On the night of April 24th, 1915, executives of the Ottoman Young Turks-led government emitted an ordinance giving way to the 20th century’s first genocide: the killing of one million and a half Armenians (along with thousands of Assyrians other minorities). Yet, on the year marking the 105th anniversary of this tragedy, the international community persists in dealing with the Armenian question in unsettled terms, split between progressivist idealism in favor of human rights, and the legacy of those same sovereign principles which have allowed for the diffusion of European nationalisms.

The ordinance, which called for the arrest of intellectuals, politicians and other members of Armenian society’s elite, was the direct result of the nationalist and autonomist policies promoted by the Young Turks’ program since the beginning of the 20th century, in response to the inevitable and imminent decline of the Ottoman Empire. Indeed, since Bulgaria proclaimed its independence in 1908, through the Balkan wars of 1912 and 1913, the Young Turks party switched from a more liberal, progressivist ideology to a nationalist one. The Committee of Union and Progress, the leading party in the Ottoman Empire at the time, began implementing authoritarian policies to safeguard its last territories from the emerging provincial independence movements and all external interferences by European powers. In this context, the Adana Massacre carried out against the Armenian population in 1909 was proof of growing intolerance towards minorities by the Ottoman government.

Even if the 1915 arrest ordinance was instantly condemned in a joint declaration by France, Great Britain and Russia, which defined the massacres perpetrated by the Young Turks as “crimes […] against humanity and civilization”, WWI diverted the European countries’ attention, de facto allowing the Ottoman government to execute its mass extermination plan. The ‘temporary law of deportation’, which outlined the forced transfer of Armenians, and the subsequent ‘temporary law of expropriation and confiscation’, which ordered the seizure of Armenians’ goods and properties, were promulgated in May 1915 and constituted the turning points for the massacre of thousands of people and a resulting diaspora flow. With the European’s attention focused elsewhere, at the end of WWI hostilities, all violence and human rights violations perpetrated against the Armenian community were concealed under a blanket of silence.

Against this backdrop, the Turkish government was free to adopt a denialist approach. Since the 1923 proclamation the Republic of Turkey, it has never officially recognized the committed crimes as genocide. Au contraire, art. 301 of the Turkish Penal Code (last modified in 2005) criminalizes the exact opposite of negationism: “[…] any person who publicly denigrates Turkishness, the Republic or the Grand National Assembly of Turkey shall be sentenced to six months to three years of imprisonment”. Alongside curbing freedom of both expression and the press, the article underlines Turkey’s identitarian stance, in which negationism finds fertile ground: indeed, qualifying the 1915 facts as “genocide” is considered “denigration of Turkishness” – therefore forbidden.

Disjointing Turkey’s constitution process from the Armenian genocide would be misleading: the latter fell under the policies aimed at protecting the Turkish vatan (fatherland) and the ideology of the nation-state, both necessary elements of the newly established Republic. Turkey has therefore never recognized the Armenian genocide as a historical fact, considering it as a menace to the State’s foundations and socio-cultural principles.

Turkey’s relations with Armenia were frozen throughout the Cold War period. Right after the proclamation of Armenia’s independence in 1991, they attempted to restart, but were again paralyzed by the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan for the Nagorno-Karabakh, a region inhabited mainly by Armenians but annexed to Azerbaijan after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. At the outburst of the conflict in 1992, Turkey supported the Azerbaijani cause, closing the borders and ceasing diplomatic relations with Armenia. In the years that followed, the political rupture between the two countries was confirmed in different occasions: the failure of the Turkish-Armenian Reconciliation Commission (TARC) in 2004 due to “substantial differences”, and the defeat of the 2009 Zurich Protocols, signed but later proven ineffective by the strong opposition to the constitution of an intergovernmental Commission “with the aim to restore mutual confidence between the two nations, including an impartial and scientific examination of the historical records and archives to define existing problems and formulate recommendations”. While political relations among Turkey and Armenia remain frozen, Azerbaijan is still openly at war with Armenia and therefore adopts a negationist stance towards the genocide, also in virtue of its position as a Turkish ally.

Ankara’s position thus revealed difficulties in maintaining its ‘zero problems with neighbors’ policy in accordance with its regional supremacy objectives, especially when seen as competing with Russia for the rule. At the same time, diplomatic positions suggest that Turkey’s attitude is far from a recognition of the past wrongdoings and a reconciliatory path with Yerevan. In the past years, however, part of Turkey’s civil society has condemned the 2007 assassination of Armenian-Turkish journalist Hrant Dink, and a more positive stance has begun to appear regarding a possible reconciliation at civil society level through both Armenian and Turkish initiatives fostering better knowledge and awareness about issues concerning the two neighboring countries.

Meanwhile, the recent Armenian Republic has been dealing with its own national identity and future perspectives. After decades of corruption and misgovernment, it seems that spring 2018’s velvet revolution has taken a new direction for the country. In relation to the genocide question, current Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, the leader of the spring revolution, elected into office in May 2018, has removed from his political agenda an official recognition of the 1915 crimes as a precondition for a political normalization with Turkey. This choice has a political and economic nature rather than a moral one. As a matter of fact, since the diplomatic rupture with Turkey brought around the closure of its Western borders, and the ongoing Nagorno-Karabakh conflict maintains the Eastern borders closed, Armenia has found itself isolated and weakened within the geopolitical context of the South Caucasus.

Despite political and economic strategies, Turkey’s recognition of the perpetrated genocide would be essential in order to achieve a reconciliatory path, and an acknowledgment of the past crimes is still requested by the Armenian community around the world, especially by diaspora associations. For the latter, the recognition could put an end to the identitarian conflict which compromises their shared historical and cultural heritage, as well as allow for an answer to the century-old calls for justice, hence normalizing their diplomatic relations. As for the Turkish side, during the past years the stance towards the Armenian genocide matter has been ambivalent, switching from openness to dialogue, such as Erdogan’s decision to reopen the historical archives in 2003, to vehement opposition, like in the aforementioned cases of both TARC and Zurich Protocols, mainly due to the political and economic interests to maintain and sustain its ally, Azerbaijan, in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

In 2020, more than a century after the massacres, questions and calls for justice still stand and the international community has not managed to provide sufficient answers thus far, therefore contributing to the historical and juridical vacuum. Even though, under today’s standards, the modalities with which the massacres were perpetrated fall into the category of human rights violations, only 29 States have recognized the genocide thus far – amongst them are Argentina, Canada, and France, where most of the diaspora community is located. This underlines the complexity of the matter and proves that international criminal justice was (and still is) bound to political realism.

A key role for the resolution of the Armenian question could still lie in the activities of international organizations, both to guarantee the active participation of the Armenian diaspora, as well as to safeguard the interests of both Turkey and Armenia. The European Union could be particularly fit for the mediator’s role, with its strong regional presence and its political interests towards Turkey, which is stuck in its accession procedure to the Union for years. As a matter of fact, on occasion of the genocide’s 100th anniversary in 2015, the European Parliament (EP) adopted a resolution that invites Turkey to recognize it and “to pave the way for a genuine reconciliation between the Turkish and Armenian peoples”. Despite the EP resolution having no binding effect, it still demonstrates the EU’s attempt at safeguarding human rights, including remembrance and victims’ rights, in an attempt to reconcile the two countries. Although the recognition of the Armenian genocide could be included in the political agenda of the European External Action Service (EEAS), the EU remains very ambivalent on it, due to the migration issues in which Turkey has the upper hand – as well as fearing the political retaliation that a clear stance regarding the Armenian genocide could provoke in its relationship with Ankara.

To reach recognition objectives, the numerous initiatives and lobbying campaigns promoted by the Armenian diaspora in Europe and the United States remain fundamental in highlighting the complexities of the Armenian question, as will be denouncing the Turkish nonrecognition and the international community’s silence. The perception of the Armenian genocide amongst Armenians living in the country and diaspora ones, while remaining an important instance for both, has a different impact on each. On the one hand, Armenians currently living in Armenia perceive Turkey’s alliance with Azerbaijan as a bigger obstacle to reconciliation than the recognition of the genocide, as they are more concerned with the current political and economic situation and would rather seek talks to establish stability in the South Caucasus region; amongst these feelings is nestled PM Pashinyan’s more “accommodating” strategy, which is still very cautious, given the historical and ideological circumstances. On the other hand, diaspora Armenians consider the recognition as an essential precondition to any agreement with Turkey: therefore, these movements are not limited to a call for justice for the victims, but also request closure – as a direct descendant of the Armenian diaspora, I will never be able to stress this enough – for the trauma and grief still permeating the Armenian identity to-date, irrespective of the years passed.

Acknowledgements

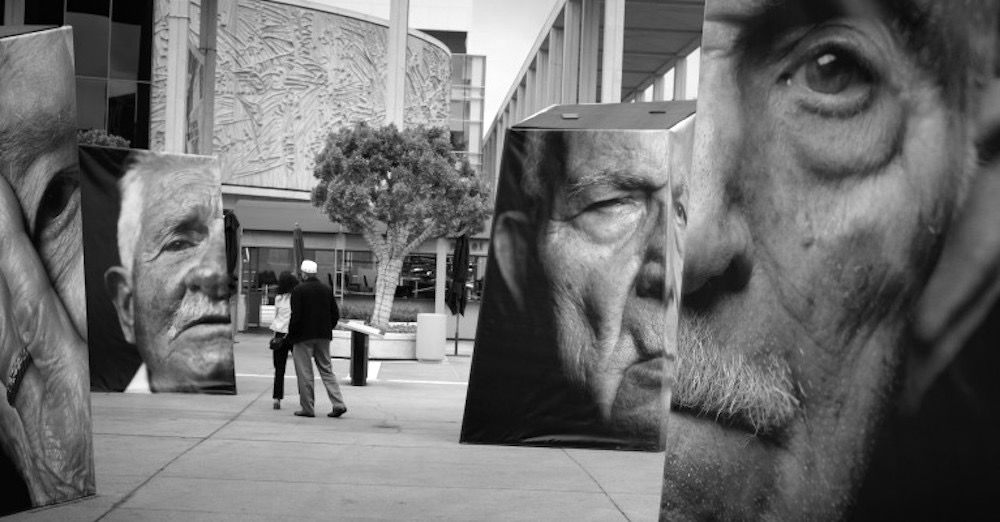

Cover photo: "visitors view an outdoor installation called iwitness, a grouping of 20 larger-than-life 3D photo sculptures of Armenians survivors, at the Music Center Plaza in downtown Los Angeles on Friday, April 24, 2015. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)"