But also, sexual violence is a common practice, even though it remains a taboo topic. “Nobody will ever admit that a girl has been raped, and as women themselves feel ashamed, they don’t talk about it. But then, at the age of 14 or 15, they get pregnant, so everybody sees that they have known sexual intercourse”, the local spokesperson said. Most of them have trouble sleeping. And when they wake up, they still have to live with insecurity and the ghosts of past traumas.

The camp of Sénou, in the suburbs of Bamako, hosts around 850 Fulani in 200 plastic tents who fled from the Mopti region in the center of Mali. A lot of their stories are similar. Around the end of 2018, the Dogon militia, Dan Na Ambassagou ( “hunters who trust in God”) attacked their villages, and when they alerted the Malian Armed Forces (FAMa) to ask for protection, the latter reportedly replied either “It will be all right” without ever showing up, or asked a payment between 150.000-200.000 CFA per pick-up. Under a tent, 71 children from 5 to 8 years old learn how to read and write a few hours per week. Fulani older women, who are usually in charge of selling milk, have nothing to do, so they wait, until somebody provides them a meal.

The calculation of the chances of survival is brutally simple: fleeing or dying. And the fate of those who decided to stay in their villages was inevitable. At the end of March 2019, Dan Na Ambassagou attacked the localities of Ogossagou and Welingara, burning the villages to the ground and leaving behind 160 Fulani dead. After the massacre, the FAMa established a post in Ogossagou to deter any further violence among the Fulani and the Dogon communities, which was dismantled on 13 February 2020. The day after, a Dogon militia surrounded the village, chased civilians into the bush and killed 35 of them, mostly men.

Jihadist groups managed to largely – but not exclusively – recruit Fulani herders leveraging on their frustrations over insecurity, marginalization, state absence, abuses by security forces and self-defense groups and competition over natural resources. In turn, the sedentary Bambara and Dogon communities, formed self-defense groups to protect their villages from the attacks of jihadists armed groups. Violence has thus taken hybrids forms, intersecting self-defense and insurgency under a jihadist umbrella.

The expansion of activities by the Islamic State Greater Sahara (ISGS) and Al-Qaeda affiliated JNIM in the so-called tri-border area (Mali-Niger-Burkina Faso) has significantly taken a heavy toll on the population. In the region of Tahoua, bordering with Mali to the West, Niger has been hosting Malian refugees since the outbreak of conflict in Northern Mali in 2012. In the hosting area (Zone d’accueil des réfugiés, ZAR) of Intikane live more than 30.000 people, including Malians refugees coming from Gao, Kidal, and more recently Ménaka, and Nigerien IDPs that fled from Agondo, Chinewarene, Assaqueyguey following the deterioration of the security situation in the region. The ZAR is not a regular refugee camp, but an area of several square kilometers where hangars stand out as mushrooms in the midst of stretches of rusty red sand as far as the eye can see. Humanitarian associations set up a school at the center of the camp for more than 2600 children, mostly Malian refugees and a few hundred locals. A dozen women cook for the pupils two meals per day, breakfast and lunch, to avoid long journeys in the desertic land and reducing school absenteeism. In this area, finding a source of revenue is extremely hard for the refugees and the IDPs. There is not much to do, as it’s impossible to cultivate the land and they own very few heads of livestock. Their days go by, wondering to find some wood to cook and eat. The men once a week used to work in the cattle market, but the authorities shut it down as they suspected it to be a recruiting spot for jihadists groups. This hasn’t stopped some of them to be involved in trafficking or joining the CMA (Coordination of Azawad Movements, a coalition of Tuareg independence and Arab nationalist groups), the JNIM, and more recently ISGS.

While on one hand the Malian and Nigerien governments are adopting policies of containment, following to the letter Western precepts (in continuity with the patterns already established in the fields of counterterrorism and migration), aimed at changing people’s habits and way of self-sustaining, on the other, there are non-places inhabited by people who have been abandoned twice. Forsaken by state institutions during the conflict and neglected afterwards, a stone’s throw away from the capitals.. In these fragile contexts, plagued by intercommunal violence, jihadist expansion, poor governance, and corruption, the threat of the spread of coronavirus, could be the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Acknowledgements

All photos by Nicolas Réméné

Nicolas Réméné is a Bamako-based freelance photojournalist. He covers social and environmental issues and regularly collaborates with the international press (Le Monde, Libération, Le Point) institutions and NGOs (UE, UN, CICR, GIZ, ENABEL).