Following the publication of his latest book on France’s Wars in Chad in the 1960s and 70s with Cambridge University Press, in this interview Nathaniel delves into how the provision of military aid to fragile states may further entrench autocratic rule and lead to further instability down the line.

The famous statistical analysis conducted by economists Collier, Hoeffler and Rohner has suggested that from 1965 to 1999, former French colonies were only a third as likely as other comparable African countries to experience a civil war. They attributed this difference to the security guarantee that France provided to many of its former possessions. This book aims to trace the role France played in the downward spiral that gripped Chad from its independence in 1960 to the rise of Hissène Habré’s dictatorship in 1982. The first example analysed in the book seeks to show how the French interventions, while militarily successful, failed to establish the kinds of state legitimacy necessary to ensure peace. On the contrary, Powell argues that the first French operation encouraged the Tombalbaye regime (1960-1975) to further retrench, which led to a subsequent rebellion later on. French protection meant that the Tombalbaye regime no longer had much incentive to reach out to Chad’s marginalized communities, and the militia policy undermined efforts to reestablish state administration.

The second French intervention in 1978 aimed to stop Libyan-backed rebels from seizing the country’s capital. French officials contributed to getting Libyan forces out of the country, only to find themselves backing a fractious coalition government incapable of defending itself. This set the stage for seizure of power by Hissène Habré, which went on to become one of postcolonial Africa’s worst dictators (1982-1990).

This book is illuminating in many respects: it is certainly necessary to fill a gap in our understanding of the history of French postcolonial practices and the formation of the Chadian state that we know today. But the book is all the more relevant in that the Chad examples analysed by Powell could enlighten our understanding of current security practices in the Sahel and elsewhere.

1. What does the French intervention in Chad tell us about military interventions in general? To what extent and in what instances can we draw a parallel with the current conflict(s) in the Sahel?

It’s clearly hard to generalize on the basis of the two cases I cover in my book, but I did try to look at this question more broadly in a 2017 article I published in African Security on the recurring logic of French interventionism in Africa. It looks at patterns of both motives and impact of French interventions going back to the early 1960s. What I argue—and this comes out in the book too—is that the French desire for “stability” at any price has consistently led to a preference for autocratic or conservative political orders who can either maintain it or whose downfall threatens contagion elsewhere. The problem is that these political orders themselves—or their long-term effects—have often generated the very instability France has aimed to prevent. This has of course led to military interventions—France has been one of the most, if not the most, active military intervener in the world since 1960 (more than 50 in Africa, of which maybe 15 or so were major efforts to impose or restore state authority in various countries).

The effect of these interventions—including in Chad—has generally been negative in the sense of protecting or restoring governance systems which are inherently exclusionary and violent. French resource influxes have empowered security actors who have generally been unconcerned with human security/rights. More importantly, the protection afforded either by interventions or security umbrellas have removed incentives for leaders to broaden their constituencies or make efforts to seek legitimacy in peripheral spaces or in marginalized communities. You can see this dynamic at work outside of the Franco-African sphere—for instance following the American invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, or the US in Vietnam.

2. Do you believe that the presence of a wider array of actors in the Sahel compared to the Chad cases you analyse would complicate an understanding of power dynamics?

Certainly, and it also complicates the ability of France or any other intervenor to accomplish their aims in the absence of clearly-elaborated protocols for collaboration and joint-decision making. That isn’t in anyone’s real interest though, so don’t expect it anytime soon. On the other hand, this can, maybe paradoxically, remove some of the limitations that political leaders in places like Mali or Niger have faced from French pressure as their international resource base widens and they gain the ability to play off intervenors against each other in ways that allow them to maximize their strategic autonomy in otherwise constrained environments. This happened in Chad in the late 1970s and 1980s as countries like Libya, Nigeria, Sudan, and the US became deeply involved in Chad’s conflicts. This both drew in increased French military involvement and limited their influence at the playing table at the same time.

3. Let's go back to Chad and your book: as reported by Ben Taub and others, in 2019 Barkhane supported Déby's efforts to quell a rebellion in the north of the country by bombing rebel convoys for a period of four days. France is supposed to carry out counter-terrorism operations in the region against an enemy that is perceived as everybody's enemy and yet in this case they intervened to save Déby's rule. This was of course done to preserve a partnership with an ally that is perceived as necessary. What do you think this signals to other Sahelian leaders?

One of France’s “traditional” military roles has been, since 1960, to provide a security guarantee to their closest African clients. Failing to act in their defense carried a perceived credibility cost. That hasn’t prevented plenty of coups, but those were generally only successful against leaders who either had more troubled relations with France, or whom France did not view as strategically important. For instance, despite a French military presence in Chad, they allowed a coup against Hissène Habré to go forward in 1990 (bringing current president Idriss Déby to power) because they didn’t see Habré as a particularly cooperative client and preferred the alternative. To some extent, that logic has faded a bit, especially since the 1990s and the aftereffects of the Rwandan genocide. But the need to maintain or protect stable political orders remains, or has at least re-emerged in the past decade.

Déby’s relationship with the French has been troubled at times—especially in the late 2000s when he killed major opposition leader Ibni Oumar Mahamat Saleh, but since 2013 and the beginning of French military reengagement in the Sahel, he’s been a pillar of France’s regional strategy. Protecting him is thus very important—despite the unsavory nature of his regime—at least against armed efforts to overthrow him. As you noted, that’s the main reason for intervening. As for the signal it sends, it’s certainly an ambiguous one since they did nothing about the overthrow of Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta (IBK) in Mali last year (though why they did so is pretty clear—IBK was increasingly unpopular and not doing the job Paris was hoping he would do). I think the intended message was for N’Djamena, and possibly an unspoken down payment on future assistance of the kind we’re now seeing from Déby in the triborder region of Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso. It shows that Déby can deploy his best troops abroad without having to worry about getting overthrown at home. It also perhaps signals a broader French commitment towards those willing and able to follow through on a credible pan-Sahelian stabilization strategy.

4. Do you believe French leadership is aware of these ramifications? And historically with Chad, was it a lack of understanding of the long-term implications or a lack of willingness to sacrifice their regional strategy that led the French to continue supporting authoritarian regimes?

It’s sometimes hard to tell, but in my experience the private pronouncement of French officials aren’t often too far from their public ones. Certainly in the past, French officials have largely internalized a meta-narrative which sees their African friends—and behind them the French army—as necessary bulwarks against the ever-present threat of destabilization and regional collapse. In the past, the fear was about communism or anti-colonial nationalism or even “Anglo-Saxon” influence (which partly motivated French support for the Hutu supremacist regime in Rwanda). Today it’s jihadism. Just like the other phenomena, the narrative around jihadism tends to obscure its complicated nature and build on conceptual models which leave little room for nuance. This makes it easy to rationalize both the use of force and support for deeply problematic governance practices.

French officials are certainly aware of their clients’ abuses, but the response to this usually revolves around a) denial that external French aid exacerbates this problem, b) assertions that the French role mitigates this problem, and/or c) that however bad these guys might be, there is no alternative, or the alternatives are worse. I remember hearing one French official defending Barkhane’s record by pointing to the millions of euros spent by the EU on human rights training and insisting that we should differentiate between terrorist groups whose “essence” is to abuse human rights, and state security forces and governments. This of course highlights the analytical problem at the heart of French understandings of jihadist violence and threats to state authority.

On the other hand, I don’t think there’s a deeper awareness of the implications of this kind of strategy on the longer-term political trajectories of “target” countries. The problem though, is that even if there was, strategic, political, and bureaucratic impulses are short-termist by nature, and sometimes kicking the can down the road is the rational thing to do—i.e. yeah maybe this political setup will cause problems down the line, but a lot of other things will have changed by then too so there may be options for dealing with the fallout.

Support for leaders like Déby is also very much rationalized in the same vein as support for leaders like Mobutu in the 1970s and 80s—it’s either him or chaos. That might or might not be true, but the extent to which it is true is a direct result of how Déby has governed the country in the past 30 years.

5. In recent months, there have been increased calls for negotiation with armed groups in Mali. How much do you think France's response to this is hampering talks? Do the French have the power to effectively limit negotiations?

I think it would be hard for Sahelian governments to openly conduct the kinds of negotiations that say, the Americans are conducting with the Taliban, while the French are publicly opposed to such measures. [Just as the American have vetoed any Afghan rapprochement with the Taliban in the past, until they decided the time war ripe for talks; e.n.]. That doesn’t and hasn’t prevented declarations of intent or less formal backdoor-type approaches, nor has it stopped local arrangements from being put into place.

That being said, both the French and Sahelian governments—at least at the official level—tend to describe their jihadist adversaries in blanket terms which imply homogenous and ideologically uniform organizations. However, these groups are, as Alex Thurston has so eloquently analyzed in his recent book, fundamentally political coalitions which include a wide range of communities and personalities—and not simply hard-line jihadist combatants. The local elites connected to different jihadist groups (especially within JNIM I think) are constantly in communication with each other and with national-level elites—as well as between and among local communities where clashes between jihadists and ethnic militias are major drivers of local insecurity-eg between Dogon and Peul communities in central Mali.

The key to peace in Mali and Burkina Faso—and to only a slightly lesser extent in Niger—isn’t simply improving “governance” but is about building trusting political relationships between actors in the center and periphery which can really deliver the goods to people at the margins. Personal political relationships, which can then serve as a conduit for more durable service provision or representation / accountability at the national level is going to be far more effective at building state legitimacy than underfunded school and road building, combined with the odd airstrike or two. It also—and this I think is a critical point—forms the key plank of any effort to lastingly weaken the hold of jihadist political coalitions over larges swathes of territory. Undoing or reconfiguring these coalitions has to be the core of any political strategy. The only problem from, say, the French perspective, is that this can only be a Malian, Nigerien, Burkinabè process internal to those countries, states, and societies. Barkhane can’t do this, and in some sense it prevents this from happening.

6. How would you imagine these negotiations and could you give us an example with regard to your research into Chad? This is a particularly relevant question as presidential elections in Chad will take place this year.

Well, I think one thing the French are right about is that a lot of people may be placing too much hope on negotiations with jihadist leaders for a restoration of state authority and an end to insurgency—though they may be right for the wrong reasons. Leaders like Iyad ag Ghali or Amadou Koufa preside over potentially fissiparous coalitions and communities and conceivably don’t exercise the degree of control often attributed to them. This means, regardless of their intentions, they might not be able to hold to any major deal struck with them. Second, and relatedly, the biggest driver of insecurity and violence throughout the Sahel remains the abusive behaviour of state actors. Cutting deals with jihadists—unless accompanied by a substantial shift in the character of center-periphery relations, won’t address this fundamental problem, and may well only have a limited effect on local insecurity.

The Chadian example provides an illustration of how these negotiations could also backfire. In the mid-to-late 1960s, the Chadian government of president François Tombalbaye was facing a widescale rebellion which threatened to overthrow his regime. He asked for French military assistance and he got it. One of the key elements of his and French efforts to defeat the rebellion was to combine military pressure with negotiations targeted at undoing the political coalitions undergirding the rebellion. This involved offering posts in government and army, tax-gathering authority, or outright bribes to different rebel leaders or groups—often based on ethnic or personal criteria.

This actually worked pretty well in dividing the rebellion and substantially weakening it, but it didn’t address state violence which was at the core of the problem. The French military presence—and success over recalcitrant rebel formations—afforded a certain level of protection to Tombalbaye which removed most incentives for reducing state predation. It didn’t address local insecurity and this divide-and-rule approach generated a vast reservoir of resentment which later rebellions could draw from. In other words, negotiations bought short-term gains at the cost of a longer-term catastrophe.

Of course that’s not to say negotiations aren’t important—they’re indispensable for ending this current set of conflicts. The point is that negotiations-as-dealmaking is not the same thing as negotiations as a process for greasing the wheels of state transformation which would provide peripheral communities with more representation at the center, and better access to state services and material resources. With the French army guaranteeing the perennity of existing political orders though, I don’t see how these kind of transformations are likely to happen.

7. The way you describe Chadian elites post independence had me question whether we are getting it all wrong (!). European policy makers working on the Sahel are now coming to terms with this post-Pau logic of demanding accountability from their Sahelian counterparts. They are now implying that it is not just a matter of lack of capacity, but a lack of political will on the part of Sahelian elites. Don't you think that we are overestimating the role we have in the region? And if we truly do have a role as relevant as that of the French in Chad in the '60s and '70s, is there no way to also have an impact that is mindful of conflict dynamics and consequences of clientelism?

I don’t know if the role of intervenors is overestimated, but their effect is not well-understood. There’s a parallel between some hard-line critics of French/European/American involvement and the hopes of those intervenors themselves, who both expect some kind of linear relationship between outsiders who pull the strings and local actors who do the bidding of their paymaster. Intervenors—even those with the most leverage, often find that’s not really easy to do. Postcolonial Chad is a great example of this. France was Chad’s only patron, only major source of foreign aid, only significant external market, and only security guarantee to Tombalbaye’s regime in the 1960s. Yet, every step of the way Tombalbaye and his advisors consistently undermined French efforts to reform or restructure governance, replace corrupt officials, and redirect resources to marginalized areas. France simply couldn’t leverage their massive political and economic weight into political outcomes they desired—and this was at the height of French neocolonialism in Africa!

Today’s French officials and other intervenors encounter similar problems with substantially less relative institutional weight than they had 60 years ago. This suggests there are serious limits to what intervenors can achieve in terms of ending conflicts and restoring/creating the legitimate state authority needed for lasting peace. I also don’t think “political will” is necessarily the right way to frame the problem. It’s not so much a question of will, it’s a question of interests and the resource constraints which help to frame those interests. It’s still also a question of capabilities—who actually has the power to enact the kinds of profound transformations of state-society relations required to put an end to local insecurity and communal conflict?

8. Your book shows that military intervention cannot possibly work in fragile and fragmented authority settings. I know it's a big ask, but do you believe that having a more nuanced definition of fragile and fragmented state & imagining state legitimacy in a spectrum could give policy makers a better way to look at this and possibly imagine a less ambitious type of intervention that perhaps achieves less but also promises less?

I absolutely think that military interventions in settings like today’s Sahel are far more likely to cause harm than improve security in the medium or long term. I think it’s less a question of strategy and more a question of structure—resource influxes and a foreign military presence have major impacts on political incentives, political economies, security sectors, and state legitimacy in ways that are not likely to significantly change in response to shifting intervention strategies. So yes, I think in fragmented/failed/failing states (whatever moniker seems to fit the bill) international actors who look to improve security and stability need to be realistic about what can be achieved—and often these are very much at the margins.

At times those margins might matter though, at least to substantial groups of people even if it has little impact on the overall political situation. I’m thinking of properly resourced and delivered humanitarian assistance to displaced and other vulnerable people, allowing agricultural producers better access to European and other markets, targeted financial aid to help build justice, education, and health systems, and good offices to facilitate dialogue between warring parties. Ultimately though, international intervenors need to accept the hard truth that their actions may do more harm than good—regardless of intentions—and that some problems are not for outsiders to fix.

9. I personally struggle to see European actors intervene in ways that are even more remote and less ambitious than this. Even in our operations nowadays we struggle with sending troops (as is the case with Takouba); we don't engage in bilateral interventions but only through coalitions; deploy mostly air power or training missions. So I am pessimistic that we will be willing to do less than this — so I am trying to imagine doing better. Could conditionality mechanisms, stronger SSR, strong support to the judicial sector and Monitoring and Evaluation tools help us get a 'better return on investment'? Or are all strategies bound to fail?

I think military intervenors often have a tendency to overestimate their ability to positively influence events in the direction they’d like, and underestimate the likelihood of generating a wide range of negative unintended consequences. In other words, it’s a lot easier to make a problem worse than it is to make it better. But it’s also true that it’s easier to criticize ongoing efforts than to supply viable alternatives. My pessimism stems from the feeling that the structural impact of interventions unavoidably throw up obstacles to peacemaking, regardless of their actual intent, nature, or strategy.

For instance, one thing I would say in response to your suggestions above, is that interpreting local political conflicts in terms of “technical” issues amenable to technical/policy fixes (which is the ideological basis of SSR) is bound to fail. That doesn’t mean resources devoted to these things won’t benefit some people, or have an impact in one way or another, it’s just that those beneficiaries and impacts might not be those we are looking for.

To return to my book, the French embarked on their only full-fledged postcolonial statebuilding effort in Chad as part of their counterinsurgency effort there from 1969-1972. It failed precisely because it misidentified political conflicts and relationships as technical problems to be solved through “better administration” (hence its name, the Mission for Administrative Reform). I think one reason lessons haven’t really been learned from these kinds of experiences—which have their parallels all over the place, from Congo to Afghanistan—is that it’s hard to envision an alternative. Also, they’re “safe” kinds of interventions which are relatively non-controversial at the political level, and comparatively easy to get funding for.

I do think there are really hard limits that any kind of outside intervenor will run up against when trying to address conflict in the Sahel. Outsiders can’t make local states more legitimate, they can’t incentivize entire political classes to dilute their political/economic power, and they can’t usher in equitable economic development with magic fairy dust. They can keep regimes and political orders safe from specific kinds of threats, they can kill political leaders they define as terrorists, and they can pump lots of development funding into local economies/elite pocketbooks, but that’s not going to improve the livelihoods of tens of millions of people.

What is to be done? There’s no straightforward answer to that question. Western policymakers could definitely listen more to analysts with regional, rather than thematic, knowledge. This should help them get a better sense of what’s achievable. At the end of the day though, if we want to help, maybe we should pay a bit more attention to what those who aren’t parts of the Sahelian political elite have to say.

Nathaniel K. Powell, France's wars in Chad : military intervention and decolonization in Africa, Cambridge University Press, 2021. ISBN : 978-1-108-48867-9.

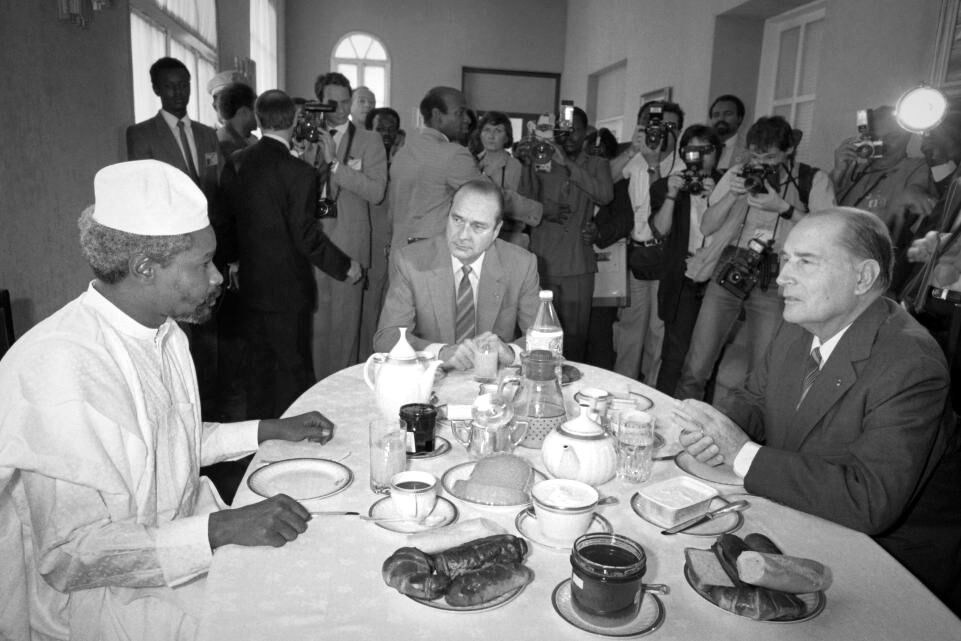

Cover photo: French president Francois Mitterrand (right) et prime minister Jacques Chirac (center) during breakfast with Chadian president Hissène Habré on 14 November 1986, during the 13th annual Franco-African summit held in Lome, Togo. © Daniel Janin /AFP/Getty Images