Introduction

Since 2013, when China’s President Xi Jinping launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Chinese government has paid special attention to Southeast Asia. Seeing itself rooted in the region, China exploited various tools of cultural diplomacy to legitimate itself as a “geopolitical actor”: in Beijing’s relationship with Malaysia in particular, a Ming Dynasty navigator, Zheng He, has been used to trigger positive yearnings about a Chinese peaceful return to power status. This blogpost will analyze a variety of representations – audiovisual materials, monuments, and official discourses – revolving around the figure of Zheng He and provided by various Chinese and non-Chinese, state and non-state actors, contributing to the promotion of the PRC’s geopolitical imaginary in the Southeast country.

Zheng He and the BRI’s discourse

In a video posted in July 2020 by Xinhua, the official state news agency of the PRC, frames of the city of Malacca (Malaysia) flow under the voice of China’s President Xi Jinping holding a speech at the headquarters of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in March 2014. The narrative is that the figure of the fifteenth-century Ming Dynasty navigator Zheng He and his legacy create a linkage between China and other countries, such as Malaysia: Chinese, Muslim-born, the “eunuch admiral” commanded seven naval expeditions to the Indian Ocean between 1405 and 1433. Sailed from East China and accompanied by its “treasure fleet”, he is said to have spent all his life travelling: the video states he reached more than 30 countries in Asia and East Africa, visiting the ancient trade hub of Malacca five times.

Throughout the Xinhua-story, it is said that Zheng He’s fleet “did not invade or plunder these places.” While images of memorials are broadcast, Xi Jinping’s words outline how “these trips left behind many good stories of friendly exchanges between the people of China and countries along the route”, pointing at the expeditions’ impact in the development of an “Ancient Maritime Silk Route”: at each stop, Zheng He paid a courtesy visit to the governor of the place and engaged in cultural exchanges with the inhabitants, while the artifacts the fleet carried were used to weave trade. In the end, a Chinese researcher connects Zheng He’s travels with Xi Jinping’s New Silk Road, stating that the story of Zheng He shared by “President Xi” encourages “to have a broad mind, promote harmony with all nations, and work hard to implement the Belt and Road Initiative.”

Nostalgia and global (re)ordering

Recognizing the above as one among many possible examples of systematic references to Zheng He’s story in Chinese elites’ discourses about BRI (“Full text of Premier’s”, 2015), one needs to ask oneself what role this revival plays in the PRC’s outlook on its place in global politics. Analyzing the phenomenon from the state leaders’ perspective, Lina Benabdallah (2021) examines the instrumentalization of nostalgia in Chinese foreign policymaking: acknowledging its effectiveness in reconstructing past stories and shaping narratives about the future, Benabdallah highlights how the PRC’s government associates figures (such as Zheng He) and major strategic platforms (such as the BRI) to positive affective experiences. By referring to when foreign sovereigns throughout the Indian Ocean accepted Chinese suzerainty, China’s comeback as a hegemonic seafaring power is branded.

The effect is obtained through techniques of spatial and temporal alteration, enabling emotional connections, advancing nonlinear orientation of time, and activating identity triggers. In the case analysis, Xi Jinping’s revival of Zheng He gives Chinese citizens a sense that they are descendants of a long-lasting civilizational power, at the pivotal moment of reemerging: by depicting the alleged peaceful nature of Zheng’s expeditions, Beijing has framed the BRI in terms of a new phase in a benign regional hegemony, which had its origins six centuries ago (Bijian 2005). Therefore, Chinese public opinion seems to believe in this narrative of global ordering, as the PRC’s approach to neighbouring cultures is portrayed as opposed to the aggressive “Western geostrategic theory” (Xu Qi, 2006). This imaginary creates a sense of “us versus them”, using the techniques of “Othering” to portray the West as fundamentally alien to Asian culture: a Chinese observer, Xu Qi, in 2006, declared that had the Ming Dynasty not outlawed maritime pursuits after Zheng He’s travels, Asian history would have taken a more humane course under Chinese dominance.

The Chinese state identity narrative intertwines the domestic and the international levels: as the BRI’s context suggests, the affective framing revolving around Zheng’s alleged legacy express a strategic aim to bolster legitimacy and shape new geo-cultural linkages between China and other countries. Researchers have attempted to clarify this view by using the concept of “Selving”: the practice consists of linking territorially distant places to a common past and present. Beyond conceptual definition, “Selving” plays on symbolism: the attractive appeal of a state’s culture is used to establish the country’s international standing. For instance, individuals from Malaysia who should not identify with the Ancient Silk Road, because geographically and temporally distant, find themselves celebrating China’s aspirations because of the CCP’s ability to include neighbouring countries in their narrative (Benabdallah, 2021). This has resulted in a polycentric network of non-state actors based in Malaysia, whose interests have happened to converge with the PRC’s (Hrubỳ & Petrů, 2019).

Malaysia: the Zheng He Cultural Museum as a medium of Chinese cultural diplomacy and Selving

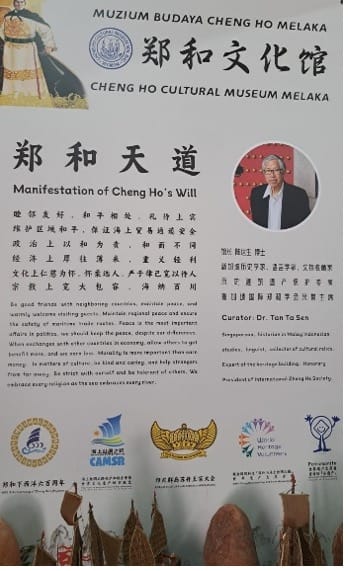

Therefore, the above helps overcome Agnew’s (1994) ‘territorial trap’: Chinese cultural diplomacy has managed to involve multiple agents that are influencing the state identity itself. In Malaysia, the presence of a robust and wealthy Chinese community, active in promoting Chinese culture and able to lobby the government, has promoted a web of projects contributing to the revival of Zheng He’s discourse: these initiatives are not directly planned by Beijing but by local actors who have elaborated on this narrative. It is the case of the Zheng He Cultural Museum, a private institution based in Malacca and run by Tan Ta Sen, a Singaporean Chinese scholar, and director of the International Zheng He Society.

The museum hosts artifacts allegedly related to the admiral’s voyages – Ming-era porcelains, models of his fleet and several maps exhibited to display the routes travelled (Lim, 2017) – and it is designed to diachronically show Chinese achievements before the European industrial revolution, as well as to follow the stages of Zheng He’s life: the museum narrative, constructed to be void of Western presence, suggests how Zheng He’s trade with Malacca stimulated the rise of a Malay sultanate and introduced Chinese migration to Malaysia (Tan, 2014). It implies the wide geographical reverberation of Chinese cultural influence, while delineating an area of irradiation, the Southeast region, and a centre, the PRC, from which it emanates.

To sum up, the galleries represent the civilizational goods the admiral brought to Malacca, such as cultural exports, technologies, and religion. As a matter of fact, an entire room is dedicated to the relationship between Zheng He, born to a Muslim family, and the “Islamization of Southeast Asia”. A bronze statue, which can be seen above, pictures him as a kid listening to his grandfather recounting his pilgrimage to Mecca and pointing metaphorically at it: a panel below explains how his relative’s stories must have taught him the passion for traveling. Further on, the curator explains the thesis that the navigator promoted the spread of Islam in Malacca and in the rest of the country: many stories about Zheng He’s building of Chinese-style mosques are reported. Since Islam is Malaysia’s national religion, by depicting the admiral as a “faithful Muslim” (Tan, 2014) the exhibition can be said to convey a sort of “Selving” narrative, as explained before: while overlooking China’s poor domestic record as regards the human rights of its Muslim population, the museum re-shapes the distance between China and Malaysia by making a vital trait of Malay culture depend from the encounter with a Ming Dynasty navigator. The two countries seem to share the same roots, a sort of pre-colonial “Asian-ness” to oppose to any sort of Western-centric construct (Wang, 1998).

Zheng He’s will: drawing conclusions on the political aspects within BRI’s symbolism.

As Tan Ta Sen highlights in the “Manifestation of Zheng He’s Will”, the accent of the exhibition is on diplomacy and collaboration. “Big-hearted ambassador”, the admiral is said to have adopted peaceful methods to promote the prestige of his country and create an atmosphere of harmony in international relations. Signs report how his “principles” can be conceived as a sort of counterpart of Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War”: in diplomacy, maintain regional peace and ensure good-neighbourly coexistence; in politics, value harmony as a good which relies on diversity; as regards economy, give more and get less; in matters of culture and of religion, be open and tolerant (Tan, 2014). These beliefs are said to constitute “a spiritual heritage Zheng He left to the world”, of inspiration for Chinese leaders: outlining how before the West came to Southeast Asia the area was already engaged in intra-regional trade, it conveys the idea of the Maritime Silk Road as a metaphor for an “Asian” way of mediating differences between nations, a non-hegemonic China-led order. Constant references to the present Xi Jinping’s Silk Road are made throughout the visit, as the initiative is seen as a revival of Zheng’s spirit: the Museum of Malacca has been visited by the top leadership from China.

But if Zheng He is perceived as a symbol of cooperation, one cannot but question oneself on the historicity of the image: such statements, in fact, stem from an irenic view of the expeditions, as sources report that he did not hesitate to apply brutal violence to display Ming power to considered peripheral states (Lim, 2017; Wong, 2014). To contribute to the narrative of a Zheng He’s theory of peaceful international relations, the museum exposes no records of Zheng He’s military exploits. Nostalgic instrumentalization in BRI’s discourses can explain the omitting of violence and the selling of an image of China as a non-colonial partner of Southeast Asia.

Aligning with Xi Jinping’s New Silk Road, the exhibition at the Zheng He Cultural Museum and the audiovisual materials herein analysed present a narrative that evokes nostalgia and fosters a sense of natural progression of civilizational heritage: through rhetorical techniques of spatial and temporal alteration, it appears to refer to a geo-cultural space characterised by an “Asian way” of development and collaboration, which allegedly dates to before the arrival of Western colonizers. It is a myth relying on the widespread presence of Chinese communities in the region: Zheng He is depicted as a symbol of cooperation, a trader whose legacy applies to international relations; a Muslim admiral who is said to have had a major impact on Southeast Asia’s culture, above all as regards the Islamization of the area.

The nostalgic instrumentalization within BRI’s discourses reinforces the image of China as a non-colonial partner in Southeast Asia, proving, overall, to be effective in forging an imaginary of proximity and shared identity: if relatively unknown to the Western public, it has already acquired remarkable importance in the region’s dynamics, managing to reshape perceptions on domestic and international levels.