Failure, debacle, fiasco. These are the most frequently used terms in the English language mediascape to assess the US and NATO performance following the Taliban's return to power in Afghanistan. Implicitly, perhaps inevitably, they look at the recent events from an American or Western point of view.

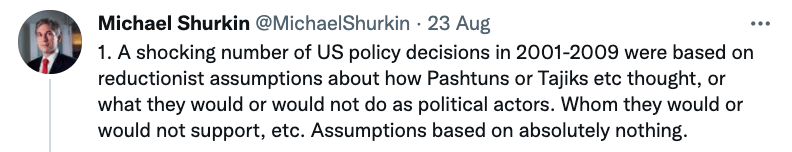

Many observers have already pointed out a general US/NATO inability to develop a solid, situated, first-hand, living knowledge of Afghanistan and its people beyond boilerplate tropes.

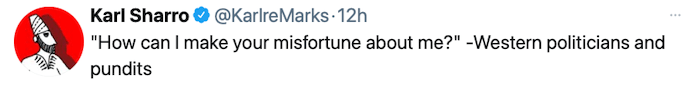

However, today's focusing on "our" failure, no matter how important, is itself a way of perpetuating a self-regarding gaze that is part of a wider problem.

There was a moment, a decade ago, when speaking publicly in a democratic Italian city about failure in Afghanistan drew the unwanted attention of the political office of the local police. Struck by this circumstance, I tried to pin down the psycho-linguistic roots of the term failure. I found that it starts early as fraud and self-deception. In other terms, some people, institutions just deliberately lie. The pundits start believing the stories they tell each other. Reams of regurgitated reports accumulate. Vested interests add momentum.

While this intuition has been confirmed in recent assessments, and finding out 'what went wrong' is an exercise worth pursuing further, we should go beyond talking about American failure or debacle or even defeat. The reason is simple and should not be eclipsed by self-indulgent jeremiads: a generation of Afghans was betrayed by their allies. This is how they say they have experienced it, this is how they expressed it many times, in many ways.

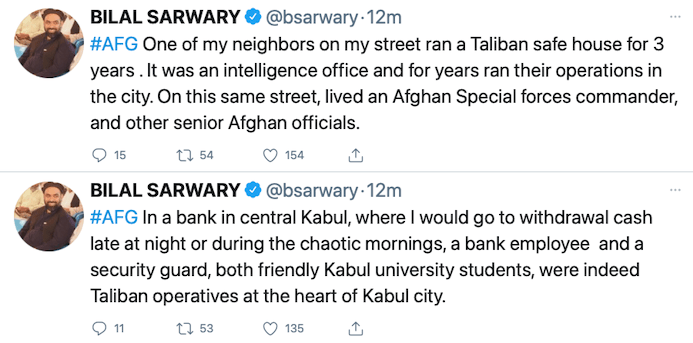

Not all of them, though. After years of strategic manoeuvring to extend their political and operational base, the Taliban had infiltrated Kabul to a high degree, as reported by the excellent Bilal Sarwary.

The Talibans' pervasive penetration and deal-making reached very deep into the Republic's institutions:

Graveyard of analogies

How many times, when reading about a crisis, you have read sentences like "Shaped like Texas, but twice as big, Mali is one of the poorest countries in the world"? Even the much-touted analogy of Afghanistan with Vietnam is, again, centred on the American point of view: keep the US constant, vary the ally and related débacle. An exercise not devoid of interest in itself. For example, a recent successful novel on the Vietnam war, The Sympathiser, by Viet Thanh Nguyen, resonates with the experience of some Afghan authors as they expressed it to me: “The author denounces that subtle racism that victimizes the Vietnamese in the narration of their own history. The author does not want to be pitied. He wants to not be silenced”.

But the comparison should at least be complemented with the other recent exit: keep Kabul constant, vary the superpower.

Gorbachev decided to pull the Soviet 40th army out of Afghanistan at the end of 1985, less than a year after becoming Secretary of the Communist Party. In the following three years they enacted a number of policies aimed at strengthening their ally institutions and broadening the political and social bases of the regime. The indecisive, weak Babrak Karmal was persuaded to resign as President, ushering in the younger and charismatic Dr Najibullah. The armed forces were weaned off Soviet assistance, especially the air force. The intelligence and security service, the feared KhAD was further empowered and became a fighting force in its own right. Communism and state atheism were out, capitalist reforms and a new religious public discourse were in. A new policy of National Reconciliation reached out to various religious groups, militias, political networks. The Soviet Union wanted an independent, neutral, friendly but non-aligned Afghanistan. In the international sphere, the Soviets asked the UN to provide a table where the Kabul government, Pakistan, the United States and the Soviet Union could negotiate. Crucially the Mujhadedin organizations were not invited to the talks, but this was still better than the privatized talks between the US envoy Khalilzad and the Taliban in Doha that excluded and weakened the supposed US ally in Kabul. The withdrawal agreement was reached and signed in the spring of 1988. It was far from perfect. To start with it was not a comprehensive peace agreement, it did not contain language about the coordinated decrease of military assistance to the Muj (something that Pakistan and the US vehemently opposed to the end). But the Geneva accords contained a deadline for the exit of the Soviet troops. The execution was far from perfect, but the last Soviet soldier, General Gromov himself, crossed the Friendship Bridge on the Amu river on February 15th, 1989 as scheduled. CIA analysts forecast that the Muj will take Kabul within three months. But government forces and their allied militias pushed back the Muj assault on Jalalabad in March 1989 and stabilized the front. At a fraction of the cost of maintaining the 40th Army in Afghanistan, Moscow stayed behind its ally, regularly supplying Kabul forces with fuel, ammunition, spare parts and specialised technicians for systems maintenance. Najibullah’s knack for alliance building made the rest and his regime survived three years. Once the Soviet Union imploded and Yeltsin decided to cut aid to Kabul at the beginning of 1992, the Communist regime was doomed. Without cash to oil the alliance with the governmental side, the Dostum’s militia switched sides and the Muj occupied Kabul on the 28th of April 1992.

Caveat: no one is nostalgic for the superpower of old. The Soviets had set a very low bar in Afghanistan, a country on which they wrought unspeakable destruction and suffering. So it is telling that the United States and NATO exit was worse – strategically and toward their ally – than the totalitarian cumbersome Soviet juggernaut.

Afghanistan as an empty space

This seemingly structural inability in assuming the right point of view – and by 'right' I do not necessarily mean in a moral sense, but able to develop sound knowledge instead of phony regurgitations – was captured early on by the American academic Marc Herold. A professor of economics at the University of New Hampshire in Durham, N.H., Herold was the first to document systematically how Afghan civilians were dying by the thousands under the bombings that sagged the Taliban resistance in the Fall of 2001. And he continued keeping this tragic tally until the UN mission to Afghanistan eventually noticed around 2007 that the war had not really ended and Afghans were being killed at alarming rates and started collecting data about them.

Besides his systematic compilation of war-related fatalities, in 2006 Dr Herold authored an essay on how Afghanistan was conceived in American strategic planning as an essentially “empty space” to be filled with a projection of power. An empty space to serve as a testing ground for new weapon systems and tactics. The “battleground tested” label adds value in the global weapons market. The concept remained relevant even after Herold's essay, in other domains.

An empty space bombarded with reports: alongside stratofortresses and drones, think-tanks are as important for another kind of bombing. The empty space has to be filled with words, narratives. Local knowledge is precisely labelled as such, a subordinated subcategory.

The discursive bombing creates an epistemic wasteland where the foreign “country expert” thrives. This is actually one of the telltale indicators of national misery. More than GDP per capita and hospital beds, a child knows that she is in trouble if she’s born into a place with country experts. Anyone peddling themselves as “France experts” would be ridiculed as a deluded mountebank, at best. But “Afghanistan experts” have been thriving for decades.

An empty space filled with hobbies: in a more subtle way, Afghanistan was conceived as an empty space also in the imagination of do-gooders from all over the world. Decent fellows realised that they could project their hobbies and idiosyncrasies and turn them into development projects on a giant silver-screen never short of funding.

This is how a whole aesthetic of decontextualized banality took hold. Western reporting amplified the excitement: “Wow! Now there is X in Kabul!” Where X could be any trivial Western suburban pursuit from salsa classes to skateboarding. Perhaps innocent in themselves, these were often branded as successful metrics of the development of a “vibrant” civil society.

Finally, an empty space filled with words: Afghanistan was swamped with a foreign discursive overproduction that represented them from outside-in. An army of young, brilliant fixers and translators made most foreigners feel utterly comfortable in their native English, without bothering to learn the “native” language. Meanwhile, the linguistic NGO-isms installed themselves in the everyday parlance of the new generation, harbingers of a deeper transformation.

In due course the new Afghan generation recovered their own voice and took on the many foreign experts who overstayed their welcome. I trust their strength and confidence will assist them in facing a new, formidable enemy.

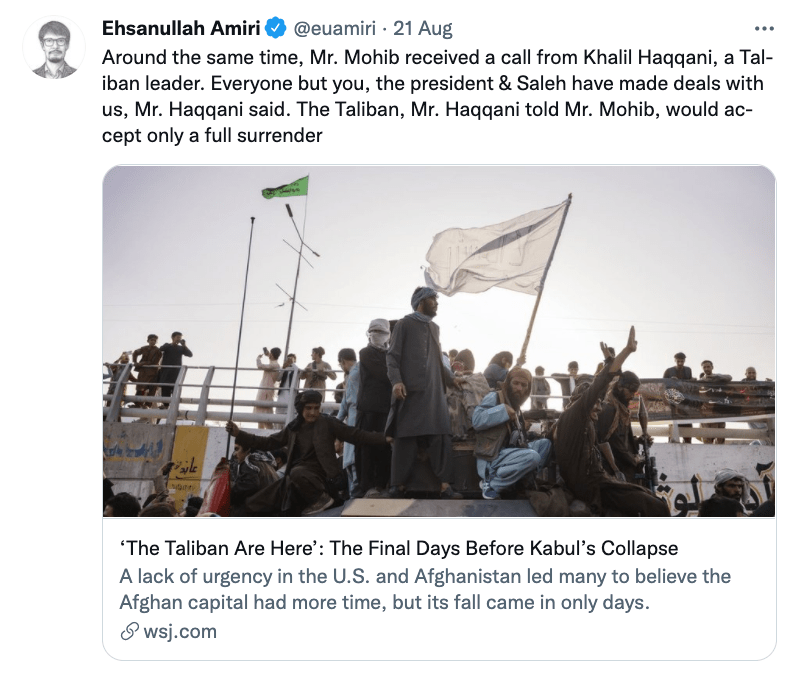

Cover photo: Taliban fighters enter Kabul, 15-16 August 2021. (C) Reuters.